Labor & Economy

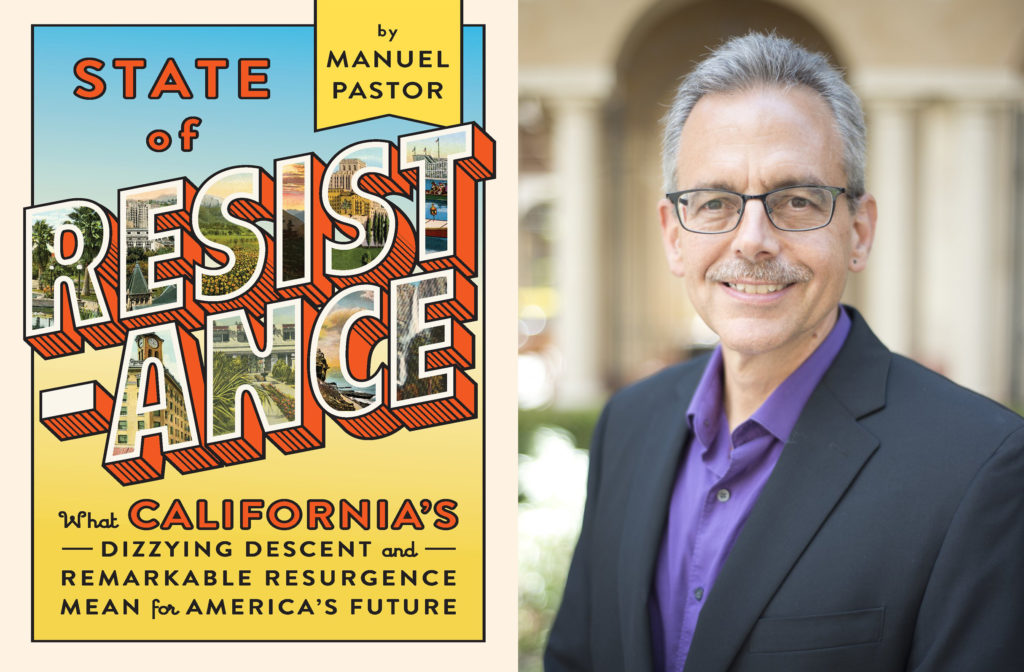

Manuel Pastor on California’s Golden Resistance

A new book argues that the dismantling of policy initiatives that made up the Golden State’s successful postwar social compact were, in part, driven by racial fears as state demographics shifted.

When reading Manuel Pastor’s State of Resistance, it’s hard not to wonder if the present White House dumpster fire is being fed by the same ideological tinder that fueled California’s political right wing from the 1970s throughout the 1990s. Pastor, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California, offers an unsentimental view of that period: “By the 1990s racism had really gotten the better of us. Race made us take our eye off the ball of development.” His book, subtitled, What California’s Dizzying Descent and Remarkable Resurgence Mean for America’s Future, recalls that two-decade span as a disaster for California’s development as a forward-looking state, but also, perhaps, as a necessary prelude to its current status as the progressive movement’s shield against the Trump administration.

A community activist, contemplating the destruction visited upon Los Angeles after its 1992 civil unrest, is quoted as wearily declaring, “There’s an immediate need to think long-term.” In Pastor’s view it is long-term thinking that has carried California forward as the model of a state of resistance—as a leader in wage justice, in climate change policy, in support of immigrant and other civil rights.

Pastor’s book also examines what has led to the Golden State’s periodic explosions. He takes readers at a brisk pace through 20th-century California history: years when migrants from across America came to it in hopes of bettering their lives; through various political backlashes and then onward to the social movements that learned to build and wield power and helped turn the state in a progressive direction.

In his book and during a recent interview, he is clear about the ways in which the playing field in the state was never quite level for people of color but, until the 1990s, had at least been seen by a broad spectrum of people as a place of opportunity.

That minimal social compact, he says, was undone “by a series of well-organized and often grassroots right-wing movements usually taking advantage of the racialized anxieties of voters frightened of a changing state.” Pastor argues that the dismantling of policy initiatives that made up the Golden State’s successful social compact—support for public education, transportation, housing desegregation and economic development–were in part driven by racial fears as state demographics shifted.

One pivotal moment came in 1978, with the passage of Proposition 13, a ballot initiative ostensibly proposed to put a brake on California’s spiraling home property taxes, but which the author claims defined a racial and generational divide. The new law had the practical effect of protecting older, whiter homeowners from rising property taxes and locked in commercial taxes at artificially low levels for decades — while ultimately stripping funding from state services that support the young, especially education and public infrastructure.

But, as California turned younger and browner, conservatives were only getting started, as they pushed through a wave of ballot initiatives to recalibrate the social compact and target people of color:

- Proposition 187 in 1994 sought to block undocumented immigrants from access to education and non-emergency health care and elections; it succeeded at the ballot box but those two features were overturned in court;

- Proposition 184, a 1994 three-strikes law, imposed a life sentence for any crime if the offender had two prior convictions categorized as serious or violent, and disproportionately affected black youth;

- Proposition 209, an anti-affirmative action measure passed in 1996, inhibited access to higher education for people of color.

Pastor outlines vibrant grassroots efforts that emerged in Los Angeles in response to the civil unrest and the public policy that fueled it —the South Los Angeles organization SCOPE, committed to power-building in poor and black and Latino communities; the Community Coalition, founded by now-Congresswoman Karen Bass; the economic justice-inspired Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy and others that connected with similar organizations throughout the state.

“Relationships got built so that when people were pursuing slightly different strategies they didn’t end up with a permanent hostility,” Pastor says. “They just recognized that they were pursuing different strategies at different times.”

By the 2016 elections the organized right wing had seized powerful pieces of the national narrative, according to Pastor. “The Tea Party was astroturfed in by the Koch brothers–but actually did have a grassroots component and spoke to a high level of pain and anger that was out there.”

Social change means being attentive to narrative—how people talk with one another, Pastor says. “How do you change the debate so that it’s not, ‘We need to raise the minimum wage,’ it’s the Fight for Fifteen? That it’s not about ‘comprehensive immigration reform,’ it’s about Dreamers? That it’s not about ‘civil rights for gays,’ it’s about marriage equality?”

Crucial to making California a state of resistance was a turn from the conventional get-out-the-vote approach that pops up every election season and does little to connect with the electorate.

“What happened in California was this emergence of integrated voter engagement—what we call community organizing-based politics,” Pastor says. By this he means cultivating new and occasional voters, rather than those who never miss an election and tend to vote conservatively. The book details the work of California Calls, a statewide network of community organizations located in towns from the Central Valley to San Diego County, whose members work door-to-door between elections to stay in touch with the political pulse of voters and mobilize them at election time, boosting the turnout from low-income areas.

Throughout the country there are similar efforts that Pastor calls “movements that capture the imagination,” including the New Florida Majority, focused on mobilizing and including marginalized communities, and Black PAC, which provided a vote margin to turn an Alabama election for a U.S. Senate seat against hardline conservative Roy Moore.

“Political change is not just about elections,” Pastor cautions. “We have to invest in progressive infrastructure.”

In each election season, he says, “there’s a lot of money being spent on pollsters [and] strategists who don’t produce messaging that resonates, get-out-the-vote that’s not integrated voter engagement.”

The most effective way to not get a Trump elected, Pastor argues, is to invest in the grassroots.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026Keeping People With Their Pets Can Help L.A.’s Housing Crisis — and Mental Health

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026When Insurance Says No, Children Pay the Price

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks