Black Infant Mortality: The Deadly Divide

Los Angeles County Struggling to Shrink Black Infant Death Rate

A pledge to sharply reduce infant mortality by 2023 faces daunting obstacles.

Early in 2018, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health announced an ambitious health care goal for 2023: Cut the gap between Black and white infant mortality in L.A. County by 30%.

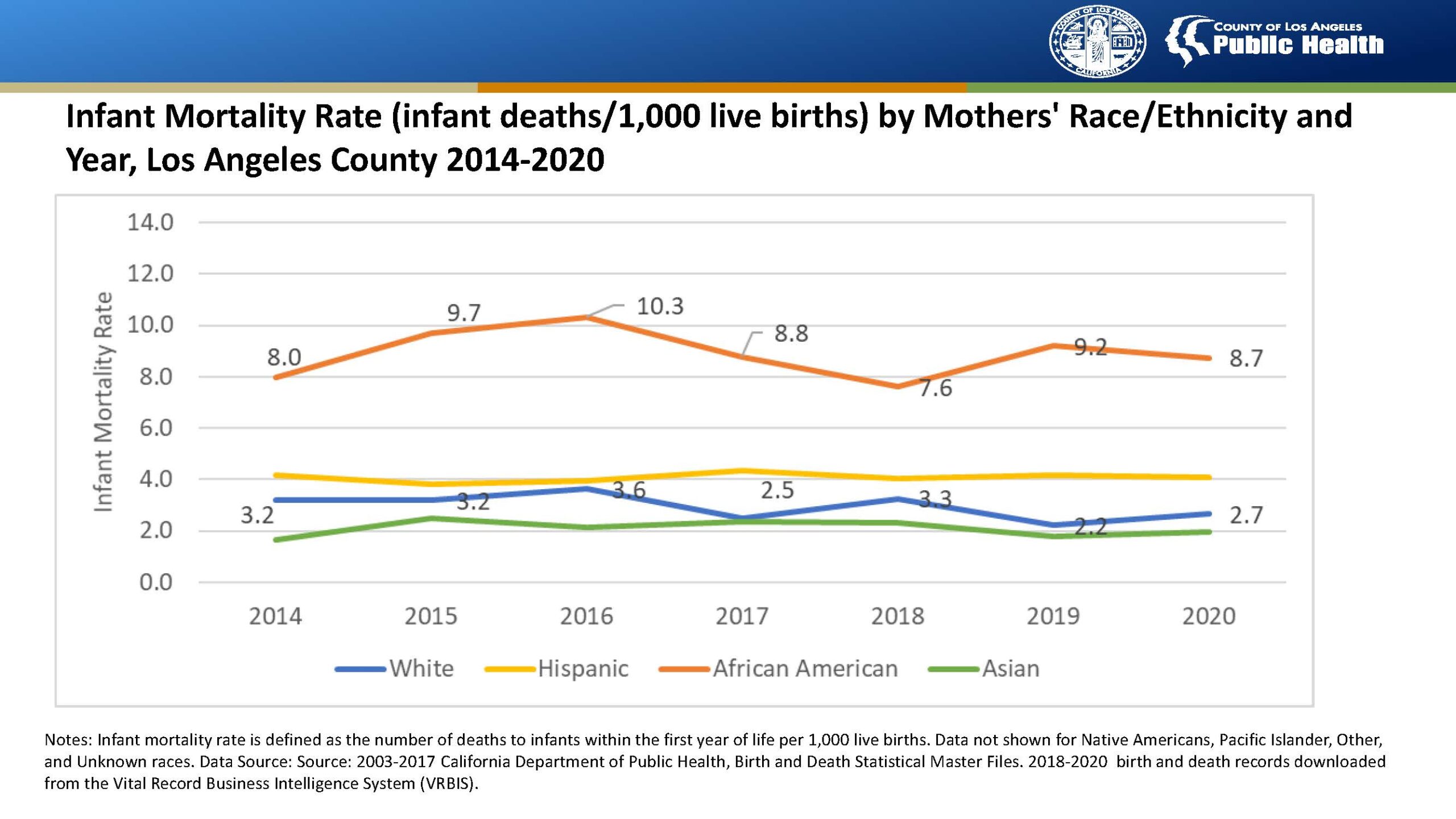

For decades, Black babies in L.A. County were dying at a significantly higher rate than white babies, primarily because they were born too early or too small.

A new effort was spearheaded by the director of the county public health department, Barbara Ferrer. Her work as executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission had been heralded as instrumental in driving a significant decline in that area’s Black infant mortality rate. She issued a similar challenge for Los Angeles, the most populous county in the nation at more than 10 million residents.

“Let’s be accountable for actually changing the outcomes, not just talking about it,” said Ferrer, in a 2018 interview about her department’s new five year program, coined the African American Infant and Maternal Mortality (AAIMM) Initiative.

Now, more than four years later, the county has not meaningfully moved that needle. According to the most recent publicly available data, the Black and white infant mortality gap remains at its prior levels despite a one-year drop in 2018.

Deborah Allen, deputy director of the L.A. County health department, strikes a confident note despite the lack of progress toward the 2023 goal. “We’re just at the point where the interventions we’ve designed as our way to operationalize the strategy we laid out is really taking hold,” she says.

But Los Angeles County Supervisor Holly Mitchell, one of the five elected officials who have ultimate authority over county departments, said, “We have not turned the corner in really changing the trajectory of these data points. They have been the same for several decades,” she said. “That’s a problem.”

In conversations with more than 30 mothers, health officials, nurses, doulas, academic experts and community advocates, many stressed several key areas where the state and county must improve beyond the current reach of the AAIMM initiative. This includes filling gaps in vital services, improving regional health care access, and broadening efforts to meaningfully shift hardened racial biases among health care professionals.

Charts by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

* * *

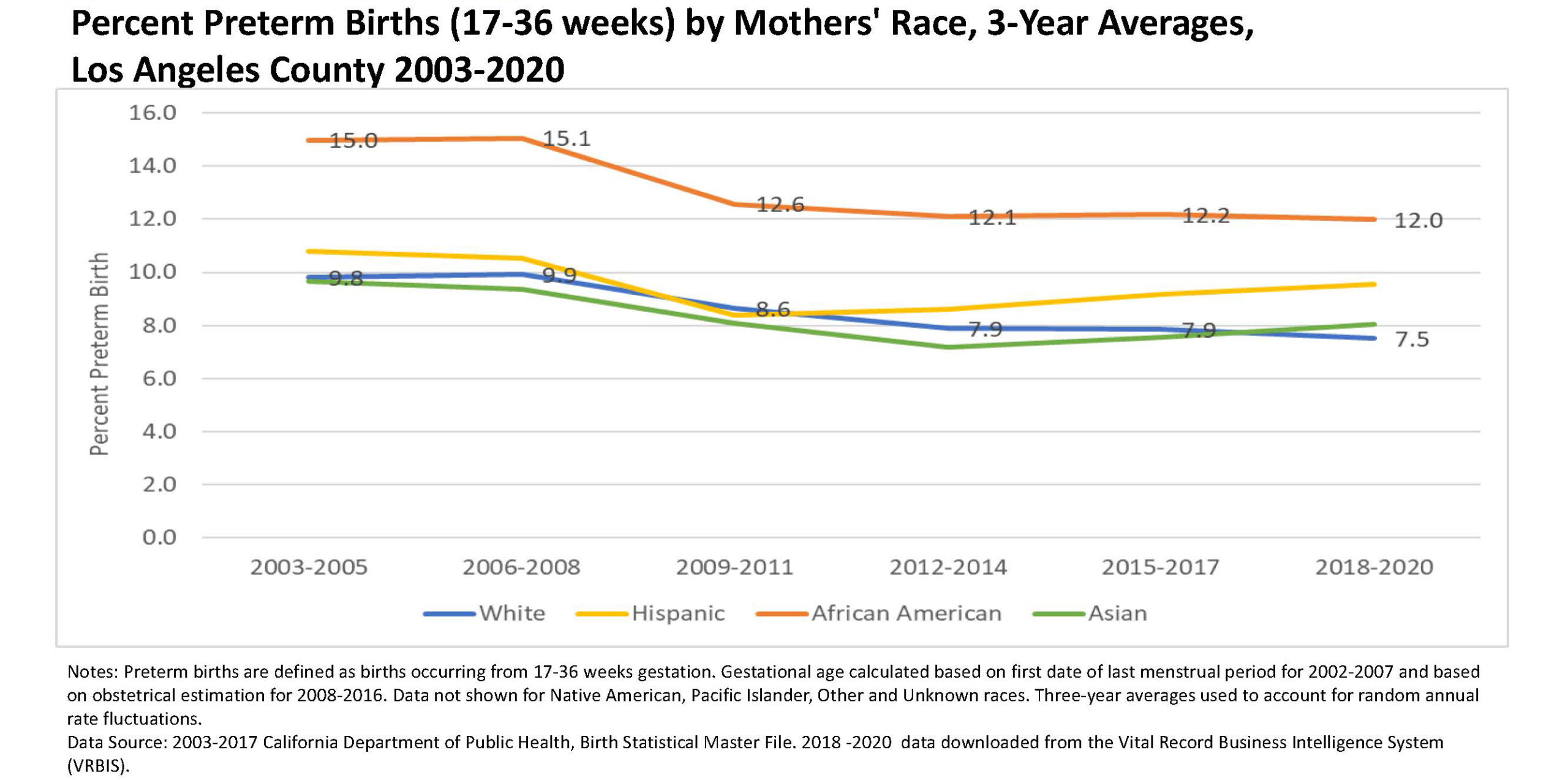

Infant mortality is defined as the death of a baby before their first birthday. Causes include premature births, extremely low weight at birth, fetal malnutrition and congenital abnormalities. In L.A. County, Black babies are nearly twice as likely to be born prematurely than white babies, and more than twice as likely to be born too small, under 2,500 grams.

Though behavioral and socioeconomic factors can have a profound impact on a baby’s health, at the end of the day, Black women with private health care suffer worse health outcomes than white women with public insurance, for example. White mothers who flunk high school enjoy better health outcomes than better educated Black mothers. It all boils down, say experts, to the cumulative stressors from racial discrimination the Black community routinely faces, permeating every aspect of life.

A key term is “weathering,” coined decades ago by public health researcher Arline Geronimus to describe the body’s response to stressful situations, and the wash of stress-triggered hormones like cortisol. Over time, these hormones monopolize the energy the human system should be putting into fostering healthy pregnancies, weathering the body and predisposing Black women to chronic conditions like hypertension, gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. These impacts can harm birth outcomes and span generations.

For Black mothers, the stress of pregnancy and childbirth is exacerbated by racial biases baked into the health care system.

“High infant mortality, or high preterm birth, is a continuum over a 400-year period,” says Wenonah Valentine, founder and executive director of iDREAM for Racial Health Equity, a leadership, training and advocacy network.

For Black mothers, the stress of pregnancy and childbirth is exacerbated by racial biases baked into the health care system. Studies have found that physicians are significantly more likely to underestimate pain in Black patients compared to other racial groups. In L.A. County, Black mothers have been warning for years about the treatment they receive in hospitals and clinics. The husband of a Black woman who bled to death hours after childbirth in 2016 recently sued Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in L.A., alleging she died because of inadequate care fostered by a culture of racism at the hospital.

The suit was subsequently settled out of court. A Cedars-Sinai spokesperson wrote in an email that they were unable to provide any details of that settlement, but added that “while disparities exist throughout our society, we are actively working to advance equity in healthcare. We commend [plaintiff] Mr. Johnson for the attention he has brought to the important issue of racial disparities in maternal outcomes.”

Which is where the AAIMM initiative — a collaborative effort among local and state health departments, nonprofits, health care providers and community organizations — steps in, building as it does upon the county’s existing infant and maternal health programs. The initiative includes expanded access to doula care, free home visits to Black families and breastfeeding education and support for Black mothers, among a slew of other services.

The AAIMM initiative has coincided with other statewide efforts to address the problem, like the California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act, mandating implicit bias training for all perinatal health care professionals working in the state. The first such program in the country, the law went into effect at the start of 2020, but compliance rates are still unknown.

Last August, the California attorney general issued a letter to perinatal care providers, giving them until the following Sept. 20 to provide compliance information. One year on, the attorney general’s office is still processing the data. “We anticipate being able to provide more once the data has been reviewed and analyzed by our staff,” wrote a spokesperson in an email.

Advocates point out that the program — an hourlong online training session — should be just a starting point. According to Valentine, deeper training in “cultural humility” is needed to really shift attitudes among health care workers. “That means you’re looking beyond yourself,” she says. “You’re looking at the person, the family, the support person, and you are looking at the baby and who they are, and how to serve them.”

A key barrier to increased doula care in Los Angeles County is state reimbursements rates.

There are other ways to improve the Black birthing experience in L.A. County, such as increasing Black representation within the health care ranks and among pre- and perinatal providers. Newly born Black babies are significantly less likely to die when they’re cared for by Black physicians, for example. Doula care also improves the likelihood of a healthy birth, and under the AAIMM initiative, the county has increased the number of Black doulas providing free care in certain parts of L.A. County. But their numbers — a cohort of 12, supplemented by other doula programs in the area — still don’t nearly address the need.

Jessica Wade, a doula in the Antelope Valley as well as manager of Maternal & Infant Health Initiatives for San Diego with March of Dimes, a nationwide nonprofit focusing on infant and maternal health, says she is one of just a handful of Black doulas in the entire Antelope Valley. “There needs to be double or triple that, at least,” she says, for a region of more than half a million.

A key barrier to increased doula care in L.A. County is state reimbursements rates. More than 50% of prenatal care for the county’s Black community is covered by Medi-Cal, and last year’s California Momnibus Act paves the way for the state to now reimburse doulas at a rate of $1,154 per birth through Medi-Cal. But the typical cost of doula care can stretch as high as $3,000 per patient in California. For Black families most in need of this help, the remaining amount is often way too much, says Wade.

Cherished Futures for Black Moms and Babies, another organization working with the AAIMM initiative, offers two-year programs to help hospitals identify and then fix institutional racial blindspots to improve their quality of care to Black families. During this work, Cherished Futures has found that some hospitals have had to address their treatment of Black health care workers as well, says Asaiah Harville, the organization’s birth equity coordinator.

“For one of our cohort hospitals, they actually had to do a whole internal shift. ‘Wait a minute, we have to address what’s happening within our own walls with staff even before we can address how we change our interactions between patient and provider,’” Harville says. She describes common feedback from Black health care workers — feelings of being ignored and dismissed by hospital colleagues and superiors — as mirroring the sorts of remarks routinely heard from Black mothers and families.

* * *

Los Angeles County’s 10 million residents are spread out across more than 4,700 square miles — an area bigger than Delaware, with a population larger than North Carolina. As such, the county health department breaks the region into eight Service Provider Areas. Each region presents a different set of obstacles to navigate — from access to health care to limited transportation to basic economic needs of the residents — as the county decides how to distribute its resources.

AAIMM has focused its funds and resources on the Antelope Valley, South L.A. and the South Bay, regions that have historically experienced the highest Black infant mortality rates. But even in these areas, there’s still much work to do.

In the Antelope Valley, which sprawls over 2,200 square miles of scattered communities, experts describe a region struggling to hire and then retain trained health care workers.

The housing crisis has disproportionately impacted African Americans, who account for 30% of all the unhoused in L.A. County, but are 9% of the overall population.

Both Lancaster and Palmdale are designated primary care shortage areas for their low provider-to-patient ratios and high number of residents living below the poverty level. Wade calls the valley a “maternity care desert.”

“For the needs of our community, our social determinants, health outcomes, we need a lot more resources,” says Michelle Fluke, executive director for the Antelope Valley Partners for Health, a health advocacy program. Until last year when the Palmdale Regional Medical Center opened its doors to deliveries, the Antelope Valley Medical Center in Lancaster was the only birthing hospital for the entire valley, for example.

The onset of COVID-19 appears to have also blunted the initiative’s impact in the Antelope Valley. Attendance at the valley’s regular AAIMM Community Action Team meetings has shrunk significantly since the pandemic, says McKinley Kemp, AVHP program director, and he describes the last few years as an “uphill struggle.” This has led Kemp to go before the Palmdale City Council and ask for more support.

Chart by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the neighboring San Fernando Valley, the Black infant mortality rate is relatively low for L.A. County, but the rates at which Black babies there are born too early and underweight are still worryingly high, which is why community health advocates lament the 2016 loss of the Valley’s Black Infant Health program — a state funded backbone of California’s approach to improving Black health outcomes — due to funding cuts.

“The part that keeps me up at night is that for the years the program hasn’t been in place, how many lives did we miss touching? Thousands upon thousands,” says Jessica Sullivan, executive director of the African American Leadership Organization, a San Fernando Valley nonprofit, who argues that the services offered through AAIMM haven’t yet replaced what was lost.

Some problems transcend regional differences across L.A. County. The housing crisis has disproportionately impacted African Americans, who account for 30% of all the unhoused in the county, but are 9% of the overall population.

“What’s the point of passing policy if it doesn’t get to the community?”

~ Janette Robinson Flint, executive director, Black Women for Wellness

Veronica Lewis is the director of the Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System, a South L.A.-based nonprofit that connects homeless and low income individuals with services. “Over the last five years, we’ve had three to four babies die,” says Lewis, highlighting the death of Black babies that occurred after their mothers had been placed into interim housing by the organization. “Even recently, we had a 2-month-old pass away,” she adds.

But it’s unclear if and how Black infant mortality rates in L.A. County have been impacted by rising homelessness.

According to Deborah Allen’s rough estimations, approximately 1,000 women a year in L.A. are homeless at the time they are giving birth. But the county public health department doesn’t keep an accurate record of the overlap between infant deaths and homelessness due to the difficulties in doing so, she says. “You may have been homeless part of your pregnancy. You may have been homeless all of your pregnancy. Homeless may mean you’re on the street, you’re in a shelter, or on somebody’s couch,” she says.

* * *

Many Black mothers, health care professionals and community advocates at the front lines say the AAIMM initiative has achieved what had not been achieved before: sustaining prolonged attention on a crisis in the Black community that had been largely neglected by officials. Events like Black Maternal Health Week have quickly become a staple of the county’s outreach efforts, for example. “The fact that this work has gained legs and momentum is what gives me the greatest hope for it in the future,” says Melissa Franklin, who co-leads the AAIMM initiative.

Janette Robinson Flint, executive director for South L.A. based nonprofit Black Women for Wellness, similarly champions many of the steps taken both across California and locally to help Black mothers in L.A. County. But on its own that’s not enough. “What’s the point of passing policy if it doesn’t get to the community?” she says, urging greater awareness of the available aid and services among the families that most need them.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is one of the key causes of Black infant death in L.A. County, and breastfeeding has been proven to reduce the risk of SIDS. But only 20% of Black women in L.A. County exclusively breastfeed, a number that has nearly halved since 2014. “So many moms still don’t know about us,” says Nicole Craig, a mother of four and a self-described CinnaMom — a member of an AAIMM-affiliated breastfeeding advocacy group.

Then comes the matter of money. Various federal, state and county grants and philanthropic funding sources underpin the AAIMM initiative. And while the county health department’s budget for the initiative is set to increase to an annual $3.2 million, not all funding sources are set in stone. Several key AAIMM programs are endowed with one-time grants and state appropriations, for example. First 5 LA is a major donor to the AAIMM initiative, but its coffers are built upon tobacco tax revenues, which have shrunk by 50%, which is why the organization recently appointed a strategic consultant to look for other longer-term funding options.

“We’re not at a point where we can say, quote, ‘A lot of money has been invested in this problem.’ It simply has not,” says County Supervisor Holly Mitchell. “Not when you consider the magnitude of the problem. And that’s when we get to racism. You have to stop and ask yourself: If another group of people were experiencing death at that higher rate, what would the response be?”

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Impact Fund.

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care