Coronavirus

Limited Protections Leave Tenants Vulnerable to Evictions

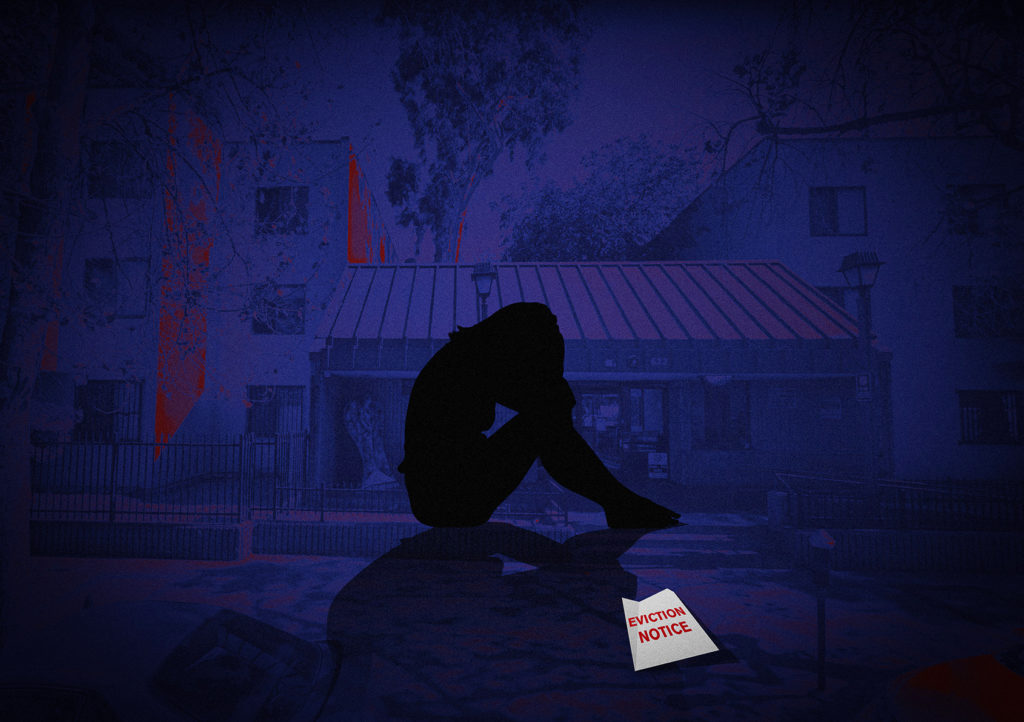

Even as Californians are ordered to shelter in place, renters face the prospect of homelessness.

Corri Hardy has been crying every day lately. For 18 years she worked as a playground supervisor at Eshelman Avenue Elementary School in Lomita before being hospitalized last August with blood clots on her lungs. Diagnosed with lupus, Hardy, 42, lost her job and then fell months behind on the $469 rent for her subsidized single apartment on Los Angeles’ Skid Row. On March 12 – three days before much of the city shut down in order to slow the spread of the coronavirus – she was locked out of her home – one of thousands of renters for whom California’s newly enacted tenant protections have proven meaningless.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has urged California cities to protect tenants who face eviction during the COVID-19 outbreak. Los Angeles is among those that has brought some relief to them, along with San Francisco, San Jose and Fresno. These and other, smaller municipalities have said that those who are ill, have lost work or who are caring for children during the current state of emergency can’t be evicted for nonpayment of rent. But housing activists say these tenant protections may be too little in some jurisdictions and too late for people like Hardy, whose apartment was located in a supportive housing complex for elderly disabled and formerly homeless individuals. The complex, called the Ballington, is owned and managed by the faith-based Volunteers of America, whose website says it is “committed to serving people in need, strengthening families and building communities.”

Housing Now, a coalition of more than 100 California organizations, urged Gov. Newsom in a March 20 open letter to enact sweeping statewide tenant protections that could help vulnerable people such as Hardy, whose autoimmune disorder makes her more susceptible to infections like COVID-19. The groups call for a ban on evictions and foreclosures, emergency rental and mortgage assistance for renters and homeowners, a suspension on mortgage payments for landlords and homeowners, and on rents for their tenants. The coalition further demands a moratorium on sweeps of homeless encampments, and the towing of vehicles where people live, as well as an end to all utility shut-offs.

So far Gov. Newsom has not acceded to the coalition’s demands. The activists are critical of Newsom’s March 16 executive order, which remains in effect until at least May 31, in which he allowed California cities to offer relief for both residential and commercial tenants but issued no statewide orders. In a March 25 virtual news conference, the governor noted his concern about what cities are doing or failing to do: “If we don’t see things materialize, we reserve the right to look at a state overlay.” But Newsom added that the legal issues involved in doing so “are more complicated than they appear.”

On March 23, however, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti temporarily suspended until June 19 all evictions by landlords who wish to remove their rent-controlled units from the market under the terms of California’s Ellis Act. Santa Monica has also suspended Ellis evictions. Such evictions have been on the rise in many gentrifying communities in Los Angeles and around the state because landlords earn more by selling, or by demolishing and rebuilding their property in hot real estate markets, than by collecting rent on rent-controlled buildings. In L.A. alone last year, more than 1,600 rent-controlled units were removed from the market, and their tenants evicted.

* * *

Volunteers of America learned Hardy was ill in January when her doctors informed them, said the organization’s spokesman, Orlando Ward. But the organization proceeded with her eviction anyway. On March 12, building managers told Hardy she could enter her apartment only to gather important papers. Four days later, L.A. County sheriff’s deputies installed a lock-out device on her door.

Ward said the VOA, which also manages two other supportive housing complexes in Los Angeles, doesn’t have an explicit eviction policy for its elderly, disabled and formerly homeless clients, but said eviction is a last resort. Still, he said the organization discontinued her tenancy in part because Hardy had repeatedly demonstrated an inability to pay rent.

“We are trying to help people stay housed. We also have to think of other folks,” Ward said. “[She’s] not paying for this high-demand, low-income unit. We have a waiting list and people who are literally dying on the street trying to get in.”

Now, as public health officials warn Angelenos to stay home, Hardy doesn’t know if she’ll have a safe place to hunker down and wait out the contagion. The VOA offered Hardy a bed in one of its homeless shelters, but she opted to stay with her sister, an arrangement that is temporary.

For Silver Lake tenant Chris Springer, a freelance artist whose work offers have dried up in the current crisis, the possibility of having more time to pay rent provides much needed relief. But the temporary bar on Ellis Act evictions will allow her to breathe far more easily.

“I hustle a whole gamut of art,” the 49-year-old Springer said. A tall, glib woman with a striking splash of blue in her dark hair, Springer also styles hair and does home décor. But with the need to stay away from others to avoid infection, work is already growing scarce. What’s more, Springer’s bartender roommate has been laid off and is applying for unemployment benefits.

“I already live on the edge,” Springer said. “With everybody I know, 70 percent of their paycheck goes for rent.”

Her landlord is seeking to sell her unit and two others in the building to create a condo-like arrangement known as tenants in common. Springer is set to appear in court this May to fight the eviction because, she said, she and her neighbors don’t want to leave their community – and can’t afford an L.A. apartment, especially anywhere near Silver Lake.

“It’s a relief for a lot of people I know,” she said of Garcetti’s executive order. “Let’s see how long it stays in effect.”

* * *

But tenant attorney Elena Popp, who heads the L.A.-based nonprofit Eviction Defense Network, claims the city of Los Angeles’ renter safeguards aren’t protective enough.

“While we are pleased these are steps in the right direction, it does not go far enough and continues to kick the can down the road,” Popp said.

The city’s measures don’t ban evictions; they simply provide a defense in case tenants are evicted for nonpayment of rent, Popp said. Furthermore, when the state of emergency is lifted, tenants will have only six months to pay their landlords back rent – at a time when many will have lost work and will be financially stretched.

“There is not enough to make up that gap in a six- or 12-month period, so we need permanent rent forgiveness,” Popp noted, adding that the mayor’s executive order only delays Ellis evictions until June – by which time it will be difficult for tenants to find new housing after a potentially long period of unemployment.

Popp said she and other housing advocates are not at the table when Mayor Garcetti and others make decisions about rent relief, but that they should be, adding that now is the time for tenants to get involved in advocating for themselves.

Meanwhile, Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) has introduced Assembly Bill 828, which would bar COVID-19-related evictions during the state of emergency and for 15 days thereafter. Ting’s bill, which offers more protection than many cities have, would allow renters to remain in their homes as they catch up with rent payment under court-approved repayment plans that could be extended until March 2021.

The California Apartment Association said on its website that any eviction bans be “carefully tailored” and “should clearly state that rent is not waived but merely delayed.”

Corri Hardy, the former VOA tenant, is currently seeking help from other homeless services organizations to find housing.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, an organization created by the city and county to coordinate housing and services for the homeless, and which funds supportive housing organizations, including the VOA, did not return Capital & Main’s phone calls about any guidance on evictions it has provided to its partner organizations.

Meanwhile, Hardy said it is difficult to follow her doctors’ orders to minimize worry, eat well, get enough rest and stay in a clean environment as she struggles to maintain a roof over her head.

“I’m stressing out over this,” she said. “The things that are going on with me are making me sick.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts