Latest News

The Geography of Despair: Homeless Deaths Are L.A.’s Other Epidemic

They died in parking lots, in hospitals, in train stations and in encampments. Now the county’s homeless must face the coronavirus.

More than 1,000 people without homes died in 2019 in Los Angeles County, a sprawling, 4,751-square-mile region whose homeless population has mushroomed in recent years as housing has become increasingly unaffordable.

They died in parking lots, in hospitals, on train station platforms and in encampments. They were still in their teens and well into their 80s. Some died violently of gunshot wounds or a hit-and-run, while many quietly passed away from natural causes or of a drug overdose. Black people suffer rates of homelessness that are about four times higher than their share of the county’s population, and consequently are vastly overrepresented among those who die unhoused.

How to Use These Maps

Capital & Main mapped each homeless individual’s death with data provided by the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s Office. One red square on the larger map represents an individual death. To view information about each person, including their age, gender and where and how they died, click on the square. Zoom into the map with the controllers on the left to see where they died or type in the name of a city to zoom into that area. In the last map, click on the bar or use the dropdown list to navigate to a mapping of deaths per year. Use the toolbar on the left to zoom in or out of the map.

Maps created by Joanne Kim

This year, the county’s homeless — who are aging and far sicker than the population at large — face an additional existential threat: the coronavirus, an infectious disease that can be warded off only with frequent hand washing and social distancing, both of which are difficult for those without homes.

To comprehend this unfolding tragedy’s scope, Capital & Main has mapped the location of all of 2019’s known deaths. Our analysis relies on the L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s Office mortality count, a partial list that includes only those deaths that were investigated by that office. The number of homeless deaths reported — 1,039 — represents a 13 percent increase over the prior year and roughly tracks with the rate of increase in homelessness in 2019.

* * *

Later this year the L.A. County Department of Public Health will release a full count of homeless deaths, which is expected to be higher than the coroner’s. On June 12, county officials reported a 12.7 percent rise in homelessness over last year’s point-in-time count, an increase that predates the impact of the COVID pandemic and that brings the total number of homeless people in the county to 66,433.

In 2019, the leading cause of death for homeless people in Los Angeles County was drug and alcohol overdose, according to Capital & Main’s analysis of deaths investigated by the coroner’s office. Such deaths have contributed the most to the rise in homeless mortality in recent years, according to a study released by the county health department last October. That study also found that between 2013 and 2018, the number of homeless county residents who died almost doubled and that homeless people have also been dying at a faster rate.

Professionals who treat homeless substance abuse issues attribute the spike in overdose-related deaths to the increasing prevalence of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be 50 times more potent than heroin. “There is absolutely more fentanyl in this region now than there was, say, three years ago,” William D. Bodner, special agent in charge of the federal Drug Enforcement Administration’s L.A. field division, told Capital & Main in November. The second-most common cause of death in 2019 was coronary disease, which accounted for 25 percent of the deaths for which a cause was known, while accidental drug overdose accounted for 30 percent, according to the coroner’s office.

Mental health and/or substance abuse problems afflict 29 percent of the county’s homeless residents, according to the county’s annual homeless count. Protecting addicts from a contagious disease like COVID-19 presents added challenges, says Lee Raagas, CEO of the Skid Row Housing Trust, whose agency provides 1,800 units of supportive housing for recently homeless individuals. “People can’t self-isolate if they’re not in the right frame of mind to understand what that means,” Raagas says. At the same time, there are fewer caseworkers in the field due to public efforts to reduce the spread of the coronavirus.

Trailing those causes of fatalities were transportation-related accidents — a category that includes people dying after being struck by trains or cars, sometimes in hit-and-runs (11 percent), followed by homicides (7 percent) and suicides (5 percent). Other causes of death were pneumonia, liver disease or cirrhosis, cardiac-related illness and sepsis.

In 2019, whites accounted for about a quarter of the homeless, roughly their share of the county’s population, but they accounted for 37 percent of homeless deaths in 2019. African Americans, meanwhile, accounted for 33 percent of the homeless population, about four times their share of the county’s population, and 25 percent of the deaths.

Public health officials hypothesize that African Americans and whites “experience different pathways to becoming homeless, with white homelessness being precipitated more often by physical and mental disability and African American homelessness being triggered more often by poverty and discrimination,” according to the county health department’s October study.

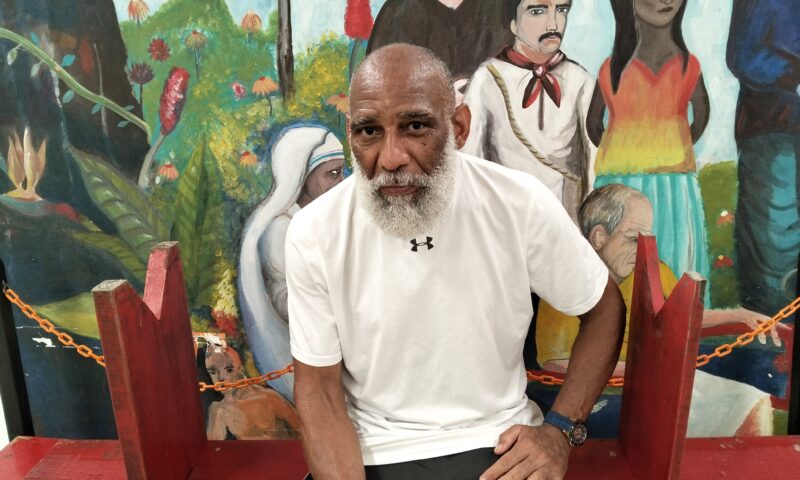

As many as 400 people who do not have housing could die of the coronavirus in Los Angeles County alone, and 2,600 could require hospitalization, according to researchers at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. As of June 15, at least 506 L.A. County residents who are homeless have tested positive for the virus, including more than 90 at the Union Rescue Mission on Skid Row. Gerald Shiroma, a 56-year-old resident and driver at the Union Rescue Mission, who was one of the first to test positive for COVID-19 on Skid Row, died from complications from the virus on April 8, according to a video message posted by Reverend Andy Bales, the CEO of Union Rescue Mission. “Gerald was a gentle soul. He cared deeply about others. He served others,” Bales said.

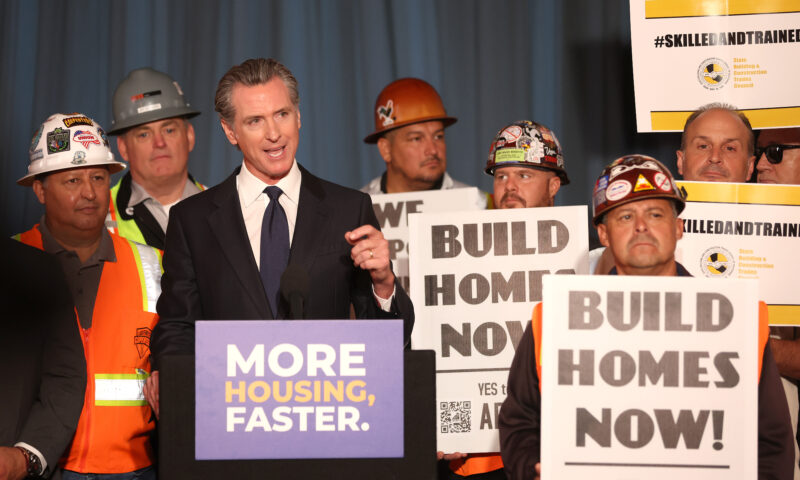

In early April Gov. Gavin Newsom launched Project Roomkey, an effort to secure hotel rooms that would allow the state’s most vulnerable homeless residents to self-isolate. As of June 15, 3,766 people had found shelter in those rooms, far short of the county’s goal of housing 25 percent of the more than 60,000 homeless people in the region, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

StrandedNovember 25, 2025

StrandedNovember 25, 2025‘I’m Lost in This Country’: Non-Mexicans Living Undocumented After Deportation to Mexico

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 21, 2025Seven Years Into Gov. Newsom’s Tenure, California’s Housing Crisis Remains Unsolved

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 28, 2025Santa Fe’s Plan for a Real Minimum Wage Offers Lessons for Costly California

-

The SlickNovember 24, 2025

The SlickNovember 24, 2025California Endures Whipsaw Climate Extremes as Federal Support Withers

-

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025

Striking BackDecember 4, 2025Home Care Workers Are Losing Minimum Wage Protections — and Fighting Back

-

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 8, 2025This L.A. Museum Is Standing Up to Trump’s Whitewashing, Vowing to ‘Scrub Nothing’

-

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025

Latest NewsNovember 26, 2025Is the Solution to Hunger All Around Us in Fertile California?

-

The SlickDecember 2, 2025

The SlickDecember 2, 2025Utility Asks New Mexico for ‘Zero Emission’ Status for Gas-Fired Power Plant