Environment

Last Battle for a Toxic Community

A warehouse project is planned for a Los Angeles area that is among the very worst in the state for the threats that toxic cleanups and hazardous wastes pose.

CYNTHIA MEDINA lives near the nexus of the 110 and 405 freeways with four generations of her family—her mother, husband, four children and two grandchildren. For 32 years she and her loved ones have endured a long history of illnesses here.

One of her daughters, Medina says, was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at 19 and is now, at 39, largely bedbound. Another son was diagnosed at age 9 with diabetes—now 42, he’s clinically blind, she says. All of her children, she adds, have suffered some combination of asthma, skin rashes, bloody noses and allergies. Medina herself has developed diabetes. “I’m in and out of hospital all the time,” she says, noting that many local families suffer similar health problems.

While she can’t know for certain, Medina suspects that the toxic legacy of her neighborhood —an unincorporated area sandwiched between the cities of Torrance and Carson—could have contributed to her family’s health issues. That’s one reason why Medina belongs to the Del Amo Action Committee (DAAC), a small but highly motivated group of local residents who have spent more than 25 years fighting both for the cleanup of legacy contamination, and against further encroachments from industry. “I think we’ve had our unfair share of illnesses,” she says.

Now the group, along with other residents, is embroiled in a new battle to halt a proposed warehouse and trucking facility that they fear will bring heavy traffic and air and noise pollution to an area already overburdened with all three. In this highly industrialized part of the L.A. metropolitan area, it’s a familiar tug-of-war that pits economic arguments against quality-of-life concerns.

Don Garstang, a 34-year local resident, calls it “by far the biggest remaining issue” in the area, and though the land is zoned for industry, given the neighborhood’s toxic history, he believes it should be rezoned for other uses, including the construction of single-family homes. He and other residents have been in communication with the developers and local government agencies about the proposed facility, but “it remains to be seen if the concerns will be taken seriously,” he adds.

The residents face an uphill battle. According to Nooshin Paidar, supervising regional planner with the Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning, zoning laws handcuff what restrictions the department can enforce, although it will continue to study the proposal while it’s under a California Environmental Quality Act review. The department takes “very seriously” the residents’ concerns about the development, she adds. “It’s really close to residences so we understand that they’re very incompatible uses.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Public Health (DPH) wrote in an email that “a significant concern with this project is the increased truck traffic and pollution near homes already burdened by the Del Amo/Montrose Superfund Site.” The spokesperson pointed to a January DPH letter saying the department concurs with “initial” truck traffic restrictions. Nevertheless, the spokesperson added, noise pollution increases from “operational activities in the warehouse” as well as the overall increase in “projected traffic” are not expected to be “significant.”

At the same time, residents like Cynthia Babich, DAAC’s founder and director, voice frustration that, were it not for vocal community members, regulators wouldn’t take into consideration their quality-of-life concerns. “If we are not raising these issues, things [will] just keep going the way that they are,” says Babich, who lived in the area for about five years before she and her family relocated. She has no doubt that fighting for change there is a matter of life and death: “I think people would continue to die in that community and not know why, and more importantly, not know how to change that.”

* * *

THE NEIGHBORHOOD is a predominantly working-class community of about 2,000 residents, mainly Latino. It is also one of the most environmentally burdened in California, factoring in a variety of toxic sources, including the Del Amo and Montrose Superfund sites, air pollution from the Harbor Freeway, and the nearby PBF oil refinery. More specifically, the area is among the very worst in the state for the threats that toxic cleanups and hazardous wastes pose.

The nine-acre development is described in a draft project proposal dated this past March as a warehouse-and-distribution type of land use, including a new 203,877-square-foot concrete building, along with 21 truck loading bays. “The project would allow for activities to occur on-site 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” the draft adds.

“Based on the discussions we’ve had, many community members are supportive of the Project, including several of the Project’s closest neighbors to the east,” writes Brian Wilson, a partner with the West Region for Bridge Development Partners. In a two-page statement, Wilson lays out a list of measures the company will enact to reduce noise and truck traffic in residential areas. “Bridge proposes to invest more than $40 million to transform the site, designing an architecturally attractive, modern building with articulation and extensive glazing on the corners, and adding lush new landscaping and trees on all four sides,” he writes.

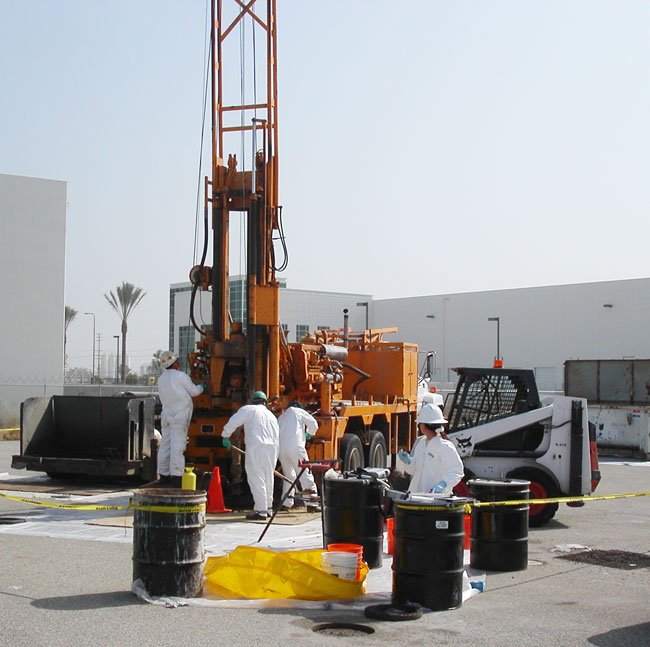

Nevertheless, this project is just the latest commercial venture in a region with a long industrial history. Synthetic rubber was manufactured at the 280-acre Del Amo Superfund site for nearly 30 years, while at the other site, Montrose Chemical Corp. manufactured DDT—the highly toxic insecticide banned nearly 40 years ago. Both cleanups are ongoing. Indeed, the contaminated groundwater has become so deeply entrenched, it will take potentially thousands of years to remediate.

Jim Wells, an environmental geologist who has closely followed both cleanups, emphasized the accumulated physical, psychological and financial impacts of living in the area, and warns that the EPA “doesn’t really have a mechanism [for] evaluating and incorporating into their decision-making all the effects that these sites have upon surrounding communities.”

Which helps explain why DAAC members and other local residents see the few potentially available plots of land as opportunities to introduce splashes of color amidst the tight concrete knot of homes and businesses. The group has put together a 50-page green vision for the area. Despite their frustration at the slow pace of progress, they’ve succeeded in helping to bring a recreational park to a previously toxic 8.5-acre parcel of land.

“We’re just trying to surround ourselves with green wherever there’s space left,” said Babich. “At the end of the day, can’t we just have one less warehouse?”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts