Labor & Economy

Kicked to the Curb: How USC Drove a Bicycle Repairman Into the Street

“Lil Bill” Flournoy’s bicycle-repair shop has a panoramic view of the community that he and his father have served for over 40 years — and of the new USC Village, which has pushed his business into the street.

Aaron “Lil Bill” Flournoy, right. (Photos: Lovell Estell III)

Aaron Flournoy of Lil Bill’s Bike Shop is determined to carry on a family tradition and keep his business afloat. But gentrification around USC has pushed him out of two locations.

On a pleasantly warm afternoon, Aaron Flournoy is busy tightening the wheel on a young woman’s bicycle while three other cyclists wait nearby for his services. His mobile bike repair business, called Lil Bill’s Bike Shop, operates curbside at the busy intersection of Hoover Street and Jefferson Boulevard, directly across from an entrance to the University of Southern California campus.

His location gives him a sweeping view of the enormous, recently opened USC Village complex. Flournoy’s small truck functions as a tool chest/office, and shares the street with a pair of food vans hectic with business from students on their way to classes.

Flournoy, or “Lil Bill,” as he has come to be known, honed his people skills by working with his father for many years. He is well known and well thought of around the campus, and is determined to carry on a family tradition and keep his business afloat.

But to remain afloat, he has had to stay on the move, as the university has forced him to move twice before he took his business to the street. For over 40 years, Flournoy’s dad owned and operated Bill’s Bike Shop on Jefferson. It was a gathering place for locals, and Bill Sr. and Lil Bill catered to the biking needs of USC students and the surrounding community. “They loved him,” Flournoy said of his dad, adding that every year, his father and some family friends would buy cases of food and barbecue and feed the neighborhood.

Bill Sr. retired in January and sold his small building, which sits amidst other nondescript, faded structures. Its current owner is a trust company, and according to Flournoy, the building is one of a few in the area slated for demolition to make room for student housing.

Knowing that his father was retiring, Flournoy last year started his own bike repair business out of a shed in the parking lot of a privately-owned church. He was doing well there, until the school purchased the property.

University officials then told him he would have to relocate, this time near the university’s dentistry school. But when he moved there, he soon ran up against the fact that a bicycle-shop tenant in the new USC Village holds a no-compete clause in its contract with the university. Flournoy then became a street vendor.

Decades of gentrification have profoundly affected the residents, neighborhoods and small businesses bordering the USC campus. There once was a running joke among UCLA students across town about USC’s “tacky ghetto location.” But private developers and the university have succeeded over the years in transforming the area—which more and more is starting to resemble UCLA’s Westwood neighborhood — and in catering to the escalating demand for student housing.

Many of the school’s adjoining streets that were once home to a robust community of working class African-American and Latino families are now occupied by student residences and an expanding territory of fraternity and sorority houses. Over time, this change in the neighborhood has resulted in rising rents and a shortage of affordable housing for residents, many of whom have been forced to relocate.

Poverty, chronic unemployment and underemployment have also taken a toll. Despite the university investing $35 million annually in the community, the median income level for the University Park area hovers slightly above the federal poverty level of $24,600 for a family of four. The 2015 USC State of the Neighborhood Report says that since 2000, there has been an 11.5 percent increase in the number of area families living in poverty.

“When we talk about gentrification, we normally think, ‘Well, that’s good, we’ll have new jobs and wealthier people moving in,’ but the fact that economically vulnerable people will be further impacted or forced out isn’t mentioned,” said Joe Donlin, the associate director of Strategic Actions for a Just Economy and its director of Equitable Development. Donlin’s nonprofit has been working with USC to address some of the economic and social issues surrounding construction of USC Village.

The northwest corner of Jefferson and Hoover – where a strip mall, discount supermarket, small businesses and mom-and-pop eateries once stood – is now wholly occupied by the $700 million resort-style USC Village. Three years in the making, the complex opened in August to great fanfare. It’s a 15-acre development consisting of six buildings with luxury features like a massive dining hall, 30,000-square-foot fitness center, residential suites for students and over 148,000 square feet of retail space. Which brings us back to Aaron Flournoy.

One of the Village’s new retail tenants is Solé Bicycles, a shop selling “fashion forward yet affordable bicycles,” according to its website. Flournoy’s relocation to near the dentistry school was halted when officials told him he would have to pack up and leave the campus because of Solé Bicycle’s no-compete clause. There was to be no competition from other bike businesses on campus. Months of fruitless back and forth with the school included a job offer from Solé.

“I have my own business,” Flournoy said. “I don’t want to work for anybody.” He then left his shed and moved his business to the street in August.

“It’s disgusting the way the school has treated Lil Bill,” SAJE’s Donlin said. Solé Bicycles and the university have not responded to requests for comment.

Lil Bill Flournoy remains optimistic about his business and his recent conversion to street vendor status, and he seems to have adjusted to the many changes that have beset his life.

“I’m on city property so they can’t say anything,” he said with a chuckle. He has much support and many friends around campus. Many students stop by to say hello, and there is an online petition circulating with over 6,500 signatures supporting him.

“I would like to stay right where I am,” Flournoy said. “Being here, the kids can see me, they know me. Being on campus had me under a lot of stress and restrictions, but being off-campus has opened up some new opportunities for me.”

Editor’s Note: After this article appeared, USC emailed Capital & Main a statement that read, in part:

In an effort to give him time to find an alternative location for his business, Mr. Flournoy was provided a temporary space on campus until April 30. Unfortunately, this temporary space is in a parking lot that is not an appropriate location for bicycle repair and activities and is blocking access to disabled parking. . . . Additionally, USC offered Mr. Flournoy an alternative on-campus location near three residence halls, which also was not accepted.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

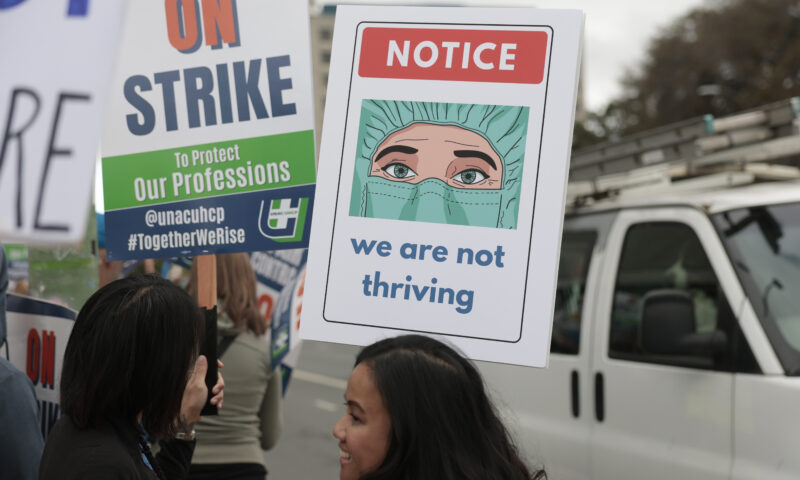

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas