Labor & Economy

Interview: Rick Wartzman on Greed and Conscious Capitalism, Part 2

During his 20-year career as a journalist, Rick Wartzman delved deep into the reality of poverty for a major Wall Street Journal examination of the minimum wage and also mastered the intricacies of corporate finance as business editor of the L.A. Times. In yesterday’s interview with Frying Pan News, the executive director of the Drucker Institute discussed the destructive force of big business’ “shareholder-is-all culture.” In today’s conclusion, Wartzman talks about Walmart, the outlook for unions and the need to build an education-based service economy.

Frying Pan News: How would you characterize Walmart, which is now trying to move into L.A.’s grocery market?

Rick Wartzman: Walmart is less Drucker-like than Costco, certainly, but increasingly presents a complicated picture. They’ve always paid lousy wages and benefits, squeezed suppliers until they choked and accelerated the race to the bottom in terms of low-cost labor. But I’ve always thought the plus side of the ledger wasn’t empty. Walmart has always done some good with this notion of everyday low prices. That is beneficial for low-income communities. It’s hard to argue that they don’t have an understanding of customer value. You can’t dismiss the idea that there is some social good in offering a whole range of products in neighborhoods that wouldn’t otherwise have access to them. It’s also gotten more complicated by the environmental gains they’ve made. It’s easy to be cynical and say it’s all posturing and PR, but by many accounts they’ve really moved the needle on green corporate practices. So while the things on the plus side of the ledger don’t necessarily outweigh the negatives, there’s no denying that the story is quite complex — and interesting.

FPN: There was a time in America when a unionized workforce was accepted by many corporations as the norm — do you think it would be good for the country if this once again became the norm?

RW: Yes, with a caveat. You can draw a straight line between the decline of organized labor and those stagnating wages that we talked about. Unions clearly had an effect not only on unionized businesses but also on nonunion businesses, which to keep organized labor at bay would give wages and benefits equal to or higher than what unionized businesses could offer. That was a big part of the balanced stakeholder approach; Kodak, for instance, would say to their workers, “Why do you need a union when we take such good care of you?” And they weren’t lying. Unions clearly helped lift everyone’s wages, and you can make the case that more organized labor would put upward pressure on incomes and help to recalibrate an unbalanced society.

The caveat is that there are reasons why unions have struggled — and some are of their own making. In the period beginning with Reagan, government and NLRB hostility to unions made organizing harder. Many companies have also made a concerted effort to keep unions out, and plenty have gone so far as to cheat or break the law. It’s been an unfair fight in some ways. But unions have done quite a bit to shoot themselves in the foot, as well. Not all unions acted this way, but the labor movement in general became as fat, happy and inefficient as companies did in the ‘70s and ‘80s. When companies started going into decline, unions did too. The difference is that companies figured out how to pick themselves back up, whereas unions haven’t. They are stuck in an old mode and they haven’t innovated enough. A lot of union leaders became as bad as corporate CEOs, looking out for themselves and not the workers. And the union movement has to face up to that before there is hope of a real turnaround.

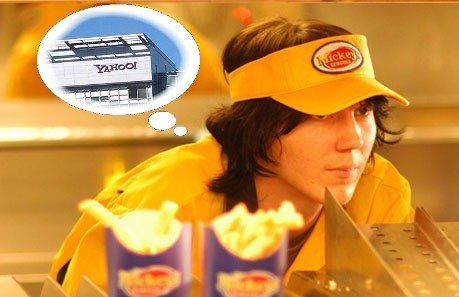

FPN: Where are the good jobs of the future that will allow us to rebuild the middle class?

RW: We’re going through a wrenching change. We are in a post-industrial society. People with the knowledge win. The solution lies in creating as many good knowledge workers as we can, in creating a well-educated, creative, nimble workforce. In short, that means fixing the schools. But that, of course, is an incredibly daunting and expensive task. We have moved to a knowledge economy but we are still cranking out kids as if we are in a manufacturing economy.

FPN: But why can’t the service jobs of the 21st Century be good middle-class jobs like manufacturing jobs became in the 20th Century?

RW: One way that those jobs became good middle-class jobs is that manufacturing productivity soared from the end of World War II until the early 1970s. We now need to increase service-sector productivity to see the possibility of raising all boats again. You need enough money flowing through the system.

That said, none of this will matter if all of the gains keep going to those at the top of the heap. Really, we need to take all of these steps simultaneously — better educate our children and provide meaningful lifelong-learning opportunities for adults; increase knowledge-worker and service-worker productivity; and get away from a shareholder-is-all culture.

FPN: So how does the culture shift happen in corporate America — who leads it?

RW: There are signs of it happening. There are companies, some of which have united under an umbrella group called Conscious Capitalism, that are beginning to question the shareholder maximization model. There is also an intellectual movement, which includes academics like Harvard’s Rakesh Khurana, saying that maximizing shareholder value is flat-out wrong. And then there are organizations, like the Drucker Institute, which are providing alternative ways to think about these issues.

FPN: What is the L.A. media missing in their reporting on L.A. and its economy?

RW: Resources. It’s impossible to have the same level of quality in a newspaper with 600 reporters and editors, rather than the 1,200 or so we had at the Times when I left. More generally, there’s a void in writing about the working poor and working class and middle class in Los Angeles. Yes, there are great exceptions to that. But in general, there’s a hole in terms of thinking holistically about working folks, understanding these people’s lives, what they are up against, what are the big forces that are shaping huge pieces of our community.

FPN: What are the top three things the next mayor of L.A. should try to achieve?

RW: I would put education at the center of the agenda. Even though the mayor can’t run the schools, Villaraigosa was onto something hugely important. We need to create more knowledge workers. We also need to prepare those who whose careers will fall somewhere in between pure knowledge jobs and service jobs – technicians who will use their hands but also need to use their heads. They need some math and English skills. But, most important, they need to know how to learn — and continually learn — because their jobs are going to change so much and so quickly over the course of their lives. There’s a lot a mayor can do to keep flogging the issue in way that would be useful, encouraging more and more piloting to find things that work and scale them.

Second, a new administration might develop a business park, but one that would focus on service jobs instead of industrial jobs. The idea would be to bring in great thinkers from USC and UCLA and Claremont Graduate University to work with businesses to figure out how to raise service worker-productivity. You start with a blank slate: What would it take to make service jobs productive enough, and provide enough profit, to become real middle-class jobs?

Last, business gripes all the time about red tape and taxes. And a lot of their complaints are legitimate. Is there, then, some kind of grand bargain in which the city would strip away a lot of red tape and some taxation but, in turn, get companies to do something that would be of great social benefit? Would the Chamber of Commerce accept a citywide living wage, for example, in return for a much healthier business climate? Suppose the new mayor went to the business community and said, “Don’t just automatically reject the idea of a citywide living wage. Tell me what I’ve got to do to make it acceptable for you.”

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care