Coronavirus

I Bus Tables at Salazar. My Co-workers Are Desperate.

Restaurant workers at a Los Angeles eatery were looking forward to the high season of tips and extra hours. Then came the pandemic.

Co-published by Fast Company

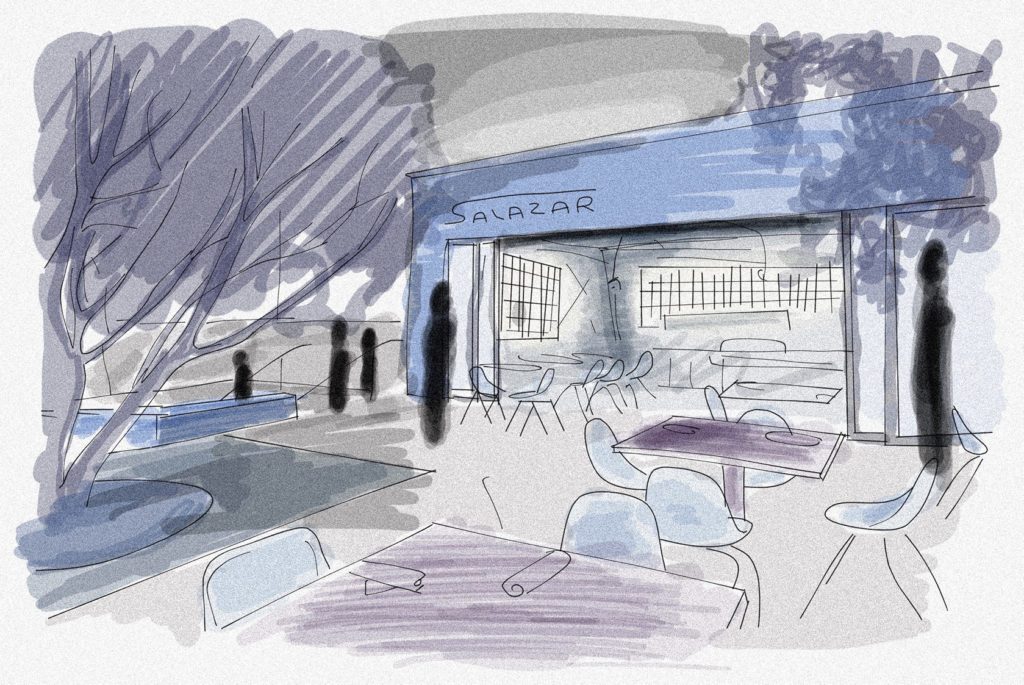

If you’ve eaten at Salazar, the popular Frogtown taco spot, odds are I’ve gone home covered in your leftover guacamole. Ten months ago the restaurant hired me as a busser. I ran around with trays creaking under piles of dishes and drinks, dodging celebrities and dogs in the race to reset tables as fast as possible. The health app on my phone counted 17,000 steps per day, and after my shifts my legs ached like I’d gone jogging. On a busy night, I could take home $130 in tips.

Co-published by Fast Company

Those days seem far away. On March 15, Gavin Newsom requested California restaurants close to dine-in customers. The next day, Salazar general manager Mark Ramsey wrote on Schedulefly, the website we use to coordinate shifts, that Salazar would be closed to both dine-in and take-out customers until at least April 1, a date subsequently extended to April 19.

Madeleine: “I don’t have savings. I don’t have a plan, I really don’t.”

Server Blaine Vedros read about the governor’s orders on his phone at the end of his dinner shift on March 15, the last night the restaurant was opened. “We had to dump a lot of food,” says Vedros. “I came home with three pounds of raw tortillas and a bunch of taco meat.” Vedros and his fiancée survived on the food for the first four or five days of the quarantine.

“No, fuck no, I don’t have savings,” says Madeleine Kunkle, a server and artist. Kunkle and I bonded this winter over a shared interest in Bernie Sanders and Johnny Knoxville.

“I don’t have a plan,” she says. “I really don’t.”

Some servers are starting families. Madison Dirks and his wife are busy caring for their son, now almost 2, and are expecting twins in July. Doctors say the pregnancy will be high-risk. Dirks’ wife quit her full-time job in November to care for the baby, and they spent their savings trying to get through the winter.

Steve: “Maybe if I get my tax return in time, I borderline will be able to make rent this month, and that’s it.”

“Stressed is probably not a big enough word for how we’re feeling,” he says.

Salazar was employing 79 workers in total: 37 in the front of house, 26 in the kitchen, and 11 in the bar, with five managers who also don’t receive pay in the quarantine supervising the operation.

In the winter our shifts are cut and tips plummet as customers leave the cactus-lined outdoor patio for indoor venues. When I stopped carrying umbrellas and started wheeling heaters in the fall I knew it was time to reel in my spending. The spring months are supposed to bring relief. But the virus also threatens the summer boom, when management adds around 15 tables to the floor plan, the hosts run two-hour waits, and road-bikers roll in from the Los Angeles River drenched in sweat for a mid-ride taco (or margarita). Summer is the time of plenty we rely on to get through the rainy months, when most of us work second jobs.

Sammy: “It’s a restaurant job, but I’ve been doing it for 20 years. This is three days in and I’m going to shoot myself.”

“We just started to see the crowds come back,” says Steve Johnston, a food-runner who says he already borrowed money for January and February rent. “Maybe if I get my tax return in time, I borderline will be able to make rent this month, and that’s it.”

* * *

Sammy Espinoza, a waiter who calls me his straight, white, little brother and likes to tease me at the server station about finding a girlfriend, says he has savings to get by during the quarantine. But Salazar closing its gates also means the loss of a home. “It’s a restaurant job, but I’ve been doing it for 20 years,” he says. “It’s what I do. As much as I am an actor and identify as an actor.”

“This is three days in and I’m going to shoot myself,” he jokes.

Billy: “Restaurants are not getting direct cash infusions

like big corporations are.”

I do not act myself, but as someone interested in writing—also work not necessarily considered profitable by whoever is in charge of the American economy—I feel a kindred spirit with my auditioning co-workers. I find myself doubting my choices this week, fearing a service-industry collapse, but Steve Johnston tells me his belief in acting for a living has not wavered.

“There’s not a lot that’s gonna stop me from doing it,” he says. “Death, maybe death; maybe the threat of actual death.”

Kunkle just turned 26 and will be bumped off her father’s health care plan at the end of March. Salazar’s health care plan for its employees is scant at best. Only full-time staff is eligible, just the managers and a handful of cooks—all front of house employees work part-time—and the coverage offered is only narrowly cheaper than external options, according to employees who used the plan.

Following the impact of coronavirus, Billy Silverman, Salazar’s principal owner and the son of producer and studio executive Fred Silverman (All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, M*A*S*H), would consider providing health care to part-time workers too.

Silverman says the small business loans included in the $2 trillion stimulus package President Trump signed into law last Friday mean Salazar can survive, for now. The restaurant owes its employees two weeks of paid leave on April 2, as mandated by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, and the restaurant “just barely” has the cash to pay it, he says, in large part because Salazar enjoyed a warm, and thus busy, February. That the loans come as tax credits, though, means restaurants without the cash on hand will close or turn to layoffs, he imagines.

“I’m cool with paid leave, but I don’t think there’s a restaurant in the world that just keeps two full payrolls in the bank, you know, in the event of pandemic or worldwide catastrophe,” he says. “Restaurants just don’t have the money to pay out, and they’re not getting direct cash infusions like big corporations are.”

My co-workers are largely unmoved by the stimulus package, which expands unemployment benefits and promises $1,200 to all Americans making less than $75,000 per year.

“The only thing it does is make it that, let’s say if I wanted to choose out of all the bills that I have, [I can] pay rent and go food shopping once,” says Johnston. “It doesn’t help me.”

$1,200 falls short of Dirks’ requirements too: $3,000 per individual would be the minimum amount that could actually help him and his family.

“Then it wouldn’t seem like—like so impossible,” he says.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care