Latest News

Honoring Robert ‘Bob’ Moses: A Champion of Equality

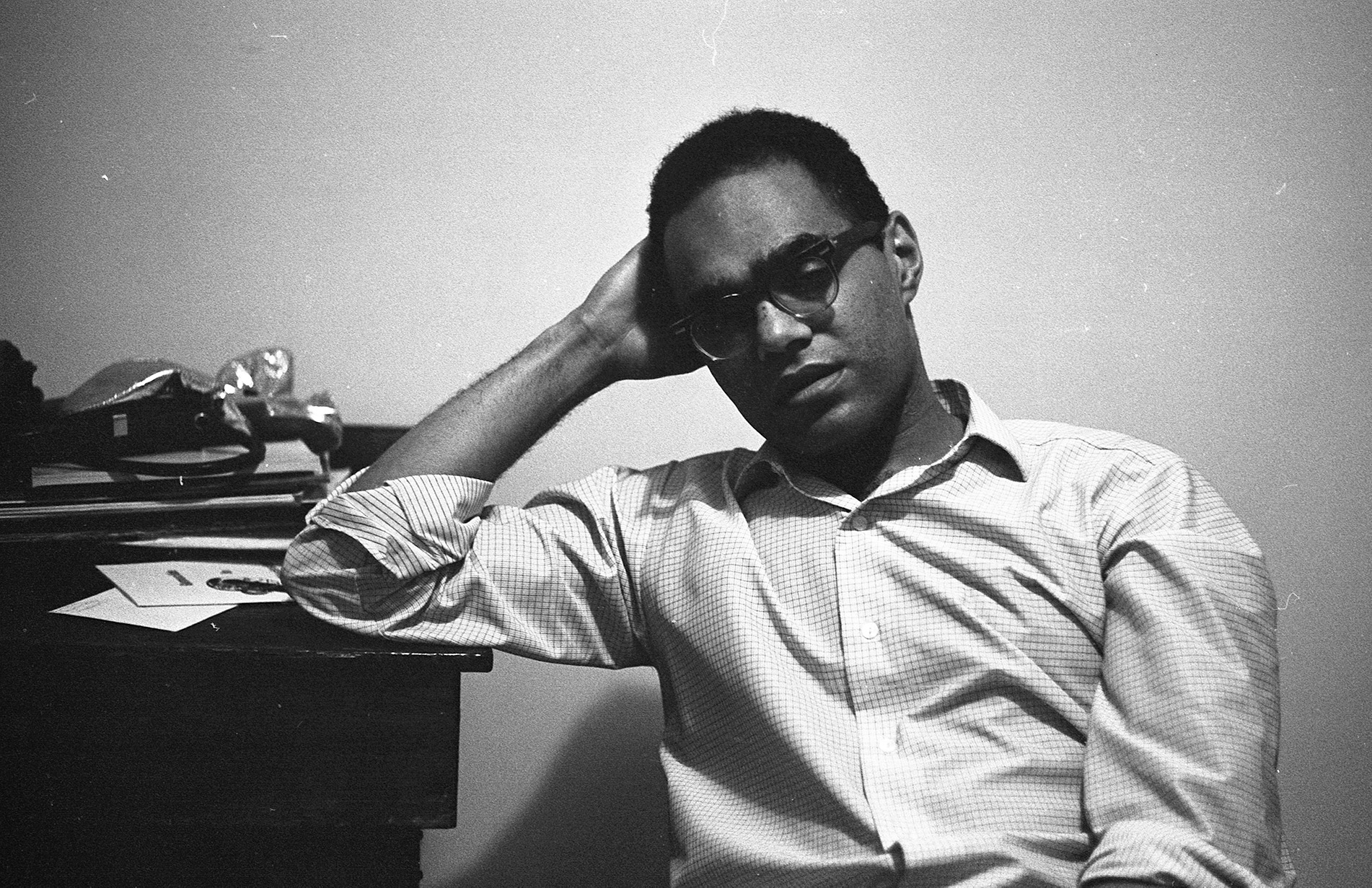

The civil rights activist is remembered for fighting on behalf of the most vulnerable.

During the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, Robert “Bob” Moses asked the crowd to stand. We were in the large gymnasium on the campus of Tougaloo College, a private historically Black college in Jackson, Mississippi. He asked us to repeat after him as he recited the Preamble to the Constitution: “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

Moses wanted to remind us of the promises of the preamble — justice, tranquility, welfare, liberty, posterity. It was with these words that the native New Yorker, born the son of a janitor and homemaker in 1935, set out for Mississippi in the early 1960s. He wanted to change the Jim Crow status quo that had kept African Americans and the nation’s most vulnerable from economic, educational, and political opportunities.

It was a courageous act to want to work in Mississippi, known as the most racist state in the nation. The 1955 brutal lynching of Emmett Till had sealed Mississippi’s reputation as a place hostile to Blacks. In a 1961 letter from the Magnolia jail, Moses described Mississippi as “the middle of the iceberg.”

Unlike many national civil rights leaders, Moses was not a charismatic orator who corralled a crowd to rousing applause. He was quiet, soft-spoken, thoughtful, strategically minded. He didn’t fly into a city, march in his Sunday best and leave. He dressed in overalls, T-shirts and jeans. He learned the lay of the land from local leaders and stayed with local people. He lived among those he wanted to help.

Moses was the mastermind behind the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project in which more than 700 Black and white college students traveled to Mississippi to register Black voters.

Moses was beaten, jailed and threatened by those who didn’t take too kindly to his work. As the Mississippi field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he organized sharecroppers and empowered those like Fannie Lou Hamer to speak up and speak out about the injustices they endured under the system of Jim Crow segregation.

Moses was the mastermind behind the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project in which more than 700 Black and white college students traveled to Mississippi to register Black voters. They set up Freedom Schools and taught literacy and civic education. The goal was to put a spotlight on the way people lived and were treated in Mississippi.

Bob Moses died on July 25 at his home in Hollywood, Florida. He was 86. In a 2002 interview, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Taylor Branch described Moses as the “father of grass-roots organizing.” Historian David Garrow, another Pulitzer Prize winner, told The Washington Post that Moses was “more poet than politician.”

* * *

Charles “Charlie” Cobb arrived in Mississippi in 1962 as a 19-year-old Howard University student. He was on his way to Houston for a young activists’ civil rights conference but never made it to Texas. He ended up staying in Mississippi nearly five years working alongside Moses, registering Black voters and working in Freedom Schools.

“What struck me and still stands out in my memory is this quiet determination and commitment that he had,” says Cobb. “You don’t notice it right away. It doesn’t manifest itself in speeches. He had an unusually strong determination and focus.”

Moses would go on to be involved in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the Poor People’s Campaign, and the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. After his stint in Mississippi, he taught mathematics in Tanzania from 1969 to 1976 before returning to the U.S. The holder of a Harvard Ph.D. in philosophy was named a MacArthur Genius Fellow in 1982 and used the grant to create the Algebra Project, “which uses mathematics as an organizing tool for quality education for all children in America.”

“All his life was dedicated to working on behalf of people at the bottom of the social ladder.”

~ Courtland Cox, chair of the SNCC Legacy Project

Moses’ final years were focused around education and math literacy. In the end, his legacy will be how he worked to connect the link between education and citizenship, something he learned during his years in Mississippi, says Cobb.

“Much of the conversations have been focused on his work in civil rights in the South, but the Algebra Project was a much, much longer period of time,” says Cobb. “Bob believed that you cannot function in today’s society without education, specifically math, and that we live in a system that discriminates in regard to that when it comes to non-white people. He made a commitment to challenge that and change that.”

* * *

Courtland Cox was a Howard University student and a member of SNCC when he traveled to Mississippi to work on civil rights. He recalls a story Moses liked to tell about organizing a group of Black sharecroppers to go to a courthouse and register to vote. A federal judge asked the young activist why he was working so hard to register people who were illiterate. Moses pointed to the systems that were used to block access to education for Black Mississippians, limiting opportunities and creating illiteracy in the state.

Cox notes that Moses tried to get people to succeed in an industrial economy through voting, and he used algebra to get people to succeed in an information economy.

“All his life was dedicated to working on behalf of people at the bottom of the social ladder,” says Cox, chairman of the board of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Legacy Project. “Whether he was dealing with civil rights or whether he was dealing with math, he wanted to deal with people in the most difficult economic and political circumstances.”

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.