Culture & Media

Hockey League Turmoil: Gary Bettman’s Ruler

Over the past year we’ve written quite a bit about the business of sports, and unfortunately, lockouts in the National Football League (NFL) and National Basketball Association (NBA) have given us quite a bit to discuss. We haven’t said much about things going on in the National Hockey League (NHL), perhaps because the script has come to seem so familiar, and there seemed little doubt that after some fireworks, things would finally result in a an unsatisfying deal that got everyone back on the ice a bit late, but in time for a meaningful season. Now it’s December, and they still ain’t playing.

Hockey’s labor history is a sorry one, as the league’s union was run for decades by a shill for the owners who stole money and helped the bosses keep the players in poverty well past the point you’d think that’d be true. In the ’90s, however, players started to make real money, in line with other sports. Unfortunately, the league wasn’t growing. Or rather, it wasn’t growing in popularity or revenue. It was expanding into new cities — places like Florida and Arizona – with, shall we say, limited experience with hockey. That meant what revenue there was now shared among weak markets not capable of supporting hockey. The disparity in revenue between, say, Toronto and Carolina, combined with the lack of a salary cap, meant that owners found themselves paying salaries that totaled about 70 percent of revenues, well above the norm in other sports leagues.

This led to a lockout that cost the 2004/2005 NHL season. The result was a collective bargaining agreement, widely seen as a huge victory for owners, that created a salary cap; that cap started in the low 50s, and escalated only as revenues grew. Revenues did grow, nearly doubling in the past eight years, so in 2011/2012, players earned 57 percent of “hockey-related revenue,” which is more or less where the NBA and NFL were before their recent contracts.

This latest fight shouldn’t be much of a surprise in many respects. After all, the other two leagues just won concessions, so the NHL certainly wants them, and NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman was once the heir apparent to NBA head David Stern. The players hired Donald Fehr a few years back; Fehr was the long-time head of the baseball players union, which under Marvin Miller and, to a lesser extent Fehr, was seen as extremely effective.

The fight has had its twists and turns, but here’s the basic outline. The owners proposed reversing the revenue split so they’d get 57 percent and players only 43 percent, with the hopes of actually getting to a 50-50 split. They’ve gotten that. The owners wanted a cap on the number of years any individual player contract could be. They’ve gotten that. The two sides have agreed on pension contributions, on the definition of “hockey-related revenue” and on something called the “make-whole provision” (if owners cut salaries from 57 percent to 50 percent, they’d in fact be cutting salaries in contracts – some signed mere days before the collective bargaining agreement expired, and players rather understandably cried foul about this).

All of this seems to point toward a season and a deal, which is more or less what Donald Fehr was telling people last week at a press conference. From the looks of things, he intimated, those involved in negotiations hoped to wrap things up that night or the next day. And then he left the stage and checked his voice mail. A few minutes later he returned to the podium to tell people “there’s been a development. It’s not positive.”

Apparently the NHL had left a message canceling negotiations and pulling their offer. They’d done so because rather than simply respond yes or no to their most recent proposal, the union made a counter offer. The counter offer was simple: a) the owners want a 10-year agreement, and the players would agree to eight (the owners had started at five); and b) the owners want individual contracts capped at five years, and the players would agree to eight years.

At times in negotiations, the issues that divide two parties are real and substantive. The merits and justice of each side may be debated, but the economics or facts are different. This is not that.

Indeed, all too often labor negotiations are not about that. Instead, they are about power. The NHL Players Association has never before had a legitimate union leader, much as, 50 years ago, the Major League Baseball Players Association did not. The MLBPA hired Marvin Miller away from the Steelworkers. Miller proposed to treat baseball players as workers and union members, which meant viewing the owners not as patriarchs who knew what was best for the game or for the players, but as owners acting in their own best interests. For years, baseball owners tried to fight Marvin Miller, not to cut the best financial deal, but to ensure they maintained control. Eventually they lost control, and they lost every labor battle they entered into. (They cried all the way to the bank, as owners like George Steinbrenner turned his $10 million investment in the Yankees into something worth about $3.4 billion, according to Forbes).

Something similar is happening now. The NHL is not trying to get the best deal. They’ve got that and more. They’ve bested the deal won by the NBA and NFL, and significantly improved upon what they won eight years ago. Their league is growing, and the last thing a league like this one—a sport that could be one of the “big four” or could fall back to second-tier status—needs is another lost season, or angry sponsors (one has threatened to sue them), or canceled TV contracts.

Things fell apart last week for one reason—the players wanted to bring Donald Fehr into the room to close the deal, and the owners and Bettman said doing so was a “deal-breaker.” Put another way, the NHL owners are willing to cancel their season to avoid the perception that Donald Fehr got the deal done.

The next time someone tells you it’s not about the money, they may be right. For employers, when it comes to unions, it’s about the power.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

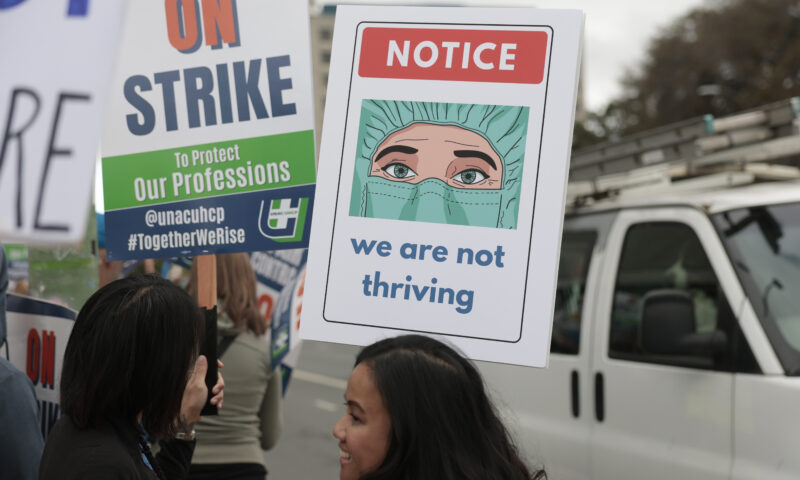

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas