Culture & Media

“Hansel & Gretel Bluegrass” — A Different Kind of Hunger Game

The 24th Street Theatre has a reputation for producing quality theater suitable for everyone from 8 to 80 years old. Hansel & Gretel Bluegrass, Bryan Davidson’s compelling musical adaptation of the fairy tale about two hungry and imperiled children, is the company’s latest effort.

Angela Giarratana and Caleb Foote as a Depression-era Hansel and Gretel (Photo by Cooper Bates)

The 24th Street Theatre has a reputation for producing quality theater suitable for everyone from 8 to 80 years old. Hansel & Gretel Bluegrass, Bryan Davidson’s compelling musical adaptation of the fairy tale about two hungry and imperiled children, is the company’s latest effort.

Directed by Debbie Devine, the piece is notable for its eternal theme: the plight of children abandoned because of economic crisis. Indeed, it’s widely believed that the origins of “Hansel und Gretel” (published by the Grimm brothers in 1812) rose out of Europe’s Great Famine (1315 to 1321) when, unable to feed their kids, parents abandoned them in the woods.

The practice of child abandonment (and infanticide) has continued through the centuries. Catholic churches in 17th-century France helpfully furnished a sort of cradle-shaped drop-box where mothers could deposit their infants for permanent sanctuary. In the U.S., Civil War orphans and other unwanted youngsters were transported, by trainloads, out West for adoption. And today, thousands of minors from impoverished and war-torn lands south of our border make their way here unaccompanied .

This makes the play at hand both timely and universal. Davidson’s adaptation is set in eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression, its narrative relayed with a sly, slithery folksiness by a radio DJ (Bradley Whitford on video), who takes periodic nips from his personal flask as he sagely spins his tale. The Duke, as he calls himself, has received a letter from a young boy, the son of an out-of-work coal miner, disturbed by the wails of his younger sister, weeping because she’s hungry. Her crying angers the boy, and in his letter he writes that he wishes she’d never been born. So the Duke begins narrating the story of Hansel (Caleb Foote) and Gretel (Angela Giarratana), the children of another pink-slipped miner who, in desperation, guides them to the middle of the forest and disappears, hoping against hope they will be able to survive on their own, since he has nothing to offer them.

Left alone, the brother and sister clash: Hansel, a macho boy, is good at practical stuff and protective of Gretel, but he’s also bossy and dismissive of her love of music and overall sensitivity. When they meet the blind Mountain Woman (Sarah Zinsser), Gretel’s resentment of her brother propels her into this shady lady’s clutches, even as the wary Hansel makes an unsuccessful effort to escape, and nearly dies before Gretel wakes to her own folly and manages to save him.

This gender-spiked conflict plays out beautifully under Devine’s astute direction. But while the performers are spot-on — Foote and Giarratana especially interact with rhythmic grace —it is the tapestry of light (Dan Weingarten), sound (Christopher (Moscatiello), set (Keith Mitchell), music (the Get Down Boys) and splendid videography (Matthew G. Hill) — the latter a vital visual element of the narrative’s progression — that make the piece so memorable.

Hill’s artistry reflects off Mitchell’s eerie, fantastical grotto of a set — the perfect backdrop for a myth, even as it suggests the ominous caverns of a coal mine. The sequences where the Duke appears, larger than life, serve as a bridge to our own culture, give or take a few decades, in tandem with the band, who appear in silhouette, and whose music mingles a plucky beat and a plaintive sadness.

24th Street Theatre, 1117 West 24th Street, Los Angeles; Sat. 3 & 7:30 p.m.; Sun, 3 p.m., through December 11. (213) 745-6516 or www.24thstreet.org

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

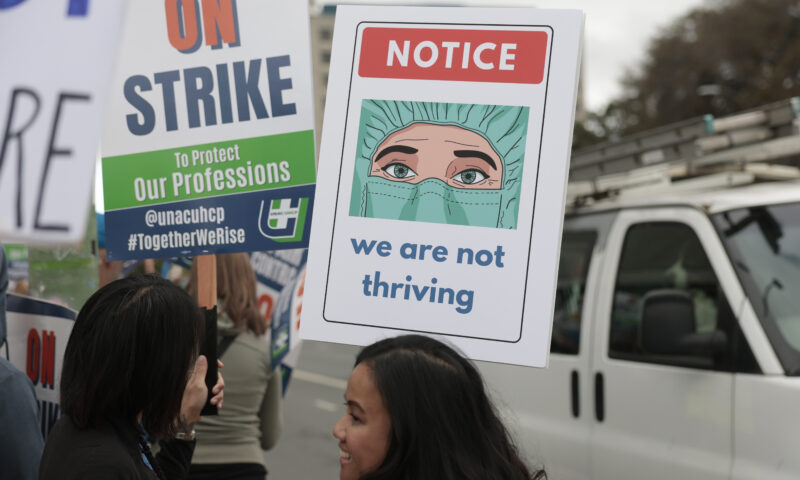

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 15, 2026When Insurance Says No, Children Pay the Price

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026

The SlickJanuary 19, 2026Seven Years on, New Mexico Still Hasn’t Codified Governor’s Climate Goals

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.