Latest News

Gustavo Arellano Talks About Orange County as Vanguard and Old Guard

Disneyland revolts, immigrant NIMBYs, the best xiu mai and more of what makes OC the place where stereotypes go to die.

It is hard to find a better guide to Orange County than Gustavo Arellano. Previously editor of the OC Weekly, Arellano moved to the Los Angeles Times in 2018 as a features writer and columnist. A self-described “nerd,” he has spent decades uncovering Orange County stories that others overlooked or ignored, reporting primarily on the growth of the Latino population and power in the OC and the predictable backlash.

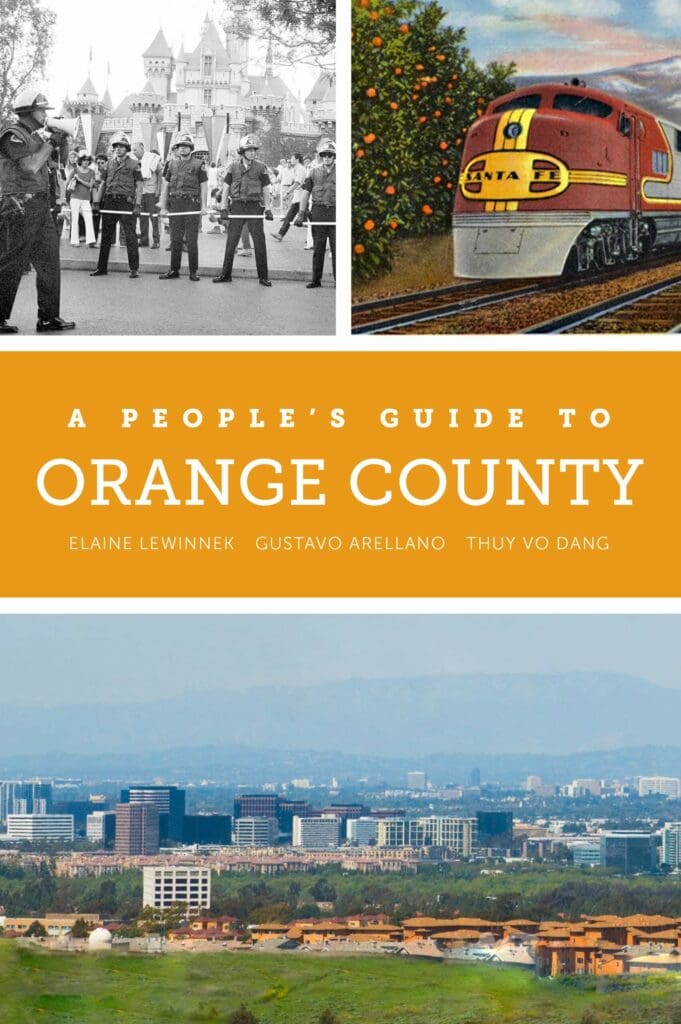

Arellano has teamed up with Elaine Lewinnek, a professor of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton, and Thuy Vo Dang, curator of the Southeast Asian Archive at UC Irvine, on the book A People’s Guide to Orange County. Inspired by Howard Zinn’s bottom-up examination of American history, A People’s History of the United States, the authors outline the labor wars, immigrant rights campaigns and cultural and political shifts that have roiled and transformed Orange County. If you read closely, you can also find a pointer to the best “xiu mai,” or Vietnamese pork meatballs, in Westminster. Capital & Main interviewed Arellano from his lifelong home, Anaheim.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Capital & Main: A People’s Guide to Orange County has a bit of Howard Zinn and a little bit of Anthony Bourdain. What readers might be interested in this book?

Gustavo Arellano: Anyone who has any interest in Orange County, whether it’s someone who wants to learn more about where they’re from, or someone who wants to confirm their hatred of Orange County or their curiosity about why Orange County is such a peculiar place. I hope when they read it they get surprised, again and again.

You break up the book into chapters based on different areas of Orange County: North and South County, the canyon areas, the coastal cities. What distinguishes these areas?

People in Anaheim or Santa Ana do see themselves differently than people in South County or the beach areas. Part of it is different historical development and part of it is demographic.

In a recent Los Angeles Times column, you muse about how Los Angeles could be embracing an “Orange County state of mind.” What is that state of mind today, or would it be more accurate to describe it as “states of mind?”

In a recent Los Angeles Times column, you muse about how Los Angeles could be embracing an “Orange County state of mind.” What is that state of mind today, or would it be more accurate to describe it as “states of mind?”

States of mind is a better way to put it. When I say the Orange County state of mind, I’m obviously noting the traditional stereotype of Orange County, which is the old Orange County, a place that’s paranoid and sets itself apart from Los Angeles. The current Orange County district attorney, Todd Spitzer, is running for reelection, and his campaign hashtag is #NoLAinOC. It’s a place, in the stereotype, that is hostile to anything progressive. But one of the themes of the book is that there has always been resistance and a willingness to fight back. But still, a lot of that paranoia and discrimination is latent here.

Give some examples.

For instance, one of the most Orange County things I’ve ever seen happened a couple years ago. We had 2,000 people from Irvine going to the County Board of Supervisors meeting protesting because the county wanted to place a temporary homeless shelter in the Great Park in Irvine, which at the time was basically abandoned. All these people are coming in saying we can’t allow homeless people in our community. These were immigrants, Asians, people from the Middle East, I’m sure even a couple of Latinos in there, sounding just like the white supremacists of the 1950s. It was incredible. As much as Orange County might change, some parts of it will never change.

“Orange County needs to create an industry that’s for itself and sustainable. We need white collar jobs in tech but also union manufacturing jobs to make it a more equitable place.”

Different narratives have been constructed about Orange County. One is that it’s a bastion of right-wing reaction — the John Birch Society, John Wayne white machismo and Proposition 187 had fervent support there. Are there other narratives that interest you?

I spent an entire career finding other narratives when I was at the OC Weekly. We’ve been majority-minority since 2004. We rejected Trump twice. We are purple now. But we used to be the place, as Ronald Reagan said, “where all the good Republicans go to die.” I’m also interested in how the façades of the Orange County dream are being exposed to the rest of the world. The Disneyland workers’ revolt, led by UNITE HERE Local 11, is just showing how the “Happiest Place on Earth” is not as tidy as Mickey Mouse would have you believe.

There’s a sense in the book that Orange County can be analyzed through a series of different states of capitalist development: big agriculture, citrus capitalism, real estate speculation, the military-industrial complex, corporate tourism. Do you see it that way?

Orange County has always hitched its fortunes to bubble industries. So, we farmed citrus until 1950, when a disease started killing all the citrus trees. Then we hitch our ride to suburbia, expanding until you can’t build anymore. Now housing is impossibly expensive. To a lesser extent the aeronautics industry, where Boeing or Rockwell were connected to the defense industry, and when that ended, it crushed primarily the upper-middle class. Orange County needs to create an industry that’s for itself and sustainable. We need white collar jobs in tech but also union manufacturing jobs to make it a more equitable place.

Unlike San Francisco or Los Angeles, Orange County never had the strong labor movement that anchored a progressive politics.

Right, because Orange County was virulently anti-union. During the so-called Citrus War of 1936, when orange pickers tried to form a union, they were ruthlessly crushed by every law enforcement agency, the American Legion, the California Highway Patrol. Orange County politicians were proudly anti-union. That’s why it’s been very interesting to see the hotel workers union as, at least spiritually, the most powerful union in Orange County.

“Orange County has always sold itself as a place for the dream. All sorts of communities, both intentional and not, have found something here.”

You write about central Orange County that the “less uniform suburban spaces became sites where immigrants, refugees and LGBTQ groups could find a toehold.” What was it about the nature of those suburban spaces that allowed this to happen?

It was cheap rents. Even by the ’70s and ’80s you started seeing white flight. So, you had these strip malls and shopping plazas being abandoned. So, immigrants are coming in. Instead of tearing up their downtown in a place like Santa Ana, Latino immigrants saved these areas, which, ironically, made the area ripe for gentrification. Anaheim basically tore out its downtown to create a big huge shopping plaza that went nowhere. Fullerton went with a bunch of antique stores. Now it’s a “bro” heaven where you just go get drunk. You had the burning of Chinatown, which kept Asian immigrants away until after the 1964 Immigration Reform Act. We never had a significant Black community. It’s never been more than 2%. Latinos effectively played the role of Black people in Orange County in the sense of being the oppressed minority. We were redlined, so we had to find whatever space we could to create those communities.

Disneyland has always loomed large in the imagery of Orange County. A number of writers have described it as a kind of corporate utopia with an obsession over controlling the physical and human environment. What’s your sense of Disneyland’s impact?

It’s still large. I grew up seven minutes away from Disneyland. I just thought it was cheesy and corny, but it’s just gotten bigger and more powerful. I think 40% of park goers are Latinos. It worries me how much Anaheim depends on Disneyland and the hotels and tourists around it for its bottom line. In terms of its politics, it’s not like they give money to anti-immigrant lunatics, even though back in 1994, they did give money to Pete Wilson’s campaign. Wilson, of course, infamously supported Proposition 187. The politicians that it has sponsored have mostly been in Anaheim, and they tend to be middle-of-the-road Democrats and Republicans.

“Orange County is still a place of bubbles, a place where some of these immigrant communities view each other with suspicion.”

Historian and journalist Carey McWilliams wrote about California that there is a “messianic atmosphere” here. You write about places in Orange County that reflect that observation.

Orange County has always sold itself as a place for the dream. All sorts of communities, both intentional and not, have found something here. Orange County has many diasporas. Little Saigon, the largest Vietnamese enclave in the world outside of Vietnam. Little Arabia, one of the largest Middle Eastern enclaves in the United States. It’s that imagination of the dream. You live in a dreamland that can turn toxic very quickly, where you do turn into “fortress Orange County.” Where you do have cities like Irvine or homeowner associations that are, to borrow a line from McWilliams, “fascism in practice.” In their minds you need fascism to protect your dreamland.

How does the diversity of Orange County play out in interesting or disturbing ways?

You also see alliances which provide some hope that Orange County might change. We have Taco Trucks at Every Mosque, which is a collaboration between Latino and Muslim activists during Ramadan where taco trucks serve halal tacos to break the fast and at the same time sign up people to register to vote. But Orange County is still a place of bubbles, a place where some of these immigrant communities view each other with suspicion.

Michael Kazin, one of our best historians, wrote that Howard Zinn’s book flattened the complexity of our history by portraying it as primarily a story of oppressors and victims. Did you have any concern with avoiding that approach?

My work has always been unpopular among a certain segment of the Orange County population. They say, “Why do you always focus on the bad stories about Orange County? Why can’t you focus on the good stories?” My response is, why haven’t you covered some of these stories or why do you willingly distort them so that they become something that’s just a blip in the Orange County narrative? Telling these stories like the Citrus War, where Latinos rose up because they weren’t going to be treated like serfs, besmirched the idyllic narrative that some historians spend their entire careers trying to create. If this book offends the reader, then I think it says more about them then it does about the authors.

Where do you go in Orange County when you want to get away from your bosses at the L.A. Times and contemplate the nature of the universe?

Nowhere. I love to work so I’m always looking for stories. I love to drive, and my wife and I take road trips to Kentucky and Tennessee bourbon country, and I write stories about Latinos in the South. I’m a student, and I’m always trying to learn, so that’s what keeps me moving. I’m just a quintessential nerd.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit