Environment

Global Warming: A Climate of Denial

[caption id="attachment_11199" align="aligncenter" width="432" caption="Mark A. Wilson/Wikimedia"] [/caption]

[/caption]

My wife Susan and I took a short camping trip to the White Mountains. No, not the ones in New Hampshire, but the ones in California, across the Owens Valley from the magnificent Southern Sierra range. We had seen them at a distance for years, but we had not gone there. They are one of the few places where the bristlecone pines live. The oldest on earth, these trees stretch back 4,000 to 5,000 years in age.

I am not sure what I thought we would find. Maybe a few stark snags set against the white mountain sides with a bright blue backdrop of sky. Maybe we would find a few still living here and there, among not much else. Instead, we found groves of the ancient trees, and some just a few years old, grabbing onto the earth like every new generation, the surrounding ground virtually barren of other vegetation.

At the first grove we walked an easy trail that helped us understand the trees and their environment. They grow here and at a few other sites around the Great Basin – the source of much of Southern California’s weather patterns – in dolomite, a white rock uplifted from prehistoric sea beds that makes a great nursery for the trees, nurturing them over the centuries amid harsh weather and providing a perfect place for new ones to sprout.

Then we headed 12 miles up a dirt road to another grove, just as stark, only at a higher elevation. Here we saw more ancients sprawled across a broad saddle, as well as newbies growing out of the rocky mountainside above us. These young trees, the forest service sign read, indicated that the temperature even at this elevation was increasing enough so the tree-line – the line beyond which it was too cold for trees to thrive – was shifting higher. The new trees grew at the higher elevation than the old stand because global-warming was moving their habitat to a higher elevation.

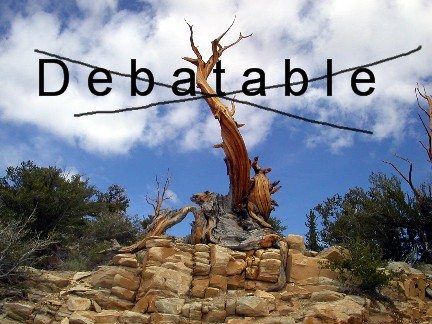

Whether this global warming was human-caused or not was “debatable,” the information sign said, but the increasing temperatures at higher elevations was not an open question. Someone had scratched over the word “debatable.”

When we returned home we discovered that the question is less and less at issue and the situation on the ground more and more apparent. It was the “Controversy of the Week” in one magazine, a special box in Time, the lead “Talk of the Town” in The New Yorker and a major story in the L.A. Times. Apparently, this year’s drought has struck a chord of urgency in the news bureaus of the nation. In 2011 only the southern half of the country experienced partial or severe drought. This year three-quarters of the states are suffering. Significantly, many of these areas are in the breadbasket of America, where corn stalks are producing only partial, twisted ears or are withering on the ground.

Of course, one year’s weather does not make climate change. Any individual season can be an anomaly, but the odd, chaotic weather patterns the country has experienced over the past several years fit the predictions of meteorologists’ computer models. As Bill Selby, our friend who teaches geography at Santa Monica College, said one night over dinner as we discussed this phenomenon, “Oh, there’s a pattern, all right, we just don’t know what it is.”

The pattern is clear to the bristlecone pines: Warmer weather at higher elevations – well above the latitude where these trees are supposed to grow – is creating a nest for the young ones to thrive. That may be good for the trees, but at the current rate of climate change, it doesn’t bode well for humans.

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families