The Heat 2020

Georgia’s Other Runoff Could Weaken the South’s Dirty Energy Monopoly

A utility commissioner backs both Trump and solar energy, but his maverick reputation may not win him reelection. Georgia is changing.

It wasn’t that long ago in Georgia that it was economically pointless to put solar panels on your roof. Not only was there was no net metering law that allowed you to bank your sunshine power as credit, but leasing panels for your rooftop from an installer like Solar City or Sunrun was literally forbidden by law. With Georgia’s low electricity rates, your $30,000 investment in a standalone system might pay for itself eventually, but you might not live to see it.

Co-published by Patch

Nowadays, Georgia ranks among the top 10 states for solar. Between 2013 and 2020, Georgia’s solar capacity shot up exponentially, from a paltry 116 megawatts to 2,664, nearly enough to replace Georgia’s Plant Scherer, the largest coal-fired power plant in the U.S. Much of that involved large installations owned by the utilities themselves, but some electricity providers have also begun to offer net metering to a limited number of customers. Jobs in the solar industry are now growing faster than they are in any other state.

That Bubba McDonald’s seat is threatened at all signifies how much Georgia is changing, and how simply promoting clean energy is no longer enough.

And while environmentalists, business owners and solar lobbyists can all take credit for that expansion, almost all of them will admit it wouldn’t have happened as quickly as it did without a single, unlikely advocate: a Trump-endorsing, hardwired Republican named Lauren “Bubba” McDonald, currently in his second term on Georgia’s Public Service Commission, which regulates most of the state’s utilities.

It was Bubba McDonald who, in 2012, traveled to Germany at the invitation of a private solar company to observe how that country does renewable energy; Bubba McDonald who came home with a plan for Georgia to catch up with Germany’s progress. McDonald even defended Obama-era loan guarantees for solar from what he called “an attempt by Fox News to create another ‘solar scandal,’” back in 2011.

But as he seeks a third term on the commission, the election season has not gone as swimmingly for the anthem-singing octogenarian as he might have hoped. On November 3 McDonald fell just a tenth-of-a-point shy of the 50% state law requires to avoid a runoff; he’ll now face Democrat Daniel Blackman again on January 5 – the same day Georgia voters will determine, in two separate races, which party will control the U.S. Senate.

That his seat is threatened at all signifies how much Georgia is changing, and how simply promoting clean energy isn’t enough. Blackman, who worked with the Obama administration on climate justice and clean-energy access, is well-known in Atlanta and elsewhere for his two-decades of civil rights advocacy. If victorious, he’ll be the first Democrat to win a statewide office in 14 years, and the second black person to be elected to the commission. He has run for the office once before, in 2014, when the public was perhaps less aware of how much the commission mattered.

“The challenge with Georgia for so long is that we have focused on home runs instead of singles and doubles,” he said. State Democrats helped get Joe Biden elected president, but “we haven’t done as good of a job getting local people elected.”

Politics, he said, “shift from the bottom up.”

* * *

Blackman knows that public service and utility commissions, which in the South are mostly elected positions, are almost never the hottest news on voting day. But this year’s race in Georgia could be the rare one that is — and not just because the Senate races will draw attention to the election.

Georgia residents have endured double tragedies in COVID-19 and Hurricane Zeta, which leveled swaths of the Southeast in October and disrupted power for more than a week. But even before that, their utility bills were eclipsing their grocery tabs.

“It’s become a real issue,” Marilyn Brown, a public policy professor at Georgia Tech, told me. “Our cities in particular have a lot of poverty and a high energy burden.” The state’s largest utility, Georgia Power, a subsidiary of the Southern Company that holds much of the South in its monopoly grip, has too often neglected cost-saving energy efficiency in its long-term plans, environmental advocates say.

Georgia residents have endured double tragedies with COVID-19 and Hurricane Zeta. But even before these disasters, their utility bills were eclipsing their grocery tabs.

Shivering or sweltering in their non-weatherized homes, Georgia Power customers pay upwards of $150 for electricity alone; add in natural gas and motor fuel, and their energy bills consistently rank among the highest in the nation, despite relatively low prices per kilowatt hour. Some households spend as much as 20% of their incomes on utilities, Brown said. “What it comes down to is, do you pay your bill or do you feed your kids?”

COVID-19 has put ratepayer pain in dramatic relief. While people were thrown out of work by shutdowns and child-rearing duties, the Public Service Commission placed a moratorium on utility shutoffs. But that expired in July. In two months, more than 40,000 customers lost service altogether in the punishing heat of summer.

Blackman said the commissioners could have made life easier for those customers, but they either declined to act or weighed in on the side of the utilities. A half-billion dollar coal-ash cleanup, the cost of protective gear and other expenses associated with the pandemic, have all been pushed onto ratepayers.

“Decisions were made over the last decade and a half based on profitability and not on the will and best interest of the communities those utilities serve,” Blackman told me.

McDonald declined to comment for this story, but fellow commissioner Tim Echols, himself a renewable energy proponent, defended his colleague. If Blackman prevails, “we lose an elected official with influence in every nook and cranny of the state capitol,” he said. “A new Democratic commissioner would not only have a learning curve but no influence or cachet to get things done.”

* * *

Ironically, McDonald and Jason Shaw were the only two of the five commissioners who actually opposed burdening customers’ bills with Georgia Power’s COVID-19 costs. Both men also voted against allowing Georgia Power to shut off consumers’ power when pandemic restrictions made it hard to stay current on their bills. If critics still hold them responsible for the commission’s decision-making, it’s because they know Georgia politics all too well: Shaw was also up for reelection and barely avoided a runoff with 50.1% of the vote.

“Of course they voted that way,” Brionté McCorkle, executive director of Georgia Conservation Voters, said. “It’s an election year. [The commissioners] know before they sit down at the table where the votes are, and they know they only need three. So why not protect the two that are up for reelection?”

McDonald has been in politics a long time, McCorkle notes; before he became a commissioner, he held office as a state house representative for 20 years. “He’s a very sophisticated operator,” McCorkle said. “He knows how to get people to believe that he’s doing the right thing for them.” (McCorkle is a plaintiff in a lawsuit alleging that the way Georgia chooses commissioners — statewide instead of by district — deprives Black residents in metro Atlanta of representation on utility matters.)

As much as he likes to go to black churches and hand out nail files – common campaign swag in the South – “I would question whether he can posit himself [as] a champion of the people.” His ties to the utilities he regulates are well-known and legion: The Georgia Public Service Commission Accountability Project reports that 85% of McDonald’s campaign contributions were “influence dollars”: They came from individuals or companies affiliated with the industries he’s supposed to regulate. (A little more than 50% of Shaw’s campaign funds came from those same sectors.)

And McDonald has never wavered in his support for Georgia Power’s troubled nuclear facility, Plant Vogtle. For the last seven years, the utility has been in the throes of adding two reactors to the plant’s existing pair, the first of which went online in 1987. Construction began in 2013 with a $14 billion budget, $6.1 billion of which would be paid by the utility, and a 2017 completion date. Now that date has been pushed back to 2022 and the project’s cost has doubled. Georgia Power will be on the hook for $10.5 billion of the projected final $29.6 billion price tag, and those funds are already being collected on every single one of its 2.6 million customers’ bills.

“There’s a line on everyone’s bill that says ‘Nuclear Cost Construction Recovery,” McCorkle said. It’s only five extra dollars at the moment, but for “the people who are nickel and diming, it’s painful to be picking up these costs.” Especially, she added, when everyone knows those fees only go to line shareholders’ pockets, with a 10% return on their investment.

Said Blackman: “We’re going to be paying for that nuclear plant for 60 years.”

One way to lift the utility burden of Georgia’s households would be to expand solar on rooftops and install battery systems in homes. Georgia Power could also efficiency audit and retrofit more buildings. The utility has offered net metering to the first 5,000 customers who apply, “but we don’t yet have 1,000,” Marilyn Brown said. Programs like Solarize, a nonprofit effort that operates as a solar leasing company, has made some gains, “but with electricity rates so low, it doesn’t make sense for companies to come in and rent rooftops. It’s not enough of a revenue stream.”

But all of that is just nicking away at a larger problem, Daniel Blackman argued, which is that utilities “are literally hijacking customers’ pocketbooks.

“If you rob my house and then help me get my stuff back at a cheaper rate, you still robbed my house, right?” A little bit of rooftop solar, in other words, is no consolation for a family buried in utility debt.

McCorkle put it more plainly: “Bubba has been a voice for solar on the commission. I’ll grant him that. But he’s only been a whisper,” she said. “What we need is a roar.”

November 29, 4 p.m.: This story has been revised to include comments from Georgia Public Service Commissioner Tim Echols and to add information about Brionté McCorkle’s participation in a lawsuit against the state.

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

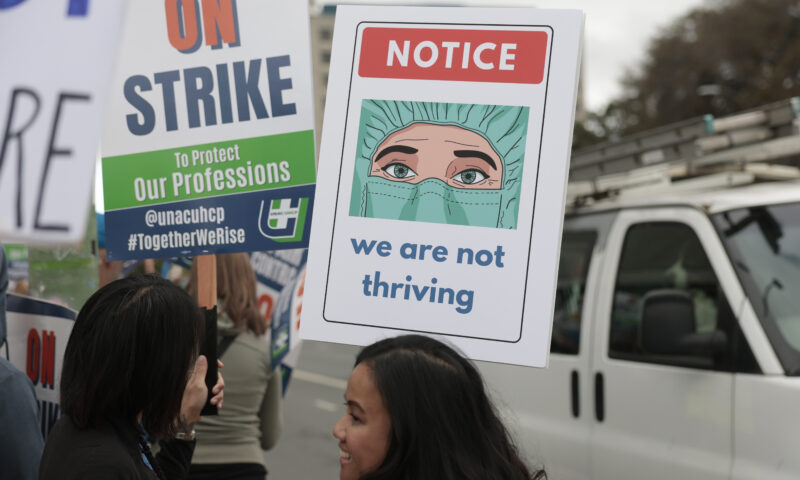

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 21, 2026Honduran Grandfather Who Died in ICE Custody Told Family He’d Felt Ill For Weeks

-

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 22, 2026‘A Fraudulent Scheme’: New Mexico Sues Texas Oil Companies for Walking Away From Their Leaking Wells

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas