Culture & Media

“Gatz”: A Modern Fairy Tale From Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age Classic

There’s an almost childlike thrill one feels watching the early moments of Gatz, the six-hour re-enactment of The Great Gatsby that opened last night at Redcat and which runs through December 9. It comes from listening to an ensemble of committed actors perform every word of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel as though we were being read a fairy tale by our parents. In a way, Fitzgerald’s story about a mysterious man (or is he an ogre?) who lives in a Long Island castle and who pines for a young woman in marital distress is a modern fairy tale. It’s also a Jazz Age fable about soul-destroying materialism, class snobbery and feelings of racial entitlement – which means it also has something for everyone in 21st-century America.

This visiting production, staged by New York’s Elevator Repair Service theater company, has been around in its present form for six years. It is not, I stress, an adaptation of the book, nor a staged reading, but a literal performance of every word printed between its covers. The way it accomplishes this is pure genius. The show begins at some shlubby office, probably in New York, possibly in the early 1990s, when a man (Scott Shepherd) walks in and, after several attempts to boot up a computer, slumps at his desk and flips open a Rolodex. Inside, he finds a paperback copy of the novel, which he begins reading aloud.

“In my younger and more vulnerable years, my father gave me some advice . . .”

So begins this artifact of American Lit classes, albeit delivered in an almost defiantly flat voice by Shepherd, who, however, becomes so engrossed in the book that he cannot stop reading it. Soon he’s doing so with full-throttle emotion – while his colleagues warily stare at him. The man is hooked, both on the book and on the role he now assumes — that of its narrator, Nick Caraway, a young bond dealer who has moved from the Midwest to a wealthy part of Long Island. His neighbor is the enigmatic millionaire Jay Gatsby, who has established himself here to be near his old flame, Daisy.

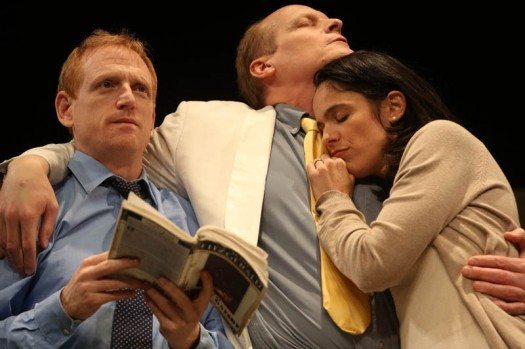

It takes about 20 or 30 minutes before the dozen office workers take on the roles of the novel’s other characters, but when this happens the play transitions from its drab milieu to the novel’s locales, where we meet Gatsby, Daisy, Tom and all the others. These characters still must navigate filing cabinets, typewriters, monitors and desks, but by now they have thoroughly brought us into the novel’s world. (At least they don’t have to carry the paperback with them for their script, as does Shepherd.)

Much of this, of course, is the work of director John Collins, who is responsible for the lion’s share of Gatz‘s concept. Some of the show’s set pieces are unforgettable, especially the drunken party scene that takes place in a Manhattan apartment – a long moment that beautifully captures the dangerous hubris of its revelers and their era. In a cast of standouts, the evening still belongs to Shepherd, a shape-shifter of an actor who, I was told by Collins, has actually memorized the entire novel and could, should he drop the book onstage, continue reciting its lines from heart.

With breaks and dinner intermission, the show runs about eight hours. As far as monumentally long productions go, Gatz is easily a more intellectually rewarding experience than such pop spectacles as Nicholas Nickleby, but not as emotionally challenging as Angels in America or The Kentucky Cycle. That’s because Gatz is often more about itself than its source material. This isn’t to say it doesn’t display an understanding and affection for Fitzgerald’s novel – it does, and Collins’ love and respect of Fitzgerald’s language are obvious.

But so much of Gatz is about its own recurring sight gags, stage business and shtick in general that, after a while, it turns into an inside joke. (ERS has a connective history with the Wooster Group and some of that company’s excessive mannerisms can be glimpsed here.) The Great Gatsby certainly has a martini-dry sense of sardonic humor, but Gatz often seems like one very long gag. Which is why, toward its end, it loses some steam and theatergoers may find themselves staring at Shepherd’s copy of the novel to see how many pages are left.

Gatz, by Elevator Repair Service, Redcat, 631 West Second St., Los Angeles.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit