Culture & Media

Fighting to Protect Others, and Myself

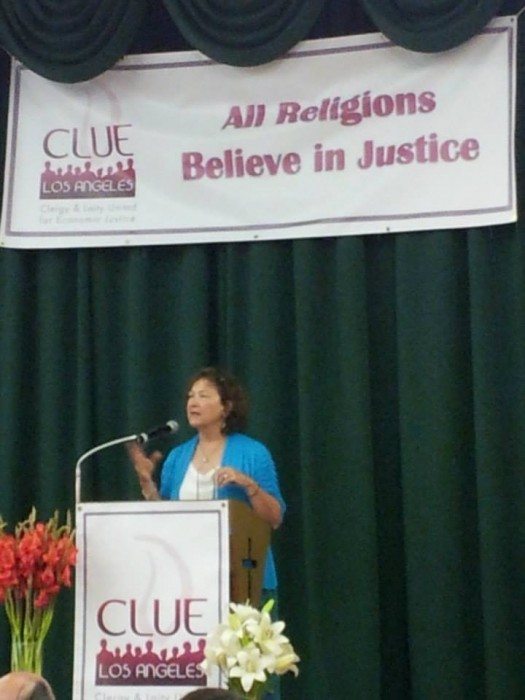

Vivian Rothstein was one of four recipients of a “Giant of Justice” award from Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice Los Angeles (CLUE-LA) last week. She’s a longtime friend and mentor of mine, and was introduced at the breakfast by a longtime friend and mentor of hers, Rev. Jim Lawson. In his intro, Lawson invoked the concept of the “beloved community,” a well-worn phrase whose meaning is often either trivialized or simply lost. So much a part of the civil rights movement from which Vivian’s activism sprung, the idea of a beloved community is what Vivian has imparted to so many of us – that organizing must be rooted in a basic decency and love, and in being so rooted, is transformative well beyond whatever immediate victories, however substantial, may be achieved. We’ve reprinted her speech because it is a such a remarkably well-told story. Not captured here is how it ended, as Vivian, somewhat embarrassed by all the attention and unsure how to respond, stepped back slightly and said, rather sweetly, “It’s been a great life. I highly recommend it.”

– James Elmendorf, LAANE deputy director

Like many other immigrants to the United States, my parents came here to save their lives. My father was a window dresser and my mother was a seamstress. They had grown up in a middle-class Jewish neighborhood in Berlin. As the Nazis came to power, the country started to turn against them, passing laws that restricted Jews from having home gardens, swimming in public pools, having pets, seeing non-Jewish patients if they were physicians, playing to non-Jewish audiences if they were musicians. An opportunity arose to open a business in Amsterdam and my parents took it, leaving many relatives behind. Those who could leave landed in the few places that would have them – Shanghai, Israel, England. One grandmother died in a concentration camp with her sister, the other in hiding with a Dutch family.

After the Dutch Nazi party opened an office next to their store, my parents left for the U.S., sponsored by a relative already here. In those days the only way to get to the U.S. was if someone agreed to support you financially in case you couldn’t find a job. I grew up surrounded by other German Jewish refugees who similarly had lost their families, their homeland and their livelihoods. The world seemed a very dangerous and scary place to me – where inexplicably your country could turn against you, not for anything you ever did, but because of who you are.

Americans didn’t seem to have much understanding of what happened to people in Europe during the war. Even American Jews were pretty ignorant and, amongst some Jews, there was hostility towards German Jews for not “fighting back” – as if fighting against the power of a fascist state was something ordinary people knew how to do. So I didn’t talk about my family’s experience, keeping my feelings to myself.

As a freshman at UC Berkeley, I gravitated towards the civil rights group on campus. These were people who knew the world was hostile and denied them basic rights. Yet they had figured out a way to fight back. I was trained in nonviolent civil disobedience and participated in campaigns for equal hiring opportunities for African Americans at Lucky Food Stores, Sambo’s restaurant chain and the Sheraton Plaza Hotel in San Francisco. Finally I turned 18 and was eligible to join a mass civil disobedience myself, the ultimate show of commitment to fighting the status quo.

The target was the auto dealerships on Van Ness Blvd. in San Francisco, which hired no African Americans in their lucrative sales positions. My group was assigned to the Chrysler dealership. We entered the showroom, I slid under a luxury Chrysler Imperial and went limp. About 400 people in all were arrested along the boulevard, taking the San Francisco police all night to arrest and book us for trespassing, disturbing the peace and failure to disperse.

We were tried in groups of 10, effectively tying up the San Francisco municipal courts for most of the summer. My group was represented by an African American pro bono attorney who presented the history of civil disobedience in the development of American democracy as our defense. During the lunch breaks I was amazed to learn that he was present at the liberation of a German concentration camp while serving in a segregated American army unit. Unexpectedly I’d found someone who deeply understood the experience my family had faced and who was dedicated to fighting similarly racist structures in the U.S. He and I spoke our broken German together and ate liverwurst and pumpernickel for lunch, bringing my worlds together for the first time. I felt acknowledged, safe and courageous all at the same time. And I found my emotional and political home.

For all of us in this room, this movement for economic and social justice speaks to us in a profoundly personal way. Not only does it provide an opportunity to work for the good of people whose lives are filled with hardship, it also provides us with a safe haven and a way to fight for our own safety in a society in which we may feel at risk ourselves. It could be for our religious, racial, ethnic, physical or any other difference that makes us feel separate and apart from the powerful in society. This movement helps us be courageous, to take risks for the common good and to form bonds of trust with people who we feel would fight for us if we need protection. We have the opportunity to be the best people we can be, and also to be surrounded by individuals with compassion and concern.

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care