Culture & Media

Face Time With the Homeless

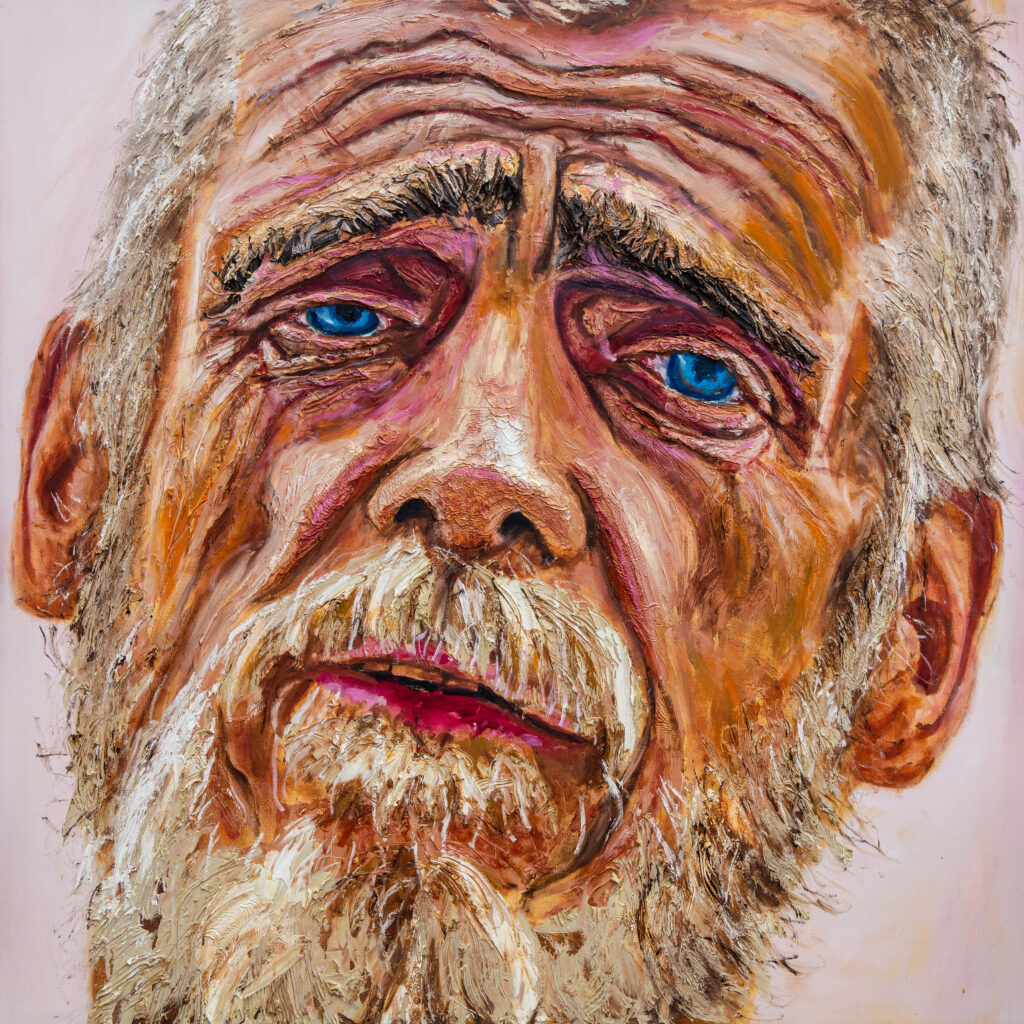

Psychotherapist Stuart Perlman’s portraits capture the humanity of those living on the streets.

Every day, Dr. Stuart Perlman is reminded of the income inequality in this country. For half the week, Perlman the psychoanalyst sees wealthy clients in his private practice. For the other half, Perlman the activist documents the poor and desperate in his Venice neighborhood with a paintbrush.

Perlman, 69, took up painting as a tool for social justice around 12 years ago. As a teen, he realized art wouldn’t pay the bills. So after attending SUNY Stony Brook, the New York City native headed west to UCLA for his doctorate in psychology. After receiving his license, Perlman spent years helping to build programs at various mental health facilities. Budget cuts by Gov. Ronald Reagan, he said, eliminated all of them. So he opened a private practice.

Servicing people of privilege made Perlman one of them. But despite having almost everything he had ever desired, he said he remained unfulfilled. All around his Venice neighborhood, people slept on the streets. He decided to highlight their plight by returning to art.

Over a dozen years later, Perlman has created over 250 portrait paintings, seen in over 60 exhibits around the world. The doctor, who spends 25 hours of each week working from home on homelessness as an artist, has written the book Open Your Heart Through Art: Portraits of Human Souls and Their Life Stories, which was published in October. Perlman recently spoke to Capital & Main about how he came to focus on the very poor as subjects for art.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Capital & Main: How did you get involved with homeless people in your area?

Dr. Stuart Perlman: I’ve lived near Venice Beach since 1975. I’ve seen homeless people around, but I was not really that involved then. I had this very nice upper-class practice in a very nice area, and there [was] a homeless encampment within a hundred feet of my office. And sometimes they would sleep in my doorway, and I couldn’t get in. I started getting angry and yet, at the same time, I got to know a lot of them. I would give them food and clothing. I felt torn between my love of people and my desire to be able to function.

How did that lead to you breaking out a brush and canvas, and how did you get your subjects to trust you?

Dr. Perlman paints a portrait in Venice Beach.

They had the most interesting faces. I was a little afraid at first. It’s very complex to get a homeless person to allow me to use their nicknames, to tell their story, to have details about their life. It’s very exposing and it’s a lot of humiliation and a lot of shame. So it takes a long time for them to trust me. For 12 years I’ve been walking the same streets. A lot I’ve known for a decade, or they’ve known me over the years and seen me paint people.

The thing that I learned is that if you sit quietly with a person comfortably, they start telling you everything. I’ve been a therapist for 47 years, so I naturally start doing therapy. And they tell me all sorts of things. So I would just paint them, and they would talk, I would talk.

There is a lot of despair in the faces. Is this done to underscore your subjects’ predicament?

Yes. But think about someone who’s homeless and what situation they’re in. My goal is to paint the person’s soul and what their emotional state is and what they’re going through. And if a homeless person tells you, “Oh, I’m having a great time,” that’s bullshit.

I understand the vast majority of your subjects are happy with the final product, the sadness notwithstanding.

Yes. You know, one woman who is really very down and out, I told her that her painting had hung in Mayor Garcetti’s office for a year and a half. And she said, “I now feel like I’m something and released from being nothing.”

Do you ever sell your paintings?

I’ve never sold any of these paintings, and people have offered me thousands of dollars for them. So far I haven’t been able to do it. First, they’re my babies. The other thing is I feel like that’s their souls on the canvas. And I also feel that it’s slightly an anti-materialistic statement, like not everything can be bought.

“Jacqueleine” by Stuart Perlman.

And it could be seen as exploitative, right?

Yes. I’m a privileged white guy many times painting a poor Black person or a poor Hispanic, you know what I mean? It’s very complicated. But I also think that this is public art. I’m painting large, you know, five feet by four feet. So it doesn’t go in the nook and cranny in your living room. My goal for these is to get them into decent museums, where they’ll be cared for, where they’ll be seen.

In talking to homeless people, is there a common thread that runs in terms of what puts them on the streets?

A large percentage of homeless people come from situations where the deck was stacked against them just completely. A drug addict mother who sold the kid into prostitution, or didn’t feed them, and they ended up in foster homes where they were sexually abused or beaten or starved. The horror stories of early childhood are very prevalent.

Many of them can get out. But then when things go bad, there’s no one around to help. There are people who would help me if I lost my job and were in a bit of trouble, you know what I mean?

The social network and the safety net in this country is gone. There are hardly any childhood psychiatrists in the county mental health system. Then there are economic issues which have to do with income inequality. If you’re poor, you don’t go to college. You don’t have an education. You don’t have a computer that you can get your classes on. You don’t have internet service. You don’t have a place to study.

“Lauren” by Stuart Perlman.

What do you think is the biggest misconception the public has about homeless people?

We are all just people. And you think you’re safe from being homeless? I have met lawyers. I have met doctors. I have met nurses. I have met commodities brokers. I have met football stars — all homeless because terrible things happen to them. [In my book] Jake was a contractor for big buildings in New York City. He worked on the electrical systems in the Twin Towers and neighboring buildings. He had a wife and kids. He had a house. He had nice cars. He had a boat. And the planes hit the buildings. He was in a nearby building, ran over, and he saw some of his friends jump to their death. He had survivor guilt and just was blown away. He started drinking, taking drugs, lost his wife and children, lost his car and has been wandering. And I met him 18 years later in Venice Beach, still suffering, still upset, still agitated. Things only mean something, if they have a grounding in relationships. And if you lose those relationships, you don’t give a shit.

Homelessness has gotten worse due to the pandemic, which has surely made things tougher on those who were already on the streets. I suspect people are less sympathetic since everyone is under duress to some degree, right?

They’re even more of a pariah. And so many people were afraid of getting COVID, there were a lot of services closed, whole agencies were not functioning. So the homeless were more isolated. They were more alone. There was less hope. And so I think the homeless have gotten more desperate, angrier and more aggressive, more violent. And more suicidal and more destroyed.

“Jake” by Stuart Perlman.

What do you think the future holds for this problem?

I’ve been working in the area of homelessness for 12 years now and I’m a little more pessimistic than I was when I started because people are going to have to make big sacrifices. We really need larger scale changes of attitudes. You need to get to people. You need to help them see homeless people as people. You need to change the laws. You need to fund the programs. You need to change society. I feel like if everybody in the nation can come together around this and make this a central important goal of our society, we could do away with homelessness in 15 years.

And in the meantime, you’ll continue doing your art?

I’m spending most of my time creating products in order to reach millions of people so that I can change attitudes. And if I can change people’s attitudes, all the other things will come.

I can’t live in this world, with all the terrible things going on, unless I do something about it, and I have to do something about it every day or else I feel bad, and I can’t sleep at night. And so when I know that I’ve done this for this person, and I’ve been working on this cause, I can sleep well. Because I am trying.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families