Labor & Economy

Exclusive: Julian Bond on Labor and Civil Rights

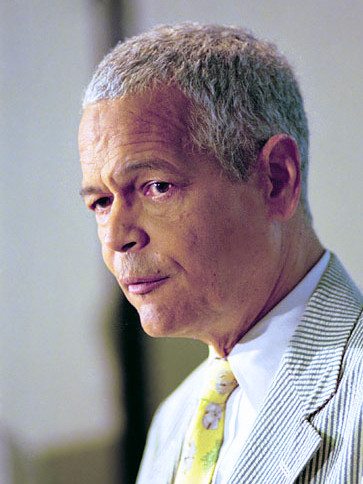

Last month Julian Bond, the pioneering civil rights activist and former Georgia state legislator, addressed an audience gathered in Jackson, Mississippi, to celebrate and analyze the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964. Bond’s speech appears for the first time here, with his permission.

In 1961, when Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the Fourth Constitutional Convention of the AFL-CIO, he spoke of the “unity of purpose” between the labor movement and the movement for civil rights. He said:

[tabs type=[tab_title][tab]“Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.The duality of interests of labor and Negroes [King said] makes any crisis which lacerates you a crisis from which we bleed. As we stand on the threshold of the second half of the twentieth century, a crisis confronts us both.”[/tab][/tabs]

King spoke of “a duality of interests between labor and Negroes,” and he did not mention the undocumented.

If he was speaking today he would.

The crisis he spoke of was and is a crisis for the freedom movement and a crisis for the movement of working women and men. And a crisis for the hard-working millions who want to join us as citizens.

Despite impressive increases in the numbers of black people holding public office, despite our ability now to sit and eat and ride and vote and attend school in places that used to bar black faces, in some important ways nonwhite Americans face restrictions more difficult to attack than in the years that went before.

Labor unions’ membership has plummeted — from 35 percent of workers in the 1950s to about 11.3 percent of the work force today. In 1974 the average American CEO made 34 times as much as the average American worker. By 1995, it was 179 times as much and is higher now – recalling the bitter words of Victor Hugo that there was always more misery in the lower classes than there was humanity in the upper classes.

Those years then were what these years now promise to be — a kind of festive party thrown for America’s rich. Then the middle class had to get by on two paychecks, median family income was stagnant, and the percentage of young families who owned their own homes went down for the first time since the Depression. Savings and investment were down. More Americans were working longer hours at lower pay.

And for those Americans whose skins were black or brown, the poverty rate went up while median family income went down. Poverty for black and Hispanic senior citizens went up, children who were poor got poorer.

In the late 1960s, three-quarters of all black men were working; by the ’80s’ end, only 57 percent had a job.

In l968, the Kerner Commission, appointed by President Johnson to investigate the causes and prescribe the cures for the riots of l967, concluded that “white racism” was the single most important cause of continued racial inequality in income, housing, employment, education and life chances between blacks and whites.

But Lyndon Johnson was succeeded in 1968 by Richard Nixon. He had pursued a “Southern strategy” which used race to leach white voters away from the Democrats.

Republicans have used race as a wedge ever since.

Within a few short years, the growing number of blacks and other minorities and women, pushing for entry into, and power in the academy, the media, business, government and other traditionally white-male institutions, created a backlash in the discourse over race. The previously privileged majority exploded in angry resentment at having to share space with the formerly excluded.

Opinion leaders began to reformulate and redefine the terms of the discussion. No longer was the Kerner Commission’s description of the problem acceptable.

Any indictment of white America could be abandoned, and a Susan Smith defense was adopted — black people did it, did it to the country, did it to themselves. Black behavior — not white racism — became the reason why whites and blacks and browns lived in separate worlds. Racism retreated and pathology advanced. The burden of racial problem solving shifted from racism’s creators to its victims. The failure of the lesser breeds to enjoy society’s fruits became their fault alone. In a kind of nonsensical tautology we heard again and again: These people are poor because they are pathological, they are pathological because they are poor.

Just as the movement King led began to win access for black workers to industrial jobs and organized labor, the jobs went offshore and labor declined in power and influence.

Forgotten [amid] the modern wave of inaugurations of new black majors was the plight of blue collar blacks; plans to use the market system to revive the ghetto were embraced by a generation of politically connected black entrepreneurs, and their cause gained ascendancy. Black elites joined white elites at the feeding trough.

We’ve all seen the results – the national nullification of the needs of the needy, the gratuitous gratification of the gross and the greedy, the practice of the politics of impropriety, prevarication, pious platitudes and the triumph of self-righteous swinishness.

Once again, King’s words, delivered three-and-a half decades ago, speak to us today. He said then,

[tabs type=[tab_title][tab]”Differences have been contrived by outsiders who seek to impose disunity by dividing brothers because the color of their skin has a different shade. I look forward confidently to the day when all who work for a living will be one with no thought to their separateness as Negroes, Jews, Italians or any other distinctions.”[/tab][/tabs]

King lost his life supporting a garbage workers’ strike in Memphis; the right to decent work at decent pay remains as basic to human freedom as the right to vote.

King isn’t the only soldier missing from the Freedom Fight. He didn’t march from Selma to Montgomery by himself; he didn’t speak to an empty field at the March on Washington. There were thousands marching with him and before him, and thousands more who did the dirty work that preceded the triumphant march.

Black Americans really didn’t just march to freedom and we didn’t march alone. We worked our way to civil rights through the difficult business of organizing: knocking on doors, one by one. Registering voters, one by one. Creating a community organization, block by block. Financing the cause of social justice, dollar by dollar. Building a statewide movement, town by town. Creating an interracial coalition, nationwide. We marched with an army of people who did not look like us, but we welcomed them to our side.

Yesterday’s movement succeeded because the victims became their own best champions. When Rosa Parks refused to stand up on a Montgomery bus, and when Martin Luther King stood up to speak, mass participation came to the movement for civil rights.

In the same way, the labor movement was built on sacrifice, hard work and organizing.

What we did in the civil rights movement was tell the truth. William Cullen Bryant was right when he said, “Truth crushed to earth will rise again.” And James Russell Lowell was right when he declared:

[tabs type=[tab_title][tab]”Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne, yet that scaffold sways the future, and behind the dim unknown, stands God within the shadow, keeping watch above His own.”[/tab][/tabs]

We must get back to the difficult business of organizing, of creating coalitions, keeping watch above our own.

We can achieve grander victories — but not without greater efforts, keeping truth forever on the throne.

When I entered the labor force more than five decades ago, there were five workers making contributions into the Social Security System — the public pension system — for every retiree.

We can’t tell who they were, but their names were likely Carl, Ralph, Bob, Steve and Bill.

When I retire, there will be only three workers paying into the system for every retiree — their names may well be Kwanza, Maria and Jose.

America needs to insure – we need to insure – that they have the best futures, the best education, the best health care, the best jobs and schools we possibly can.

(Julian Bond was Chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s board of directors from 1998 until 2010, and is now Chairman Emeritus. He is a Distinguished Scholar in the School of Government at American University in Washington, D.C., and Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Virginia.)

Julian Bond photo by Jim Wallace

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families