Environment

Don’t Look Away: Dr. Peter Kalmus on the United Nations’ Latest Climate Report

Kalmus, a climate scientist and activist, explains why we need to act now, and fast, to forestall calamity.

Dr. Peter Kalmus looks like a taller, fitter version of Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, Dr. Randall Mindy, in Netflix’s Don’t Look Up, last year’s climate change movie masquerading as a comet-cataclysm movie. Like DiCaprio’s character in the film written and directed by Adam McKay, Kalmus is also a scientist warning humanity of an impending global calamity, to little effect.

But when asked about the similarities, Kalmus says he feels a stronger kinship with the Ph.D. student played by Jennifer Lawrence: “She is just tirelessly sounding the alarm, and she can’t believe that the people around her don’t get it and are ignoring her.”

“It’s a very uncomfortable place,” he said, “being that Cassandra.”

Kalmus is a physicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains north of Los Angeles. For years, he studied clouds and how they affect climate models. Now he studies a trio of climate change responses: changes in the oceans’ coral reefs; the last two decades of severe convection over the U.S. Midwest; and extreme heat over the world’s major cities.

When not studying climate systems, he writes books, and has made a documentary — Being the Change: A New Kind of Climate Documentary — about the impending climate disaster and how that drove him to change how he lives his own life.

Kalmus doesn’t fly. He bikes wherever he can, and when he can’t, he drives an EV. His previous car ran on used vegetable oil. His front yard has no grass. He composts his own poop. His lifestyle, he says, emits about one-tenth the amount of carbon as the average American.

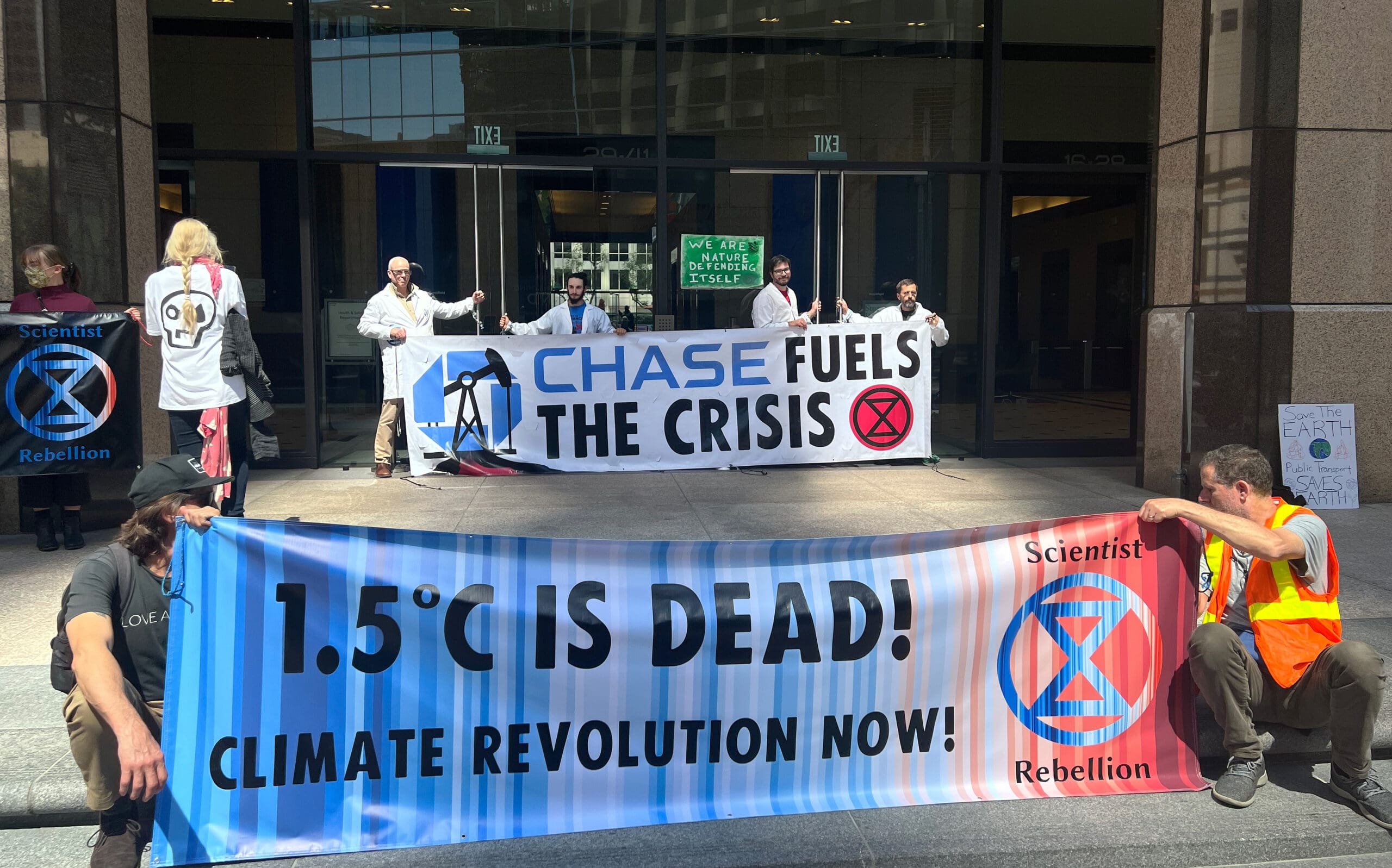

And two days after the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on mitigating climate change came out on April 4, Kalmus locked himself to the door of the JPMorgan Chase building in downtown Los Angeles. He demanded that the corporation stop financing fossil fuel projects — an act that got him arrested.

Capital & Main asked Kalmus for his take on the latest United Nations report and other climate matters. He agreed after making it clear that these are his own opinions and he was not speaking in any way on behalf of NASA or JPL. The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

Capital & Main: You brought up being a Cassandra. That must be a very uncomfortable position to be in all the time. How does that feel?

Peter Kalmus: I have a really complicated mix of emotions. And some of them come up and become dominant at different times. But I feel frustration. I feel fury. I feel grief, quite often.

Sometimes I feel anxiety — I’m not sure if that’s really an emotion. And I have practices, personal practices that I do to keep the anxiety at bay, because I find it can get very debilitating.

Sometimes, I feel a sense of surreality. And to me, that surreal aspect has a lot to do with the irreversibility of Earth’s breakdown. There’s not words to describe it, really. So, “breaks my heart” is probably the closest about how beautiful this planet is, and how precious it is, and we’re losing this. And it’s irreversible. I don’t think the public grasps that irreversibility.

“One of the things you get by reducing your emissions is a very clear sense of those systems that surround us that need to change.”

Once you understand that we’re in the process of losing everything, your career doesn’t seem very important anymore at that point. So, the barrier to speaking out dissolves, the barrier to risking arrest dissolves, because you realize that what’s at stake is so much bigger.

There’s something holding back a lot of my colleagues and it’s been holding them back for a long time. And I’m honestly not entirely sure what it is. But I think it’s fear of breaking social norms, and it’s fear of losing one’s job and possibly it’s a fear of being ostracized. Maybe it’s a fear of not getting awards and not getting recognition, because it’s a rocky path to be a Cassandra.

But, you know, the fear of losing the Earth for me is just so much bigger than all those things. That kind of emotional calculus is very clear for what I need to do. It’s not even like a choice that I struggle with.

Let’s go to the IPCC report, which is all about mitigation, which seems to be totally up your alley. That’s what your whole public life has been for the last several years — it seems you’re leading a life of mitigation and then trying to get other people to do that as well. Do you think that’s a fair comparison?

You know, I don’t think that my own actions — like my efforts to reduce my own emissions — were very impactful. But I don’t regret them for a second. And I think it’s a great thing for anyone to reduce their emissions.

I’ve been a little bit surprised at how many climate activists find that point of view sort of toxic, because, to me, it’s just very natural. If you’re a climate activist, from my perspective, you should probably want to try to reduce your emissions. But I think it’s also important to balance that. I still do use some fossil fuels. It’s almost impossible, given the systems that we live within, to eliminate all of your fossil fuels. I don’t know a single person who’s done that.

One of the things you get by reducing your emissions is a very clear sense of those systems that surround us that need to change.

“I think we’re in a situation in real life — right now — which is, if anything, more striking and more dissonant than in Don’t Look Up.”

I feel disgust at fossil fuel in all of its aspects in every scale. I don’t want that to be part of my life. I mean, fossil fuel literally is death, and the public hasn’t realized that. But from the climate-science point of view, it’s a completely direct relationship.

The IPCC Working Group III report, I think, more clearly than ever before, makes that connection at the largest scale — at the planetary scale. And part of the reason I decided to engage in civil disobedience is because there’s the disconnect between the science and the scientific core consensus messaging, and what world leaders are actually doing in response to that. That gap is getting bigger — it’s not getting smaller, it’s getting bigger. And that makes me feel desperate.

It’s not just the scientific facts that are leading me to acts of civil disobedience: It’s the combination of the scientific facts and the complete lack of action by world leaders. And not only the lack of action, but the fact that they are bending over backwards, doing everything they can to expand the fossil fuel industry at this point in the climate emergency.

I think we’re in a situation in real life — right now — which is, if anything, more striking and more dissonant than in Don’t Look Up.

Kalmus and fellow protestors outside of JPMorgan Chase. The action was one of several climate protests throughout the world by a group of concerned scientists called the Scientist Rebellion. Photo: Brian Emerson.

Speaking of political dissonance, New Mexico (a focus of Capital & Main’s oil and gas coverage) is the second largest oil-producing state in the United States, and is also one of the least developed and the poorest. But it depends heavily on oil and gas revenues to fill about 40% of the state budget. It’s a dangerous conundrum to be at the cutting edge of actual climate change, which you can see there every day, and at the same time be dependent on oil and gas revenue. How do you see decarbonizing a place like New Mexico?

I think New Mexico is one of the best states in the country for generating solar electricity, right? So, I think transitioning away from the fossil fuel economy, in terms of jobs and possibly state revenues, should probably be a very easy sell.

You know, energy is energy. And you should be able to have some level of prosperity around the build-out of renewables, which we desperately need. It’s kind of more a lack of imagination to have that perspective that “Well, we depend on fossil fuel revenues. So, therefore, we were going to choose those revenues over having a livable planet.” Right? And they can’t see it. It’s a lack of imagination to not see that the transition could be an economic opportunity at the same time.

I’m a climate scientist, you know? I don’t know too much about how the state government of New Mexico should specifically orchestrate that transition. But it’s a deadly short term-ism to put fossil fuel revenues over having a livable planet.

Let’s take a quick step back to the IPCC report itself. What did you see? Did you think there was anything missing from the report? And if so, what?

Every day of inaction is going to lead to more death, suffering and irreversible consequences. Like, that’s super clear in the report. So, we should be examining our use of energy overall.

This kind of luxurious, high-energy life, lots of flying in planes, lots of SUVs and McMansions and living really far away from work and living far away from loved ones … we have to weigh those things against all the wildfires and massive droughts and coming agricultural failures and flooding and loss of coastal cities and decide which one we think is more important. Is it eating beef and flying in planes or is it stopping the loss of the world’s coastal cities and coral reefs and forests?

I was really unhappy to see the report still talking about carbon direct capture [capturing carbon dioxide from the air and sequestering it underground], which I think is scientifically irresponsible to include.

“There’s a whole school of thought that says we should sugarcoat this because we don’t want to scare people too much. I think that’s absolutely the wrong approach.”

It’s not something that we have now; it’s not something that we may ever have at scale. We can build plants that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but they require a tremendous amount of energy, because you’re running basically an energy-releasing reaction in reverse. To do that at the scale of 60 billion tons a year or more would be so tremendously expensive.

The assumption that our kids will do that, like 20 or 30 years from now, when they’re fighting, potentially, wars over water and they’re dying by the millions in their cities because of the heat waves that we’ve left them. I could talk for hours about all the stuff our kids are going to be facing. To expect them to pull our carbon out of the atmosphere at tremendous expense — and it might not even work — I think that it’s actually unethical to include that in the IPCC report.

I think the reason that was put in there originally is because it’s such an awkward position for the authors, too. They’re kind of caught between a rock and a hard place where they know the scientific facts and how bad what’s coming is going to be. And they fully realized that the only real solution is to end the fossil fuel industry as quickly as possible. And yet, they have policymakers that love the fossil fuel industry, and want to expand it and need to have low gas prices so that they could get reelected. And so, they came up with this really horribly irresponsible mechanism for dealing with that rock and that hard place, which is this fantastical technological panacea that would magically pull carbon out of the atmosphere. So that, to me, was the low point of the report.

Do you have any bright spots that you see in the research that you’re doing or any sort of hope going forward? Where do you see the possibilities?

I’m actually a pretty happy person overall, I think. I just happen to see something extremely worrisome, and I’m trying to warn people about it and then change course. If I didn’t have hope I wouldn’t be fighting so hard to make change.

But, you know, every day we wait, it’s a little bit grimmer and we’ve lost a little more. It’s just a fact.

There are a couple of really nice bright spots in the IPCC report. One is the incredible progress in terms of the cost of solar, wind and battery storage. We were talking about the New Mexico economy, right? It’s this huge thing, like “Ding-ding-ding!” This is what we should be doing. It’s already cheaper than natural gas electricity in almost every market.

The reason we haven’t been adopting it quickly enough is because of vested interests who make money off of fossil fuels. And because we’re locked into fossil fuel infrastructure, which was another really important point that the IPCC report makes. You have these fossil fuel projects that last, on average, almost 40 years. It’s madness if we build new ones now. It’s either stupidly stranded assets that we have to shut down in a couple of years, or it brings us to planetary destruction. So, it’s absolutely foolish to build new fossil fuel infrastructure.

The report made it really clear that globally, we need emissions to peak in the 2020 to 2025 time period, which we’re literally right in the middle of right now. And that’s to try to still avoid two degrees Celsius of global heating, which I personally think is going to be absolutely catastrophic. I don’t think people understand how bad two degrees Celsius global heating really is going to be.

There’s a whole school of thought that says we should sugarcoat this because we don’t want to scare people too much. I think that’s absolutely the wrong approach. If the public becomes terrified of what they should be terrified of, then they will make stopping it their top priority.

So once that happens and it’s humanity’s top priority and we actually start trying, I think we could stop the damage really, really quickly.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.