Culture & Media

Dick Gregory: A Stand-up Activist

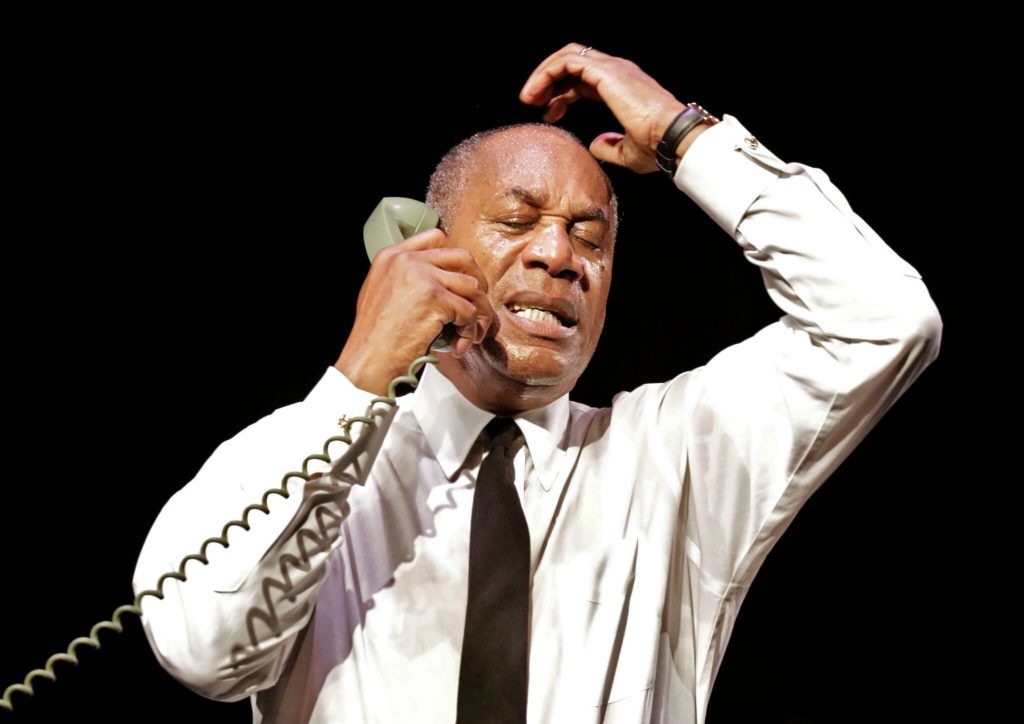

This illuminating stage work about Dick Gregory, the late iconic comedian and civil rights activist, receives a powerhouse performance from Joe Morton as the stand-up comic.

Joe Morton as Dick Gregory. (Photos by Lawrence K. Ho)

Before Dick Gregory, black entertainers weren’t allowed to sit on the Tonight Show ’s couch. A talk with Gregory and Jack Paar changed that.

In his powerhouse performance as Dick Gregory, the stand-up comic who rose to fame in the 1960s, Joe Morton tells the following story: He was civil rights organizing in the South with his good friend Medgar Evers, when he received a call informing him that his infant son had died. Gregory packed up and went home to comfort his grieving wife. Two weeks later a white supremacist shot down Evers in his own driveway as his family watched — an end, reflects Morton’s Gregory, that might have been his had not fate intervened.

The anecdote is one of many that emerge in Gretchen Law’s Turn Me Loose, an illuminating work about this iconic comedian who passed away last August at age 84. Directed by John Gould Rubin, the play shifts back and forth from the 1960s, when Gregory was a trailblazing black entertainer — widely regarded as the first African-American comic to successfully perform before both black and white audiences.

Turn Me Loose isn’t a chronological narrative, but we do learn about Gregory’s background, confided to us in the course of his stand-up routines. Born dirt poor in Alabama in 1932, he grew up exposed to racism at its rawest: When he was 10, he had two front teeth knocked out for touching a white woman’s leg. (He was shining shoes.) He made it to college by dint of skills as a runner, but left before graduating to pursue his career as a stand-up. Hugh Hefner spotted him and gave him a gig at the Playboy Club, where he performed before groups of white Southerners who heckled him viciously, shouting out “nigger” and other epithets. In the play, reminiscences like these are vividly re-enacted, with supporting actor John Carlin (spot-on in multiple roles) depicting these bigots with frightening credibility.

The play also highlights a turning point in Gregory’s career when, in 1961, he was invited to appear on the Tonight Show with Jack Parr. At the time, black entertainers might be invited to perform, but they were never permitted to “sit on the couch” with the host and chat as equals. On principle, Gregory refused the invitation numerous times — even hanging up on some of the calls. One particularly intense scene re-imagines Gregory’s frenzied frustration at turning down an opportunity that might change his life. In the end Parr personally called, and after the two men spoke, Gregory became the first guest of color to sit on the couch.

Some of the mid-20th century riffs are a “blast from the past” and not in a good way: They take you back to when racism was everywhere crude, overt and systemic, and the threat of violence was ever present. But these same elements underscore the courage of this smart, talented man who put himself out there, on the theatrical stage and the public one. The play actually becomes more powerful when it draws away from Gregory the entertainer to Gregory the activist and thinker, who warns us that our focus on Middle Eastern terrorists or on political skirmishes based on religion or ethnicity are merely distractions foisted on us by powerful oligarchs who stand to gain from our squabbling.

Morton is just terrific: Beautifully paced by Rubin, his portrayal is an uplifting tour de force that begins modestly and gradually grows more emotionally encompassing. His physical energy is inspiring. As Gregory, his moments of rumination on the death of Evers are especially moving. Reportedly, Evers’ dying utterance was “Turn me loose” — an apt title surely for Law’s play about someone who told it like he saw it, and held nothing back.

Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills; Thurs.-Sat., 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun., 2:30 p.m.; (310) 746-4000 or TheWallis.org/TML; through Nov. 19.

-

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026

The SlickJanuary 23, 2026Yes, the Energy Transition Is Coming. But ‘Probably Not’ in Our Lifetime.

-

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026

The SlickJanuary 27, 2026The One Big Beautiful Prediction: The Energy Transition Is Still Alive

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care