Politics & Government

Dark Money, Honey: How a Koch Ring Got Busted

Last week’s announcement of a settlement between the state of California and two political campaign organizations linked to the Koch brothers fittingly coincided with the centenary of the first scientific explorations of Los Angeles’ La Brea Tar Pits. The history of the tar pits is pretty straightforward: For at least 38,000 years, thick, petroleum-based asphaltum has oozed up from fissures at the site, a noxious goo that long ago entrapped hapless animals as well as the predators that tried to feast on them.

Rather more recent and less explored have been the political intrigues of petroleum tycoons Charles and David Koch, although news of their ambitions is slowly rising to the surface, too. Last year a daisy chain of groups with Koch connections funneled campaign contributions into a pair of policy measures on the 2012 California ballot: Proposition 30, a tax-raising measure designed to restore much-needed funds to public education, and Proposition 32, an attempt to curtail the ability of labor unions to raise political money from membership dues.

The brothers, who are not California residents, were dead against Proposition 30 and all for Proposition 32. Campaign filings with the state’s Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) and a lengthy deposition conducted by the commission of Republican operative Anthony Russo provide hints of just how much so. Here is a brief rundown of events:

- By Labor Day, 2012, the conservative activists who were fighting Prop. 30 and backing Prop. 32 under the umbrella name, California Comeback, had amassed a huge in-state campaign war chest. Millions had already been spent setting up political action committees (PACs) and advertising focus groups. Yet $29 million in contributions remained with the Virginia-based Americans for Job Security. And AJS had a headache: Would California’s Political Reform Act require it to publicly disclose the names of its 150 well-heeled donors (including construction mogul-philanthropist Eli Broad, super-investor Charles Schwab and Gap chairman Bob Fisher) once their money began to be spent on advertising? The campaign groups agreed upon a workaround: AJS would send $25 million to California by way of several out-of-state money drops. The main conduit would be the oddly named Center to Protect Patient Rights (CPPR), a conservative Arizona nonprofit whose president, Sean Noble, has ties to the Koch brothers. From CPPR the money would be bounced to another Arizona nonprofit, the more prosaically titled Americans for Responsible Leadership (ARL) and to the Iowa-based American Future Fund.

- On September 11, 2012, CPPR sent $7 million of AJS money to AFF, which then forwarded $4.08 to a freshly minted California Future Fund for Free Markets. In October CPPR sent $18 million to ARL, which in turn sent $11 to the Small Business Action Committee (SBAC) — the California PAC at the heart of the two conservative ballot campaigns. But this last donation raised red flags at the FPPC. Commission Chair Ann Ravel demanded that ARL reveal the source of this money. At first ARL tried to stall, but quickly found itself being sued by the FPPC and the California attorney general’s office to cough up names. By Election Day, ARL and CPPR would roll on AJS, naming the Virginians as the source of the out-of-state money that eventually ended up in SBAC’s coffers.

- Following the disclosure, the offices of Ravel and state Attorney General Kamala Harris conducted a joint investigation into the money’s sources. The FPPC and attorney general charged the CPPR and ARL with failure to properly disclose their donors, and fined each group $500,000. SBAC and AFF, however, were ordered last week to hand over $11 million and $4.08, respectively, to California under the “disgorgement” provision of the state’s Political Reform Act.

The October 24 FPPC press release announcing the settlement minced no words, claiming that the “two nonprofits operated as part of the ‘Koch Brothers’ Network’ of dark money political nonprofit corporations.”

It is perhaps, however, a measure of how much contemporary political funding resembles a horse auction that nearly none of the money transfers involved in this scheme violated any election laws. CPPR and ARL were busted on the relatively minor technicality of failing to disclose the names of donors. Both the attorney general’s and FPPC press statements claimed that the Arizonans’ missteps were not considered intentional, and charitably ascribed them to their unfamiliarity with California’s election codes.

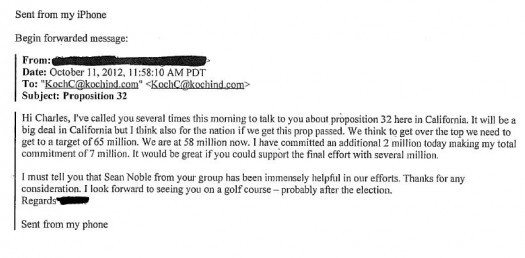

Although California Comeback Kid Anthony Russo believes the Koch brothers’ own personal money went directly into his group’s two campaigns (see his email to Charles Koch, in which Russo breezily suggests, “It would be great if you could support the final effort with several million”), a Koch spokesman has denied this. Of course, the Kochs are too smart to leave their fingerprints on this kind of donation, and with good reason – the election-eve news of the brothers’ possible involvement helped rally votes against their causes.

This has left their less sophisticated agents holding the bag. A look at SBAC’s IRS Form 990 for the year preceding the election shows the group claimed assets of $296,907 at the end of 2011. SBAC’s president, Joel Fox, also edits the conservative Fox&Hounds political blog, which predictably protested the disgorgement order. Most of that money, after all, was spent on last year’s campaigns, says Fox.

“We were not given the opportunity to explain that we believe the FPPC has completely misapplied the disgorgement law in this case,” wrote Fox, who by now must be feeling like one of those trapped animals seen in La Brea Tar Pits dioramas. SBAC struck a defiant stance and says it will not pay the disgorgement money, while American Future Fund has not commented on the settlement. When contacted by Frying Pan News for comment, Gary Winuk, FPPC’s chief attorney in its Enforcement Division, did not spell out the commission’s plans.

“We have sent them a notice that the disgorgement is due,” Winuk emailed. “If no payment is received we will consider future actions at that point.”

One very interesting comment Russo made to his interrogators points to a new appreciation among California conservatives that Republicans are in a shrinking minority in this state and that moneyed interests must find other ways to influence public policy beyond relying on the GOP.

“The party wasn’t particularly effective or even an opposition anymore,” Russo explained to state attorneys. His group, he said, thought “we should look to other models to see if we could create pressure for reform.” Russo added that he and his friends were impressed by the effect of Koch money in Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s successful campaign to strip state employee unions of their collective bargaining rights.

In the end, the record $1 million in civil fines – and, if the state can collect, the $15 million in disgorgement money – is going to California’s general fund. While the money represents a parking ticket to the Kochs, it could well end up benefiting the state’s school children – the very people the brothers had hoped to deprive of a better education.

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.