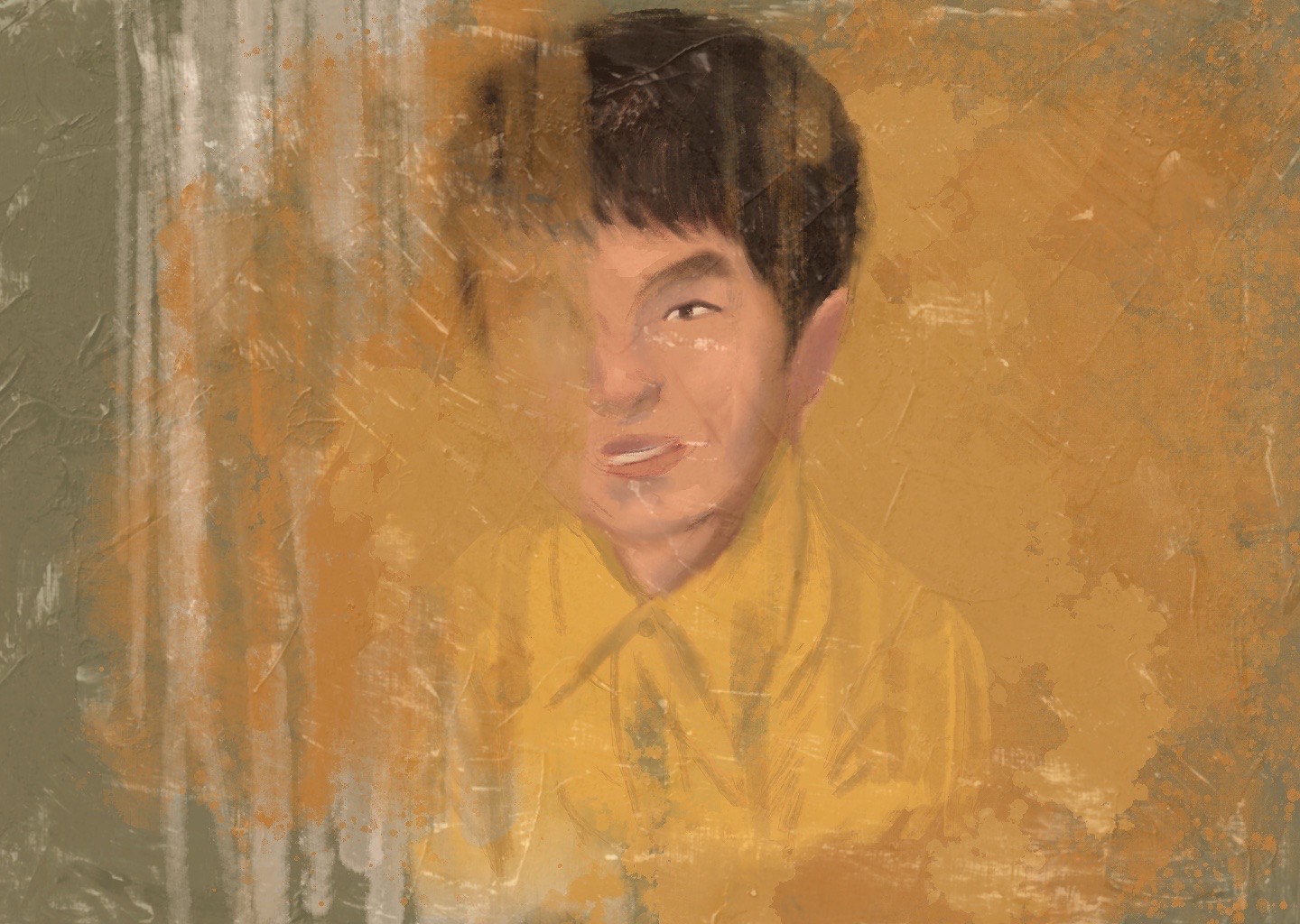

California Poet Laureate Lee Herrick on how poetry became a weapon against hate and erasure in the face of COVID-era attacks on Asian Americans.

In “Poets on the Beat,” a collaboration between Capital & Main and the Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, distinguished California poets provide new perspectives on such topics as climate change, inequality, the immigrant experience and police violence.

Long before I was appointed California poet laureate, I was born in Daejeon, Korea. When I was almost 1, I was adopted to the United States and arrived at the San Francisco International Airport, where I became Lee Herrick.

As an Asian American boy growing up in Modesto in the 1970s, I experienced racism on a regular basis. I felt it on multiple levels: mockery, ridicule, erasure, bullying. I was told, “Go back to China.” Classmates made karate moves at me. They pulled their eyes back and bowed in my direction. At home, I was the only Asian, and while I was raised in a loving and supportive home, my race and culture were an afterthought at best. In school and in the media, it was erasure after erasure until I was almost erased.

Many years later, when I wrote the poem “My California,” I remember thinking that even though I grew up mostly feeling like an outsider, this state was undeniably my own. In that recognition, I felt that I could stand up for myself and others, and begin to take part in shaping the state, and a world, that I want to live in.

Here, in my California, everywhere is Chinatown,

everywhere is K-Town, everywhere is Armeniatown,

everywhere a Little Italy. Less confederacy.

No internment in the Valley.

Better history texts for the juniors.

In my California, free sounds and free touch.

Free questions, free answers.

Free songs from parents and poets,

those hopeful bodies of light.

This poem reflects the California I want to live in. But the state, for all its bounty and opportunity, has a dark history of racism against people of color, including against people of Asian descent. That past still haunts our present, a fact that became painfully clear in the early days of COVID as President Trump used inflammatory language to discuss the virus’s origins. In 2020, hate crimes against Asians in California more than doubled; the most common type of anti-Asian hate crime reported was violent crime. A 75-year-old man died after a robbery in Oakland, and then, in June 2021, a 94-year-old San Francisco woman was stabbed. Hate crimes against Asian Americans in California surged 175% in 2021 from the previous year to 247.

In this context of despicable hate and violence, poets joined policymakers and organizers in speaking out. They also turned to the page. The poet Maxine Hong Kingston instructs, “In a time of destruction, create something.” The poems created and shared during that time became weapons against hate.

In 2021, Sherry Cola, a stand-up comic and future star of the popular film Joy Ride, turned to poetry after eight people were gunned down in Atlanta, six of them of Asian descent. With a tight camera frame, she performed a rhyming poem with a controlled rage that reflected how many felt at the time. “[S]top ignoring these crimes and playing pretend,” she urged. “Let’s have each other’s backs and put this hate to an end.”

In another poem written during peak COVID, Bao Phi, a poet from the Twin Cities, Minnesota, area, imagines an alternate reality, a world where “bigots are too busy with therapy to pay us any mind.” His poem “Alternate Reality, or, A Narrow Opening” was published on Unmargin, a website that provides an Asian American perspective on social justice issues.

Instead of a grandmother kicked in her face:

a thousand orchids blooming from each swinging foot,

the stems and petals forming a fragrant facemask wrapped around every face –

hers, and yours.

Instead of a man and his child stabbed in the face,

the knives turned to pens,

sentences flowing like blood as the story of their lives filled the body of flag after flag,

embracing the wind from every direction….

Instead of you chinks brought the virus here,

there is a chorus in a language no one understood but translated as beauty,

so loud you were shaken,

and you learned the limitations of dancing how you’ve always been taught to dance.

Mia Soumbasakis, a student poet and performer at UC Berkeley, told me that poetry allows Asian American artists to “voice their grief and agitation,” build community with one another and “expose the systemic and imperialistic roots of these acts of violence.”

Since 2021, the number of recorded hate crimes against Asian Americans has declined across the state, but some in the community fear that crimes are going unreported.

“We internalize a lot of things, and unfortunately, we’re not reporting, and we’re getting into the habit again,” Hong Lee, president of Seniors Fight Back, a Torrance-based organization that organizes self-defense classes for seniors, told the Los Angeles Times in July.

Lee is talking about the dangerous habit of remaining silent.

Kundiman, a literary organization, curated 10 Asian American poems of protest in April 2020. One of those poems was Timothy Yu’s “Chinese Silence No. 22.” In this satiric work, he challenges the stereotype of the silent Asian American, a “Silence that by No Means Should Be Mistaken for Bitterness.” His antidote: “a really loud wall….”

I mean a noisy wall of language

that dwarfs my medieval battlements

and paves the Pacific to lap

California’s shores with its brick-hard words.

With those brick-hard words, Asian American poets, like poets from all other backgrounds and walks of life, remind us that we are here, that in times or grief or times of grace, we have the right to dignity, safety and joy like everyone else.

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main.