Culture & Media

Baseball: My Mother the Feminist Would Never Drop a Ball on Purpose

My mother and aunt were two of the girls of summer, recruited by the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League to play pro baseball during World War II. Twenty-five years ago this month, the league became famous when the film, A League of Their Own, became a hit. BY KELLY CANDAELE

Helen Callaghan, the author’s mother

My mother and aunt were two of the girls of summer, recruited from Canada by the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League to play pro baseball in the 1940s as the United States sent many of its best male ballplayers to fight in World War II. Twenty-five years ago this month, the league became famous when the Columbia Pictures film, A League of Their Own, starring Tom Hanks, Madonna and Geena Davis, became a home-run comedy hit. A few years prior, I had produced a PBS documentary film of the same name about my mom and aunt’s years in the league that was the inspiration for the feature movie.

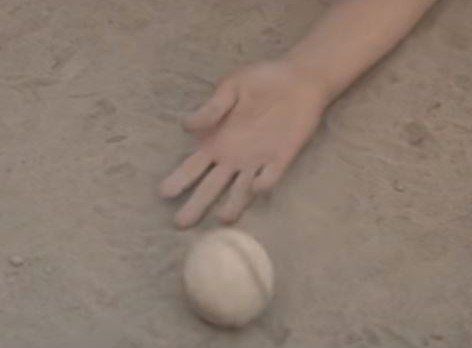

People still ask me questions about the film that usually start with, “Did you meet Madonna and Tom Hanks?” and end with, “Did your mom drop the ball on purpose at the end of the movie to let her younger sister win the game?” In the Penny Marshall-directed film, Dottie, a great hitting catcher played by Davis, drops the ball when she is run over at the plate in the last inning by her sister Kit, played by Lori Petty. Kit’s team wins the World Series and the sisters finally reconcile after spending most of the film squabbling in ways that only siblings can.

One writer recently observed about that crucial scene that “the internet is filled with painstaking did-she-or-didn’t-she analyses” about the dropped ball. Thousands of movie and baseball fans have weighed in over the years, some arguing that Dottie boosted her sister’s confidence by “letting her win,” with others asserting that the film’s “narrative arc” clearly dictates that Kit must win the game fair and square.

In my household the answer is simple: My mother – who passed away the year the film came out – would never have dropped the ball on purpose to let her sister win. No way — not a chance. And there are good moral, psychological and even philosophical reasons for why.

Dropping a ball on purpose to let a relative or friend win a game is a betrayal on several levels. It is a betrayal first and foremost of your teammates, who are fighting hard to win the game and expect that you are doing the same. It is a betrayal of your own integrity, assuming that you have a clear understanding of what constitutes fair play. Letting someone win is also condescending, retaining for yourself the power to determine the other person’s fate, thereby denying them any unmitigated satisfaction. And purposefully losing a game is a betrayal of both the game itself and the spectators.

As social critic Christopher Lasch pointed out in The Culture of Narcissism, watching those who have mastered a sport can provide exacting standards by which we can measure ourselves. There is an “illusion of reality” that players and spectators participate in by accepting the rules and rituals of the games they play. What should bind the spectator and the athlete, Lasch writes, is recognition of this “representational value” of serious athletics when not degraded by spectacle or trivialization. If someone drops a ball on purpose or misses a basketball shot intentionally, whatever positive symbolic value sports might have vanishes.

My mother was an athletic warrior who took her baseball skills seriously. She was fiercely competitive, driven to win and, like many great athletes, was capable of a measure of anger against her opponents.

A lot of anger is expressed in the movie. The sisters fight about whether one of them is receiving special treatment from team owners. The players express their appropriately targeted anger towards their manager (Hanks), who refuses to recognize them as gifted athletes. “I don’t have ballplayers, I’ve got girls,” he says early in the film.

And when the male team owners tell the women it’s time to go back home and into the kitchen, they band together in sisterly and class solidarity to save their league. (My mother worked in an armaments factory before joining her team, the Fort Wayne Daisies.)

My mother understood that anger, when properly expressed, is a form of self-assertion and can transform relationships with others in positive ways. This is especially true on the baseball diamond, where an intensity of effort can overcome a mismatch in talent.

Geena Davis recently said that back in 1992, when the film came out, reporters would sheepishly ask if she thought it was a “feminist” movie. She always responded assertively that yes, as feminism was about equal rights and opportunities, then A League of Their Own was feminist.

I’m sure my mom would have agreed with her. Especially if the definition of feminism would include having the opportunity to knock your sister on her rear in a close play at home to win a World Series. What could be more fun – and egalitarian — than that?

Kelly Candaele produced the PBS documentary A League of Their Own about his mother’s years as a professional baseball player in the 1940s and wrote the story for the Columbia Pictures feature film.

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.