Coronavirus

Are Washington’s Farmworkers COVID-19 Guinea Pigs?

COVID-19 is spreading throughout central Washington state. One agricultural county has the highest infection rate on the West Coast.

Photos by David Bacon

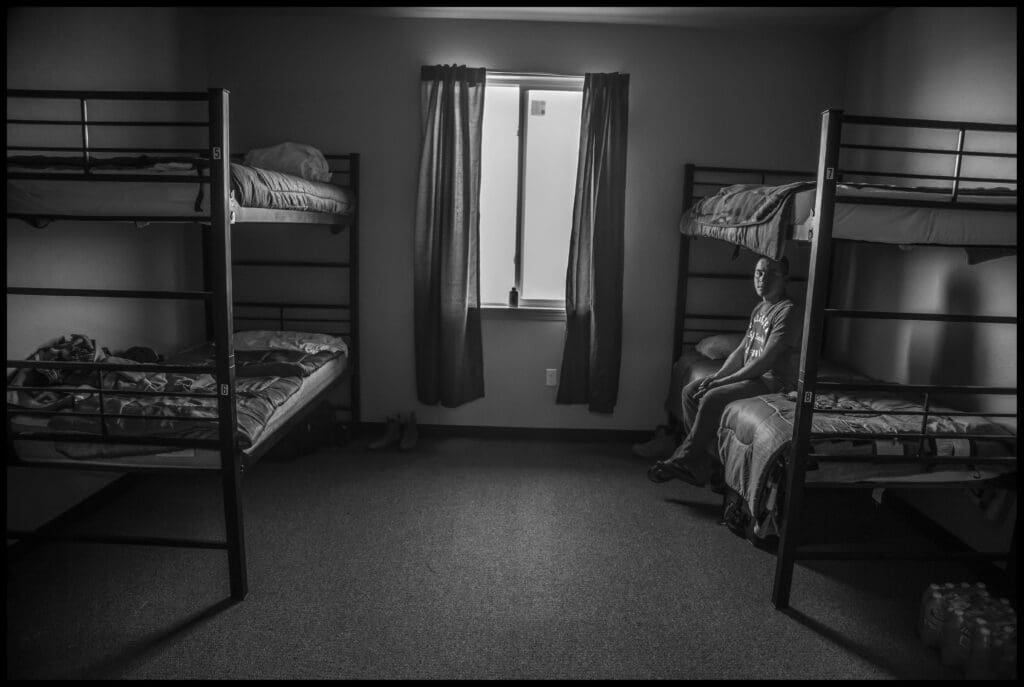

On March 12 an H-2A visa guest worker living in a Stemilt Growers barracks in Mattawa, Washington, began to cough. He called a hotline, was tested and found out he had COVID-19. He and five of his co-workers were then kept in the barracks for the next two weeks. A month later three Stemilt H-2A workers in a barracks in East Wenatchee began to cough too. Before their tests came back, three more started coughing. Soon they and their roommates were all in quarantine. Doctor D. Rutherford of the Confluence Health Clinic called Stemilt and suggested that all 63 workers be tested in the barracks. Thirty-eight tested positive. Then the virus spread to workers who’d tested negative.

The novel coronavirus continues to spread throughout central Washington state. By mid-May rural Yakima County had 1,203 cases —122 reported on May 15 alone — and 47 people had died. The county has the highest rate of COVID-19 cases on the West Coast — 455 cases per 100,000 residents.

Guest farmworkers are forced to sign a pledge

that authorizes their own blacklisting.

For over a week now, hundreds of workers in the same area have been walking out of apple packing sheds to demand better protections and more money for working in a situation where they may be exposed. “Workers are trying to call attention to the danger to the whole community,” says Rosalinda Guillen, a longtime farmworker organizer and director of the advocacy group Community to Community. Meanwhile, thousands more H-2A guest workers are scheduled to arrive in the area, first for the cherry harvest and then to pick apples.

Old barracks that were used in the 1950s to house guest workers in Blythe, Calif., in conditions similar to those of H-2A workers in Washington state.

H-2A workers (named for the visa program through which they enter the country) are recruited to work in the U.S. on temporary contracts; they can only work for the employer that recruits them, and they must leave once the work is done. For the last decade prefab barracks have been springing up in the middle of Washington’s blossoming apple trees, in orchards often miles from the nearest town.

The fate of thousands of these workers is at stake in a regulation handed down last week by Washington state’s departments of Health and of Labor and Industries that permits housing conditions that could cause the virus to spread rapidly. Sleeping in bunk beds in dormitories, according to these state authorities, is an acceptable risk. Yet according to Chelan-Douglas Health District Administrator Barry Kling, farmworkers are more vulnerable to getting COVID-19 because they live in these very close quarters. “The lives of these workers are being sacrificed for the profit of growers,” Guillen charges.

The barracks for Stemilt’s infected workers, like those housing thousands of others, are divided into rooms around a common living and kitchen area. Four workers live in each room, sleeping in two bunk beds. Stemilt says that it has 90 such dormitory units in central Washington state, with 1,677 beds. Half are bunk beds. Some barracks are ringed by a chain-link fence topped by barbed wire, while others have no barriers. If workers want to go into town to buy groceries or to a clinic, they depend on the grower to provide transportation.

* * *

Maintaining physical separation, especially in labor camps, “will be impossible under conditions H-2A workers typically experience in the United States,” concludes a report in April by the Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM — the Migrant Rights Center). There is no testing for H-2A workers as they enter the country, and until the infected group was found in Washington, there was no testing for them here either. Testing of the Stemilt workers showed they contracted COVID-19 once they arrived.

“They are treating us as disposable — as just cheap labor.”

According to Drs. Anjum Hajat and Catherine Karr, two leading epidemiologists at the University of Washington, “People living in congregate housing such as the typical farmworker housing … are at unique risk for the spread of COVID-19 because they are consistently in close contact with others … crowding increases the risk of transmission of influenza and similar illnesses. If individual rooms are impractical, the number of farmworkers per room should be reduced and beds should be separated by 6 feet. Bunk beds that cannot meet this standard should be disallowed.”

Washington’s state agencies decided to ignore Hajat’s and Karr’s testimony, however. In contrast, the same scientific analysis was the basis for a decision by Oregon’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration banning bunk beds. Its regulation issued in May tells employers: “Do not allow the use of double bunk beds by unrelated individuals,” and “beds and cots must be spaced at least six (6) feet apart between frames in all directions.”

Oregon authorities resisted pressure from employers to change the rule, but after a Farm Bureau survey of 323 growers claimed that it would result in losing housing for 5,000 farmworkers, its implementation was delayed until June 1.

Oregon, however, isn’t even among the top 10 states importing H-2A workers. California growers last year were certified to fill 23,321 farm labor jobs with H-2A recruits, yet no agency keeps track of the number of workers sleeping in bunk beds less than six feet apart.

Last year Washington employers estimated that 65,358 people were employed picking apples, making it by far the largest apple-producing state in the U.S. Its growers were certified for 26,226 H-2A workers. The vast majority worked in apples — as much as a third of the workforce. One company alone, Zirkle Fruit Company, was certified for 3,400 workers, while Stemilt was certified for 1,517.

Federal agencies have threatened to invoke the Defense Production Act to override any state actions that may cost growers money in order to protect their workers.

The state’s new rule for housing those workers says, “Both beds of bunk beds may be used,” for workers in a “group shelter,” consisting of 15 or fewer workers who live, work and travel to and from the fields together. Most Washington state growers would have little trouble meeting this requirement, since their barracks arrangement normally groups four bedrooms in the same pod. Stemilt also has vans that normally hold 14 people, conveniently almost the same number as in the bed requirement. A work crew of 14 to 15 workers would not be unusual.

By framing the bunk bed requirement in this way, Washington’s Department of Health effectively told growers that they did not have to cut the number of workers in each bedroom, and in each dormitory, in half. The rules of the H-2A program require growers to provide housing. If the number of workers safely housed in each dormitory were halved, growers would have two options. They could build or rent more housing, which would be an additional cost. Stemilt, with 850 bunk beds, would have to find additional housing for over 400 workers, and Zirkle perhaps even a thousand.

Dan Fazio, head of the Washington Farm Labor Association (WAFLA), one of the largest H-2A contractors in the U.S., called restrictions on beds to keep workers safely separated “catastrophic” and “a political stunt by unions and contingency-fee lawyers.” (Attempts to reach Fazio and other grower representatives for comments for this story were unsuccessful.)

Alternatively, growers could bring fewer H-2A workers to the U.S., and instead hire more workers either locally, or attract workers living in other parts of the country. This is what growers did until the H-2A program began to rapidly expand 10 years ago.

If the number of H-2A workers were cut in half because of the bunk bed requirement, however, Fazio and WAFLA would lose money, since their income is based on the number of workers they supply to growers. Last year WAFLA brought 12,000 H-2A workers to Washington, charging growers for each one (although it doesn’t disclose publicly how much).

WAFLA has made the H-2A program very attractive, helping to find contractors to build barracks, taking care of paperwork required for government certification and even pushing for lower wages. In the apple harvest most workers are paid a piece rate that used to reach the equivalent of $18 to $20 hourly. In 2018 WAFLA asked the state Employment Security Department (ESD) and the U.S. Department of Labor to eliminate any standard for piece rates, effectively slashing wages by up to $6 per hour. The ESD and DoL agreed. Fazio boasted, “This is a huge win and saved the apple industry millions.”

Many of the growers’ H-2A barracks were financed with Washington state funds that are allocated for building farmworker housing. Daniel Ford at Columbia Legal Aid, Washington’s legal service organization for farm workers, protested to the state Department of Commerce that growers shouldn’t be allowed to use public funds, since the state’s own surveys showed that 10 percent of farmworkers who are Washington residents were living outdoors in a car or in a tent, and 20 percent were living in garages, shacks, or “in places not intended to serve as bedrooms.” The department, however, refused to bar growers from using state subsidies to house H-2A workers.

* * *

Guest workers who complain are often blacklisted and denied jobs for the following season. One large recruiter, Consular Services Inc., a company closely associated with WAFLA, brings more than 20,000 workers to the U.S. every year. It has them sign a pledge that authorizes their own blacklisting: “I understand that if I don’t follow the rules at work, in housing or conduct, or my productivity on the job isn’t adequate, the boss has the right to fire me and I will lose all the benefit of my work visa, I will have to go back to Mexico, and the boss will report me to the authorities. This will obviously affect my ability to return legally to the United States in the future.”

The Centro de los Derechos del Migrante report casts doubt that the bunk bed regulation proposed by Washington state’s Department of Health, even with its weakened protection, can be adequately enforced. “The problem with protecting workers merely by promulgating regulations,” it emphasizes, “is that regulations cannot overcome the profound power imbalance between employer and worker under the H-2A program.”

In the spring of 2019 Community to Community, Familias Unidas por la Justicia and other farm worker advocates convinced the Washington state legislature to pass a bill to force state agencies to require protections for H-2A workers. The bill, SB 5438, “Concerning the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program,” was signed by Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee. It funded an oversight office and advisory committee to monitor labor, housing and health and safety requirements for farms using the H-2A program. It also required employers to advertise open jobs to local workers. Representatives from Familias Unidas por la Justicia, the United Farm Workers, legal and community advocates, and representatives from corporate agriculture were appointed to the committee.

* * *

When the coronavirus crisis began in early 2020, worker advocates asked the Department of Labor and Industries to issue regulations to guarantee the safety of the H-2A workers. Washington state, however, only issued “guidelines” that were not legally enforceable. Familias Unidas por la Justicia, Community to Community, the United Farm Workers, Columbia Legal Aid and the Northwest Justice Project then filed suit against the state, demanding enforceable regulations.

Skagit Superior Court Judge Dave Needy gave the state a deadline of May 14 to answer the suit, and the Department of Health finally issued the emergency regulation permitting bunk beds the day before the deadline. The unions sharply criticized the new regulation. Ramon Torres, from Familias Unidas por la Justicia, said, “We do not agree with this. They are treating us as disposable, as just cheap labor.” Erik Nicholson, national vice president of the United Farm Workers, said, “We are disappointed that the rules remain ambiguous and don’t provide the scope of protections that farmworkers living in these camps need to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus.”

“Those getting sick, and who may die, are poor brown people, and the families who will mourn them live in another country

two thousand miles away.”

The Washington court decision will have an enormous impact — not just on the state’s apple pickers, but on farmworkers nationally, because of the huge expansion of the H-2A program in recent years. Last year growers were certified to fill a quarter of a million farm labor jobs, and the Trump administration has sought to make the program as accessible and inexpensive for growers as possible.

Federal enforcement of protections for H-2A workers is almost nonexistent. The CDM report found that every worker it surveyed reported violations of labor rights and contracts. Nevertheless, of 11,472 employers using the H-2A program, last year the U.S. Department of Labor filed cases against only 431 (3.73 percent), and of them only 26 (0.25 percent) were temporarily barred from recruiting. “It’s deeply concerning,” Nicholson said, “that the federal government has been completely absent in ensuring that the essential women and men who harvest our food are protected.”

States have had to step in. California adopted regulations last year for H-2A housing, barring the use of public funds to build barracks. Washington state passed its law setting up a board to review standards and practices for H-2A recruitment. But the bunk bed ruling effectively makes Washington’s law toothless and leaves H-2A workers exposed to the virus.

In a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on May 19, however, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration warned that even regulations like the bunk bed ruling could be too much for the Trump administration. The agencies, they said, may invoke the Defense Production Act to override any state actions that cause “food resource facility closures or harvesting disruption [that] could threaten the continued functioning of the national food supply chain.”

Bruce Goldstein, president of Farmworker Justice, a farmworker advocate in Washington, D.C., called the MOU a “cold-blooded approach [to] the potential for widespread illness and death of farmworkers.” He added, “The Administration is claiming the right to prohibit states and local governments from requiring workplace safety precautions that might reduce the food supply while saving the lives of people needed in the food system.”

Protecting growers’ profits at the expense of the lives, health and wages of farmworkers has been the historical norm. But in the current COVID-19 crisis, calling farmworkers “essential” acknowledges not just that the country depends on their labor to eat. It also acknowledges that thousands of people go into the fields every day risking the virus. Farmworkers wonder if they then should be treated as vulnerable guinea pigs.

“The logic of declaring bunk beds acceptable is that some degree of infection and some deaths will happen, and that this is an acceptable risk that must be taken to protect the profits of these growers and this industry,” Rosalinda Guillen charges. “And what makes it acceptable? Those getting sick, and who may die, are poor brown people, and the families and communities who will mourn them live in another country two thousand miles away.”

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts