Labor & Economy

A Poorhouse Is Not a Home

Americans may be almost evenly divided about why a few people get so rich. But when it comes to why people are poor, there’s a general consensus: If people are poor, it’s their own damned fault!

This belief comes to us from British attitudes. Debtor prisons had a long tradition across the world, but England taught us that poverty was a moral failing. People were poor because they were sinful or impious or wastrels, so nothing could be done about it, and nothing should be done. Most Americans hold a similar view to this day, which is why the old “Welfare Queen” trope works so well for politicians.

Reality is less exotic. Real institutional systems make people poor and keep them there. Take wages. Despite California’s above-the-national-average minimum wage, no one can raise a family on it. Yet 65 percent of minimum-wage employees are the sole support of their family, on an income of only $16,640 a year. So people making that much – food service and child care and domestic workers, car wash guys, and gardeners (all the services middle class Americans depend on) — work more than one of those jobs to make ends meet. As one minimum-wage worker told me not long ago, “There are a lot of minimum wage jobs out there – I know – I have three of them.”

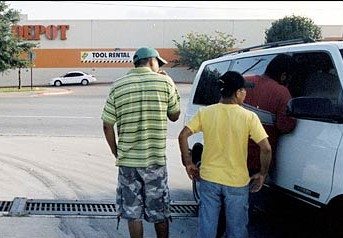

Often these people, poor and vulnerable, get cheated out of even that. When a car wash worker goes to cash a check at the end of the week, it often bounces. It has happened so often that workers can’t find a place that will take their paychecks. For day laborers this is part of the job – work all day, then get stiffed.

That’s only half it. These small-wage folks can’t cash their checks at a bank. Banks may be good for middle-income people, but they have too many rules for people with little money. Or often people come from countries where banks aren’t trusted. So these people turn to check cashing businesses, which charge a hefty fee for the service, usually a percentage of the check.

Check-cashing stores also offer instant lending. If a poor person has an emergency – say, hurt on the job or a sick child – a payday loan makes medical care possible. For a fee, of course, often at an annualized interest rate of 400 percent or more. The loan is repaid at the end of the week or with the next paycheck (which might bounce), but another loan is available. So even though it’s safer than the neighborhood loan shark, people get locked into a cycle of high-interest loans. Many of the largest funders of payday loans include America’s biggest banks — the very institutions that write rules that exclude the poor from their regular services. Some even own big chunks of the business, such as Union Bank of California, which owns a 40 percent stake in Nix Check Cashing.

Low-wage workers also need to get to their jobs, and in Los Angeles that often requires traveling some distance, often to a location with little or no bus service. So they need cars, but without savings and no credit, options are few. The most likely solution will be a “Buy Here/Pay Here” used car business. The dealer marks up the price, then makes a high interest loan, and will repossess the car if the buyer misses one payment. It is not uncommon for a poor person to pay ten times the car’s value, only to see it repossessed when they miss a payment late in the cycle.

These are three ways that institutions prey upon the poor with systems that keep people locked in poverty. The only way out of this wage-slavery is organizing into unions – the way janitors, security guards and home health-care workers have done. In Santa Monica and a couple of other sites in Southern California, they’ve been joined by the car wash workers. These workers didn’t take action to correct American social attitudes — just to stop being poor.

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 29, 2026Are California’s Billionaires Crying Wolf?

-

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 3, 2026Amid the Violent Minnesota Raids, ICE Arrests Over 100 Refugees, Ships Many to Texas

-

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026

Dirty MoneyJanuary 30, 2026Amid Climate Crisis, Insurers’ Increased Use of AI Raises Concern For Policyholders

-

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026

Featured VideoFebruary 4, 2026Protesters Turn to Economic Disruption to Fight ICE

-

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026

The SlickFebruary 2, 2026Colorado May Ask Big Oil to Leave Millions of Dollars in the Ground

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 5, 2026Lawsuits Push Back on Trump’s Attack on Child Care

-

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026

Column - California UncoveredFebruary 6, 2026What It’s Like On the Front Line as Health Care Cuts Start to Hit

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts