Immigration

A Photojournalist’s Lens on ‘More Than a Wall’

David Bacon spent three decades capturing the experiences of laborers, their treatment and where they came from.

If you have seen photography that brings to life the faces of farm laborers working the fields or on strike from Baja California to Yakima, Washington, it may well have been the work of David Bacon.

For 30 years, Bacon has documented the struggles of farmworkers and migrant communities through photographs, articles and oral histories, with a particular focus on California and the U.S.-Mexico border.

His path toward journalism passed through activism. As a young child in Oakland, he was questioned by the FBI about his blacklisted radical-leftist father. He was later drawn to Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement and got arrested for the first time when he was just 16, for taking part in a sit-in at Sproul Hall, which was then the main administrative building at the University of California at Berkeley.

During the 1970s, Bacon became a United Farm Workers organizer for about five years, a decision that profoundly affected the trajectory of his life. Later, he spent 20 years organizing factory and garment workers before becoming a photojournalist and writer to cover the world that he knew best — that of working people.

Bacon is now 74, and his award-winning work has been published widely — including in Capital & Main. He is the author of six books that chronicle labor, migration and the global economy. His most recent publication, in Spanish and English by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, is entitled More Than a Wall/Más que un muro, the fruit of his three decades covering communities and social movements on both sides of the border.

Bacon is now 74, and his award-winning work has been published widely — including in Capital & Main. He is the author of six books that chronicle labor, migration and the global economy. His most recent publication, in Spanish and English by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, is entitled More Than a Wall/Más que un muro, the fruit of his three decades covering communities and social movements on both sides of the border.

Over the phone from his longtime workshop in East Oakland, Bacon spoke about his journey from organizer to journalist, the common threads of those two professions and what we miss when our entire vision of the border is limited to a wall.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Capital & Main: Can you talk a bit about your background?

David Bacon: I was born in New York City. My dad was a local union president within the United Office and Professional Workers of America, which was the CIO’s union for white-collar workers. During the McCarthy era [in the early 1950s], the union was accused of being red and was thrown out of the [pre-AFL-] CIO and destroyed. After my dad was blacklisted, he found a job at the printing plant at the University of California. So when I was about 5, we moved to Oakland. In California, the FBI came around and tried to get him fired from his new job. One time when I was around 8, they even followed me home from school and tried to talk to me.

So, you grew up in a world of left-wing organizing?

I certainly knew what a picket line was and what a union was. My parents were radical. It was part of our culture. But it wasn’t like my mom and dad sat me down at the dinner table and told me everything that had happened. They didn’t talk about it a lot because they wanted us to be able to grow up without being afraid.

Tijuana, Baja California, 1996. Children of factory workers play in the street in front of their homes. Photos by David Bacon.

How did you get involved in the farmworker movement?

I started with the grape boycott, picketing Safeway and liquor stores. I began to wonder: Who are these people we are picketing for? I didn’t know. I was a city kid, an Oakland boy. The Black Panthers had a medical clinic a block away from my apartment, and I volunteered at the pharmacy. I was familiar with the big racial divide in Oakland, which was between Black and white. I didn’t know anything about Chicanos or Mexican people or immigration.

After picketing for a while, I joined the United Farm Workers in 1974. Eventually, I learned enough Spanish to be an organizer. My big teacher was Eliseo [Medina, a young farmworker who later became a UFW leader]. I had to learn about life in the fields, about the culture, about how the work was organized. Eliseo talked about building the revolution in the crew. You have to take a lettuce crew, say, in which the foreman is a dictator and the workers do what they’re told, and turn it on its head so that the workers become the ones who are powerful and the foreman is the one who has to watch himself.

What particular moments with the UFW stand out?

I remember talking to date workers, palmeros [farmworkers who harvest dates]. We had this very exciting meeting. This was the era before cherry pickers, when palmeros had to climb ladders that are nailed to trees and are rickety as hell. You fall 40 feet, and that’s it. They were fearless and proud and had already organized among themselves.

Oasis, California,1992. Workers climb ladders to harvest dates.

They said, “We don’t want anybody telling us what to do.” We said, “We’re not here to tell anyone what to do. You run your own ranch committee, and you enforce your own contract.” The next morning, I drove over to talk to the workers on the job. When I arrived, they were being loaded into a Border Patrol van. These proud workers were handcuffed and had their heads bowed down. I followed the van all the way to the detention center, and I remember standing outside the fence, not knowing what to do.

Another time, we had an election at a mushroom shed, and the morning of the election the [Immigration and Naturalization Service] threw up a roadblock on the way into the plant. You could see so clearly who benefited from immigration enforcement and who lost. That was a big lesson I’ve never forgotten. I’ve been an immigrant activist ever since.

How did you make the transition from being an organizer to a journalist?

After the farmworkers, I spent 20 years with different unions. I was usually the strike organizer, and I began taking pictures of our strikes. It was a good morale builder. We could pass photos out on the picket line and joke around, tell workers to show the photos to their grandkids 20 years from now. And I could give pictures to union newspapers and get some support. It was utilitarian.

In one of my last organizing jobs, we ran a strike at a big sweatshop in Pomona. We had 500 people from Mexico and Central America on strike, and you could feel with this strike and others, like the Justice for Janitors strikes, that there was an upsurge. The ground was shaking under our feet. By then, I was really into photography and decided I was going to document that strike from beginning to end. I carried my camera everywhere. At first, the workers thought it was a little strange [laughs].

Santa María Los Pinos, Baja California, 2015. The family of María Ortíz, a farm worker at Rancho Los Pinos. The workers in Los Pinos are almost all indigenous Mixtec and Triqui migrants from Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

What was your first journalism project?

I did a photo project in Coachella in the early 1990s about the palmeros. When I started taking pictures and writing, what was I going to take pictures and write about? The stuff I already knew. I had spent a lot of time working at the border — Calexico, Tijuana, San Luis Río Colorado — so I got to know border communities enough to be really interested in them. What does the border mean to people who have to cross it every day? To people deported and shoved back through the fence? To people organizing in the maquiladoras [foreign-owned factories usually located along the border]?

How is your job as a journalist different from your previous one as an organizer?

It’s a change in the way of going about things but not a change in the purpose or direction. The reason for doing this work is to help move the world forward. I write and take pictures of working people. That’s a conscious decision, a political decision. It’s a participatory kind of work — I’m a participant in what I’m documenting and not just parachuting in from outside.

When I started journalism, part of the reason was out of frustration. Although union organizing is very intense, you’re only reaching the people who are right there with you. We live in an enormous country in which 80 or 90 percent of people have no experience with unions, and I felt that we weren’t reaching enough people. Taking pictures and writing seemed to be a way of reaching larger numbers of people, with the idea being to change the way they think. Whether you’re doing it in a house meeting or doing it through photographs, the end purpose is the same.

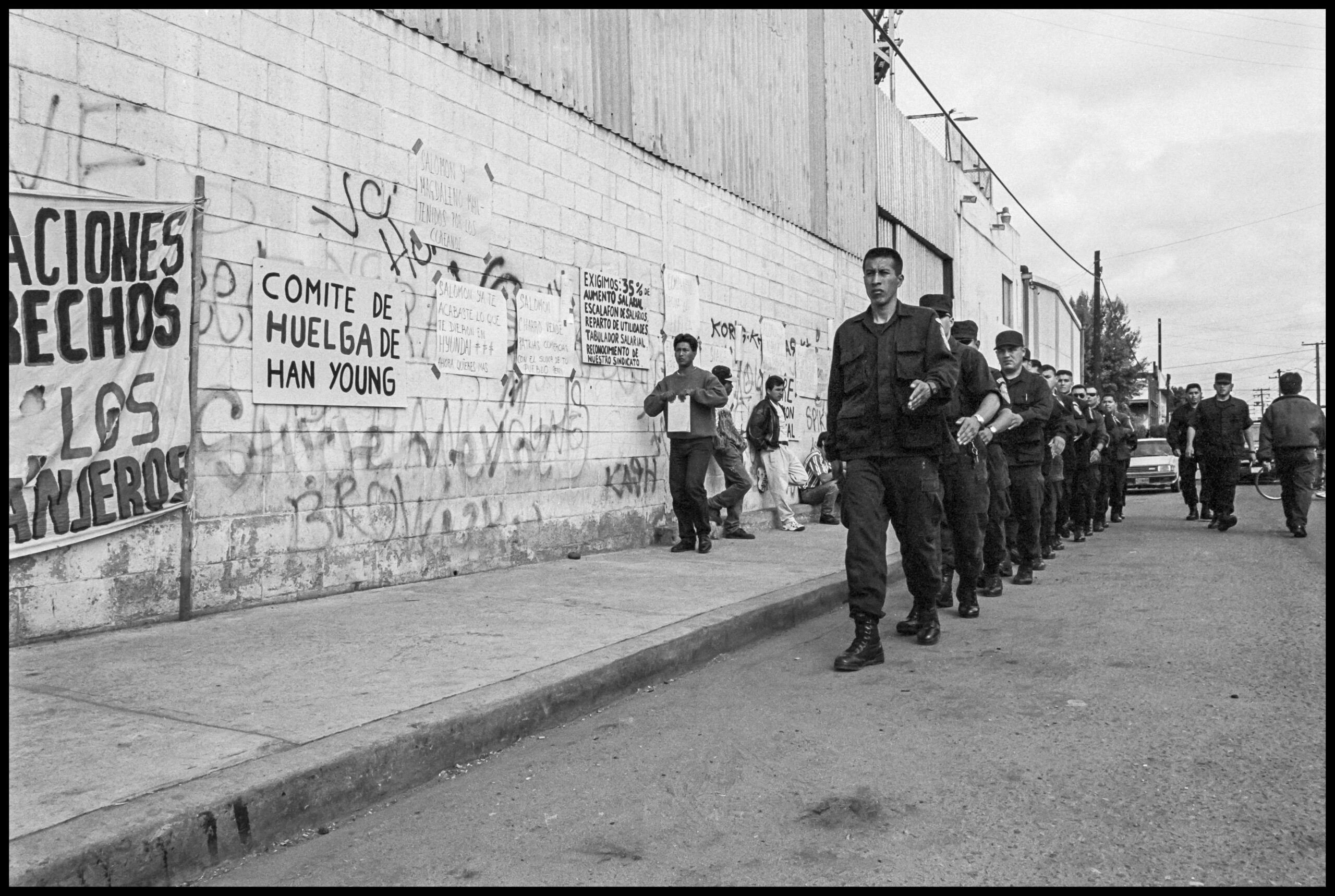

Tijuana, Baja California, 1998. Silvestre Rodríguez is a member of the executive committee of the independent union at the Korean-owned Han Young factory in Tijuana. Workers fought to organize an independent union at the plant.

One consistency in your journalism, dating back to the earliest days, is your exploration of the personal histories of workers to show how their previous experiences shaped where they are today.

One time, I met this older man who was part of an organizing drive of tangerine pickers. He had been involved in the land-reform fights in Baja California. They demanded the land of the hacienda [estate or plantation], and the hacendado [owner] had refused. So, they burned down the hacienda. Then the hacendado got his thugs to go after them, and this worker had to flee to the U.S. There he was, years later, working as a tangerine picker.

It made a big impression on me. I realized that people come to the U.S. with all of their political and social histories. When I record oral histories, I find out what happened to them in the places they are coming from, how they organized, their politics. I almost always end up asking: What is your idea of justice? What is a just world to you? Because it’s not just the concrete experiences they’ve had; it’s also the ideas that they bring with them. I have no patience for the kind of mainstream journalism in which [a reporter writes] about the concrete experiences of immigrants, and then they go off to some academic at a university and have it all interpreted. They ask the academic: “Tell us what it means.” I think that’s very demeaning to people. I’m interested in how people think, and what their ideas are and where their ideas come from.

Your new book is More Than a Wall. Why’d you choose that title?

The media is obsessed with the wall, which goes back to before Trump. This idea that all there is at the border is a wall, and all that happens is people try and cross it, with maybe some coverage of people dying in the desert. That’s certainly part of the reality. But I know, based on having been involved in different social movements for a long time, especially on the other side of the border, that the border is a region with a very long and rich history of communities. It includes people fighting for social justice, people just trying to survive.

So, I’m trying to get people to see that the border region is more than a wall. What counts is not so much the separation — although we have to deal with that and the consequences of it — but that we share a common history. We have to look beyond the wall to see the people, their communities and their history.

Tijuana, Baja California, 1998. Members of Tijuana’s special forces march beside the Han Young factory, as they prepare to illegally reopen the plant and bring in strikebreakers.

And yet the wall is also part of the border, and the first section of the book does focus on the wall.

It’s ironic because of course on the cover of the book is a photograph of the wall. There’s a man who has climbed up and is looking across to see where the Border Patrol is. Down below are his dog and a hole that has been dug. If nobody is around, he and his dog are going to crawl through the hole and make a run for it.

There’s a Nahuatl legend that says that if you die, you go into the underworld and are guided by a dog. So, here we have this man who is going to be accompanied by his dog as he crawls under the wall into this new world. And what is he looking at? Is he looking at a paradise where the streets are paved with gold? Is he looking at the place where immigrants are exploited and treated like shit?

One thing about the wall is that it can serve as an evocative backdrop for an artsy photo shoot, but then the symbolism tends to blot out the people living on both sides. And to understand the stories of the people takes an investment of time and resources. There’s no investment needed in just shooting a wall.

There’s this project that the artist J.R. made so people on the U.S. side would see the image of a baby leaning over the wall. Here the border is being used as a prop for this art piece that J.R. is doing because … well, I don’t know; maybe he had some good motivations about trying to encourage friendship. But what he did is he produced artwork that can only be appreciated from the U.S. side of the wall.

The U.S. media and U.S. cultural establishment is fascinated by the wall. I’m trying to say, “Fine, you find that the wall is interesting. That’s good because we need to recognize that it’s there, because it shouldn’t be there.” In the end, we should get rid of it. It’s offensive. But let’s not just look at the wall. What about the people there?

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main.

All photos courtesy David Bacon.

-

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026

The SlickFebruary 10, 2026New Mexico Again Debates Greenhouse Gas Reductions as Snow Melts

-

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 12, 2026Trump Administration ‘Wanted to Use Us as a Trophy,’ Says School Board Member Arrested Over Church Protest

-

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 10, 2026Louisiana Bets Big on ‘Blue Ammonia.’ Communities Along Cancer Alley Brace for the Cost.

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 12, 2026They’re Organizing to Stop the Next Assault on Immigrant Families

-

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026

The SlickFebruary 16, 2026Pennsylvania Spent Big on a ‘Petrochemical Renaissance.’ It Never Arrived.

-

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026

The SlickFebruary 17, 2026More Lost ‘Horizons’: How New Mexico’s Climate Plan Flamed Out Again

-

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026

Latest NewsFebruary 18, 2026Effort to Fast-Track Semiconductor Manufacturing Faces Community Pushback

-

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026

Column - State of InequalityFebruary 19, 2026Cuts Aimed at Abortion Are Hitting Basic Care