Coronavirus

Mariachi Plaza in the Age of Coronavirus

“I’m here fighting for my community,” said Eva García, who had come to a Food Not Rent protest in Boyle Heights.

There wasn’t much idle conversation going on in Mariachi Plaza de los Angeles on the morning of April 1. It was a beautiful day in Boyle Heights, but the square was nearly empty – gone were the commuters, vendors, and mariachi players in full regalia who normally populate the plaza. Near-constant honks from cars circling the square replaced the sounds of everyday life. Everyone was standing too far away from one another to talk without shouting.

The 40 or so people who were there were intent on their purpose. The bandannas and face masks they wore muffled their chants, but the meaning behind them – “We can’t work, we won’t pay!” and “Comida sí, renta no!” – was unmistakable. Passengers in the cars circling the plaza waved signs and shouted their support. Everyone knew what April 1 meant: The rent was due.

This is what a “social distancing” public action looks like in the age of coronavirus. The protest made it clear who in Los Angeles will be hardest hit by the financial impact of COVID-19: people of color living in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, under-the-table workers and undocumented people. It also underscored just how little those most affected by this crisis feel elected government officials are doing to protect them. For people who may not have a roof over their heads next month, staying home is an impossible choice.

“Being here is also a form of protecting my family”

The “Food Not Rent” action, organized by the L.A. Tenants Union, aimed to call attention to the difficult choices that many families in Los Angeles are being forced to make right now, and to demand a strong response from public officials. Eva García came despite being diabetic and worried about her family’s health and safety. She spoke rapidly, her words a little muted by a dark blue face mask. “I’ll go home and bathe [after this] to protect my family,” she told me, but “being here is also a form of protecting them. I’m here fighting for my community.”

The mariachis looked exhausted. A few were chatting.

Others simply stared at the ground.

García makes food for events. She lost her job six weeks ago, just before the pandemic hit California; now, it’s making it impossible for her to find new work. Her husband, a tailor, lost his job when his company was closed indefinitely two weeks ago. They’ve lived in Boyle Heights for decades, but even before this crisis, their rent had become nearly impossible for them to afford. “$1,500 a month — can you imagine?” she asked. (That’s $18,000 a year in a neighborhood whose median household income is less than $36,000 – and the Garcías are paying well below the median rent for Boyle Heights.) These days she spends her time online looking for both work and cheaper rental listings in the area but finds nothing.

García predicted that the crisis would lead to one of two diametrically opposed outcomes: Either the resulting upheaval could accelerate trends already squeezing working people – unaffordable rent, stagnant wages and rapid gentrification – or, just maybe, it could lead to something radically different. She gestured to the Reclaimers, a group of unhoused L.A. residents who are steadily taking over empty homes in El Sereno. Could it happen here?

“It would take real organizing,” García said, but then again, “Boyle Heights is a really organized community.” If the weeks and months stretch on without work, tenants in Boyle Heights may have no other option.

“It’s not the workers’ fault”

José Antonio wore a red bandanna that came up to just under his glasses and carried a black banner with the words “Choose food over rent” in both English and Spanish. He spoke quietly but precisely, asking the government to implement rent forgiveness.

“This is not the workers’ fault,” Antonio declared. He pointed out that people have many other expenses beside rent each month – food, medical expenses and other bills – and called on government officials and corporations to do more for people. “Corporations have resources – the working class doesn’t.”

Social distancing, Defend Boyle Heights claimed, would make public protest in this time of economic strife much more difficult.

“This is a national emergency,” Antonio said, “a global emergency.” He’s over 60 and worried about his health, but he came today anyway: “I don’t want to be here, but I’m taking precautions. I’m here in support of the people. ” Though he’s not personally worried about his finances, Antonio came out in solidarity with the many L.A. residents who have no idea how they’re going to make rent this month.

Antonio mentioned the unique hardship facing undocumented workers, the majority of whom pay taxes but will receive no stimulus check from the federal government during this crisis. Blanca, an organizer with the L.A. Tenants Union, likewise stressed the importance of rent forgiveness for tamale sellers and other street vendors who have completely lost their income. “We need to get the government’s attention,” she told me.

“The city council has sold out Boyle Heights”

Several members of the activist group Defend Boyle Heights were handing out a list of demands to the protesters: full work or wages regardless of immigration status, suspension of rent and utility bills and an end to “bans on protest and resistance.” Social distancing, they said, would make public protest, which is especially crucial in a time of such economic strife, much more difficult – even as many working class people classified as “essential” were risking their safety to do their jobs.

On Tuesday evening, Defend Boyle Heights had shown up at the home of Los Angeles City Council member José Huizar, demanding that he do more to fight for the needs of his District 14 constituents.

“There’s absolutely no work for mariachis right now,”

Arturo Ramírez said. “Nothing, nothing.”

“He didn’t come out,” said one of the members, a chef who has been temporarily laid off due to the coronavirus. “I think he was embarrassed.” Huizar and the rest of the city council, he said, have “sold out” Boyle Heights. Last week, the council stopped short of protecting all tenants from evictions during the crisis (the measure they passed would halt evictions only for those who can prove they have been impacted by coronavirus); they haven’t taken up stronger tenant-protection measures such as a rent freeze, which would prevent landlords from raising rent during the pandemic, and full rent forgiveness (Huizar and City Council President Nury Martinez did not return repeated requests for comment for this article).

“There’s absolutely no work for mariachis”

There actually were mariachis present in the plaza last week, but I didn’t recognize them immediately. Absent their uniforms and instruments, the 10 or 12 men, most wearing red T-shirts, sat in the shade under one of the plaza’s few trees.

The mariachis looked exhausted. A few were chatting; others simply stared at the ground. Their leader, Arturo Ramírez, seemed uninterested in talking at first. But when he finally looked up from his phone, he spoke passionately. “We’ve been sending letters to [Los Angeles Mayor Eric] Garcetti” to ask for economic relief, he said. “It’s three weeks without work now. If the authorities don’t intervene, it’s going to be a really serious situation.”

The mariachis are a fixture at the plaza. People hire them for weddings, quinceañeras, or a backyard asada by contacting them on social media or just driving by and asking them to play. Now, Ramírez says, “everything’s canceled” – and with it, their entire livelihood. The men are in contact with mariachis across Southern California and Mexico, but everyone’s in the same boat. “There’s absolutely no work for mariachis right now,” Ramírez said. “Nothing, nothing.”

Ramírez doubted that the mariachis would receive any governmental assistance because of the irregular nature of their work. “There’s no way to collect it,” he said. “The government considers us workers who don’t have regular work.” (Under the CARES Act signed into law March 27, independent contractors should have access to unemployment insurance—but none of these men had heard anything about it).

What were they going to do? “We have to stay here,” Ramírez said, on the off chance that someone will come to the plaza and ask them to play. “We’re not loitering, just looking for work.” He sighed and looked around at his bandmates. “We’ll be here.”

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

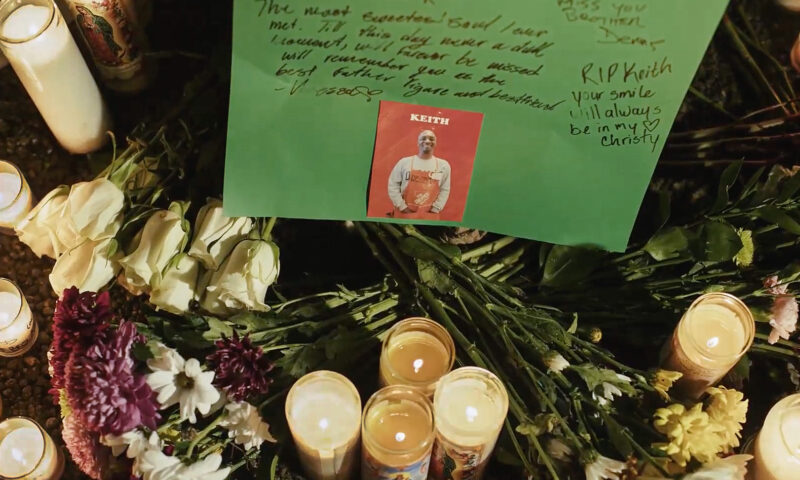

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026Can California’s New Immigrant Laws Help — and Hold Up in Court?

-

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026

Column - California UncoveredJanuary 14, 2026Keeping People With Their Pets Can Help L.A.’s Housing Crisis — and Mental Health

-

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 16, 2026Homes That Survived the 2025 L.A. Fires Are Still Contaminated

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026

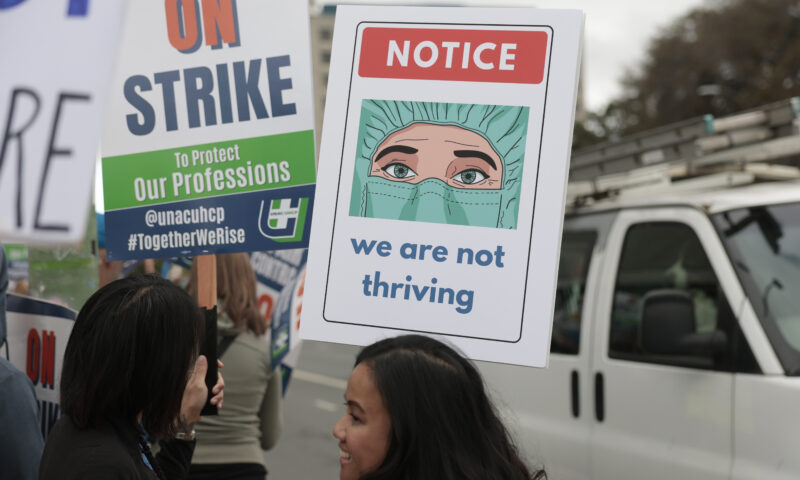

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 22, 2026On Eve of Strike, Kaiser Nurses Sound Alarm on Patient Care

-

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026

The SlickJanuary 20, 2026The Rio Grande Was Once an Inviting River. It’s Now a Militarized Border.