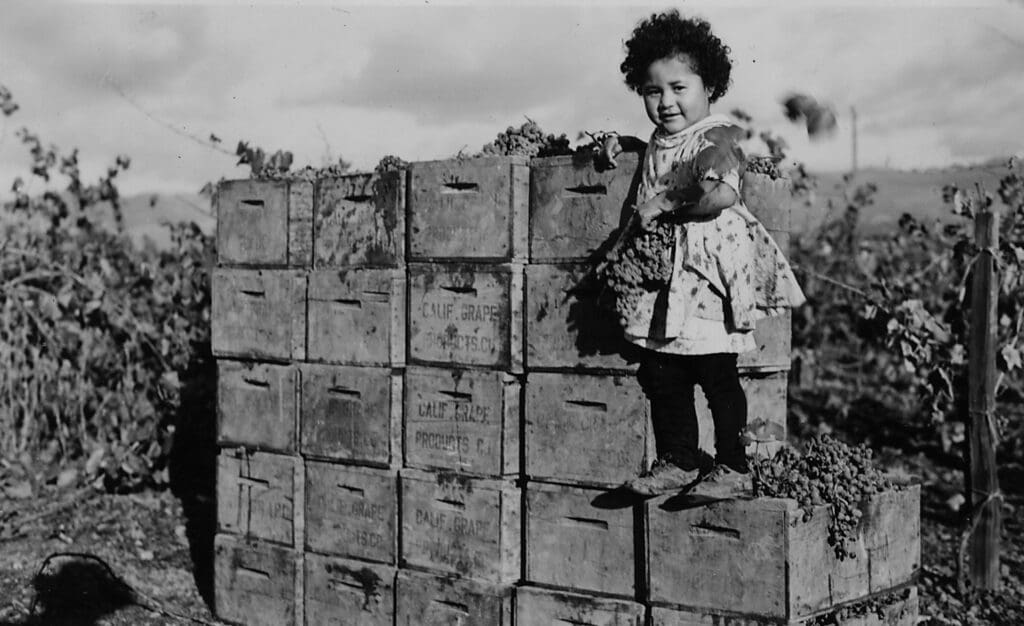

Rural Poverty in California

Down and Out on California’s Reservations

For Indians who are not part of a casino-connected tribe, life on the state’s reservations and rancherias can be a hardscrabble existence.

“The location of Fort Bidwell is pretty landlocked,” says Kevin Dean Townsend, chair of the Gidutikad Band of Northern Paiute, also known as the Fort Bidwell Indian Community, in Modoc County, in remote northeastern California. Roughly 40 tribal members, he estimates, still live on the 3,300 acre reservation, on rugged, mountainous land not too far from the Lassen volcano, to which the tribe, part of the Northern Paiute, was forcibly relocated in the late 19th century. Ironically, a generation earlier the Fort had been built to protect Anglo settlers from people the state referred to as “marauding Indians.”

Since Fort Bidwell doesn’t run a casino, its members qualify for a small quarterly payment from the pool that the state’s gaming tribes set aside to distribute to the others. A good quarter, Townsend, says, might result in a $700 payment to each member over the age of 18. Other than that meager income, Fort Bidwell Indian Community members find seasonal farm work, hunt for meat, scrape together odd jobs and utilize government benefits.

Housing is distributed by the tribal government, water is free (though occupants have to pay utility bills), and residents pay no property taxes. The low cost of housing is a powerful lure keeping tribal members on the reservations and rancherias throughout California. Yet it’s still a hardscrabble existence.

“One road comes in and it’s not maintained very well. Our nearest gas station is 26 miles away, and it’s nearly $5 a gallon,” explains Townsend. “There’s a little grocery there; it’s pretty expensive. The nearest grocery store that’s a little bigger is 56 miles away in Alturas. It’s hard to get there in winter.” Getting kids to school involves a 90-minute bus trip each way to the little town of Cedarville.

The Fort Bidwell Indian Community is one of roughly 100 Native American communities dotted around California, living either on ancestral lands; on remote reservations to which they were forcibly relocated after the discovery of gold in 1849, when settlers launched a genocidal land-grab against the indigenous populations; or on rancherias purchased for landless Native communities in the early 20th century.

Tribal stories tell of an era of forced marches, such as the Nome Cult Walk in 1856, when tribes were driven out of the Chico area and up into the Covelo Valley; or the Bloody Run of 1871, when the Pomo tribe was rousted from Potter Valley by militias, and the local Eel River supposedly ran red with the blood of the dead. The federal government and the young state of California grotesquely spent the modern equivalent of millions of dollars paying out per-head bounties to those who murdered Native Americans. And, for their descendants, there are stories of exile from traditional lands with their reliable food and water sources, and relocation onto inhospitable, often infertile terrain.

“You take all these people who live in these separate locations, put them together and ask them to figure it out,” says William Feather, whose great-grandfather was one of the few Maidu tribal members to survive the Nome march, and who himself grew up on reservation land in the deeply impoverished Round Valley, high up among the inland mountains of Mendocino County. “The result is really self-extermination. There’s a lot of violence. How much grief and loss was experienced on the reservation. A lot of preventable deaths: DUIs, diabetes, alcoholism, suicide, accidental overdose.”

Centers for Disease Control data backs this up: The CDC reports that Native American communities have the highest per capita motor vehicle fatality rate caused by alcohol of any racial group in the country. Since 1999, the suicide rate for Native Americans, which includes Native American youth, has increased a staggering 139 percent for women, and 71 percent for men – a far higher increase than for the non-Native population. And when it comes to opioid overdose deaths, Native Americans have the second-highest rate of any racial group in the country.

* * *

In the late 1950s and 1960s, as part of the U.S. Congress-mandated policy of “terminating” a number of tribes and distributing their lands to individual tribe members, more than four dozen of California’s tribes were terminated. The ostensible goal was to force integration on the Native population. But in reality, when the government ceased to recognize their tribal structures and leadership, it served mainly to break down political and cultural cohesion, leaving the populations even more economically and politically vulnerable.

As a result of lawsuits, in recent decades tribes have managed to reclaim their status and some of their land. But the legacy of termination added yet another layer of damage to a history riddled by violence and exploitation.

“We know we have communities that are sick,” says Dino Franklin, tribal chair of the small Kashia tribe, which was forcibly relocated away from the coast in the decades after the Gold Rush and dumped onto 46 acres of land, named Stewart’s Point, in the hills of Sonoma County. That land was formally consolidated into a rancheria in 1914. The dislocation, he believes, plays out across generations. Today, there are sky-high levels of meth and opioid addiction. “We have a lot of historic trauma on our res,” he explains. “We’re a very impoverished people.” There are no businesses at Stewart’s Point and only a few jobs available in tribal government.

Mark LeBeau, of the Roseville-based California Rural Indian Health Board, quotes data indicating that nearly 13 percent of the Native population in California has diabetes, compared to a statewide average of six percent among non-Hispanic whites. Another 11 percent is pre-diabetic. LeBeau, a tall man with a long ponytail and a graying goatee, is a member of the Pit River Nation and grew up extremely poor in multiple places in the northern part of the state. Now working in public health, he worries about the number of tribal communities that are food deserts, which can lead to a host of health problems, including diabetes, obesity and heart disease. Of Fort Bidwell, for example, he says, “They’re isolated. There’s one road in, one road out, and they’re at the end of the road. To the north are mountain ranges; to the east is Nevada, high desert and plains. The nearest town with food markets is Alturas, an hour’s drive away. Food prices are higher; and produce is a bit weathered by the time it’s trucked all the way up there.”

* * *

Poverty has long been rendered invisible in American policy discussions – more than a half century ago, Michael Harrington vividly described how it didn’t fit the postwar narrative of endless upward mobility. And poverty among Native Americans tends to be even more ignored by those seeking to shape the policy discourse. Yet, in truth, no discussion of economic dislocation in America can be complete without a reckoning of the ingrained, multigenerational poverty found in Native American communities. Indeed, across the country, some tribes experience unemployment rates above 40 percent. Those with rates above 50 percent are exempted from the general time limits on welfare usage codified in the 1990s.

In California’s larger tribal communities, such as the Karuk in Humboldt and Siskiyou counties, and the Yurok in neighboring Del Norte – which have managed to remain on their ancestral lands, and have tried, with varying degrees of success, to economically diversify in recent years – residents suffer extremely high drug addiction rates, epidemics of diabetes and suicide, and pervasive poverty. Among the Karuk, 39 of the 194 households living on the reservation in remote, densely wooded lands just south of the Oregon border have an annual income of less than $10,000, according to American Community Survey data from 2017.

For the Yurok, that number is nearly one in five. The federal poverty line is roughly $25,000 for a family of four. Within small tribal communities, poverty is even more pervasive: Fort Bidwell’s membership includes 47 households; 15 are estimated to have household incomes under $10,000. And even when income levels don’t fall quite as low as this, families living on tribal lands still routinely struggle to make ends meet. On many rancherias, more than 30 percent of residents live below the federal poverty line.

In Mendocino County, upwards of a dozen small tribes live, some on the edges of small towns, some along the coast, others far off the highways in the high-plateau Covelo Valley. A number of Mendocino’s tribes, such as the Coyote Valley, have in recent years opened casinos and purchased smart new modular homes for members with the proceeds, the bungalows ranging neatly down rancheria streets that look like generic suburban tracts. But others, such as the Cahto tribe’s rancheria and the villages of the Round Valley, remain desperately dilapidated, the untended roads pot-holed, with untethered pitbulls roaming them. The buildings, most of them trailers, are ramshackle, with large tarps over yards that hide illicit marijuana grows – much of the local economy is reliant on Northern California’s decades-old pot industry, and has suffered profit losses in the legalized-pot era.

While many regions of the state that previously relied on illegal revenues from the pot trade have managed to go legit following the state’s vote to legalize marijuana, so far the tribes have been unable to do so. To access the market, they would have to either cede regulatory power – and thus a degree of sovereignty – to the state’s Bureau of Cannabis Control and its Department of Food and Agriculture, or sign a compact with the state, much like ones that allow gambling on tribal lands. So far the tribes haven’t shown an interest in ceding regulatory power, and the state hasn’t made any moves to forge marijuana compacts with the tribes. As a result, tribes have been frozen out of the legal marijuana market, their growers operating in a black market.

The resulting poverty in turn creates additional challenges. The 2010 census found that six percent of the county’s population was Native. But, Dr. Libby Guthrie of the Mendocino County AIDS/Viral Hepatitis Network (MCAVHN), sitting in her small office in downtown Ukiah, its walls covered with Rolling Stones posters, says that fully a quarter of public health services are used by the indigenous population, an indicator of the scale of economic need.

Not surprisingly given the history, Guthrie says, the tribes are deeply suspicious of outsiders. “Unless we are able to go into communities, they don’t reach out to us and ask for help. There’s an attitude, ‘Screw you; you’ve done nothing but shit on us.’” But this isolation further removes them from economic opportunities and preventative public health measures. As a result, what could be containable problems become crises: epidemic levels of obesity lead to full-blown diabetes; alcoholism to cirrhosis; intravenous drug use to high levels of hepatitis C; and so on.

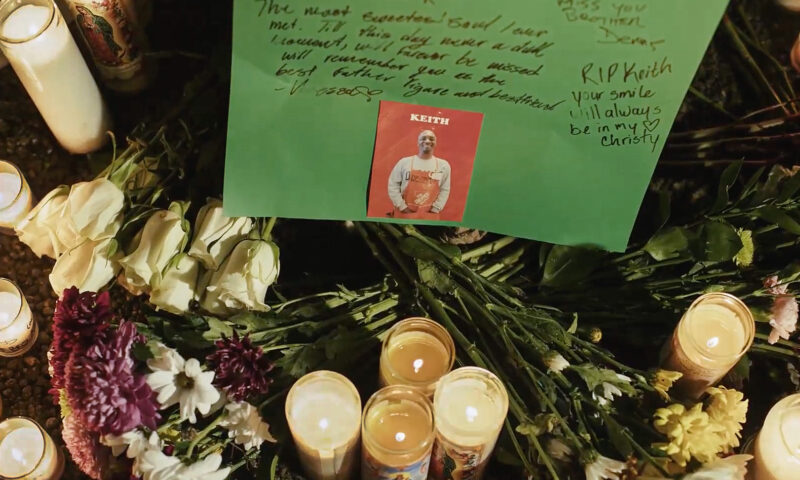

Outsiders simply aren’t trusted, says Keith Driver, an outreach coordinator with MCAVHN who spends his days in his Chevy Volt crisscrossing the forested county, delivering clean needles to addicts, working with the homeless, and helping Hepatitis C, HIV and AIDS patients access services. “Covelo [Valley] is always a battle,” he explains. At times, he and his co-workers have been run off of rancheria lands by suspicious locals. But, he says, since there’s a job to be done they always return; not alone, however, and never after dark.

“A lot of the economics, the health issues, stem from historical trauma,” says Pinoleville Pomo tribal chair Leona Williams, as she sits at a long conference table in her modular unit office on the outskirts of Ukiah. Williams, aged 70, recalls family stories of an ancestor being forced off his land and becoming indentured to an Anglo landowner, of the rest of the family being force-marched to the Round Valley, of women being raped, children being killed. She talks about children well into the 20th century who were sent to schools where they were fiercely punished if they didn’t speak English. She herself recalls attending lessons in the local school in which her people were described as “savages.” This, she recalls, “was humiliating. I’d sink down in my seat.”

Williams’ deputy, Angela James, a generation younger than her, concurs. “No matter where you go, you carry that with you. I did go through an anger stage in my life.” The trauma, says James, leads to substance abuse and domestic violence, amongst other problems.

Inside the Mendocino County Jail, on an average day at least 10 percent of inmates are Native American, and some days that number spikes far higher. William Feather, who currently works inside the jail as an inmate services coordinator, talks of “the lack of opportunities, resources, and employment” on the reservations. He also worries that once people return to the community from jail or prison, probation and parole services don’t have the resources to work effectively. There is, he argues, a “lack of county, state and federally funded programs.”

Feather leans forward as he talks, a large man wearing black cargo pants and black top, a beaded necklace, his long hair tied in a ponytail, eyeglasses perched down his nose. He says that he sees “a lot of mental health issues, PTSD, depression. You can probably pick any diagnosis out of the DSM, and if a therapist sat long enough with any tribal member, you can find some of that.”

* * *

The challenges around poverty in these communities are enormous. But they aren’t necessarily insurmountable.

Many are starting to take part in the White Bison program, first developed 20 years ago by tribal communities in Colorado, which uses Department of Education grants to promote sobriety, addiction recovery and health, as well as to train tribal members for local jobs. The program taps into traditional healing and spiritual systems to engage participants more fully.

In Pinoleville, a Head Start program now offers services, including the weekly distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables, to 60 families. “Usually that’s where their meals come from,” says Angela James of the children in the program. Head Start also links the children up with dental checkups, hearing exams and eye tests. Pinoleville is also working with state officials to set up the first tribally owned opioid clinic in the state – modeled after one in Washington state.

For Feather, these developments are positive, but not enough. He believes that the state of California should pay reparations to the tribes for all the damage done over the past 170 years, and that it should come in the form of investments in local jobs and economic infrastructure. “You hire the people who live there. In all tribal communities there’s somebody who’s respected. But we as a society discard them because they don’t have the credentials. Every dollar the state spent on murdering us, I’d like them to match in current day figures to help combat these issues. The state really does need to step up their game and really help.”

Copyright Capital & Main

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025From Fire to ICE: The Year in Video

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 8, 2026Can California’s New Immigrant Laws Help — and Hold Up in Court?