Culture & Media

Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Oasis

For those who missed the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada exhibit, you can still experience his extraordinary art born of the Watts riots at the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum, in the town of Joshua Tree.

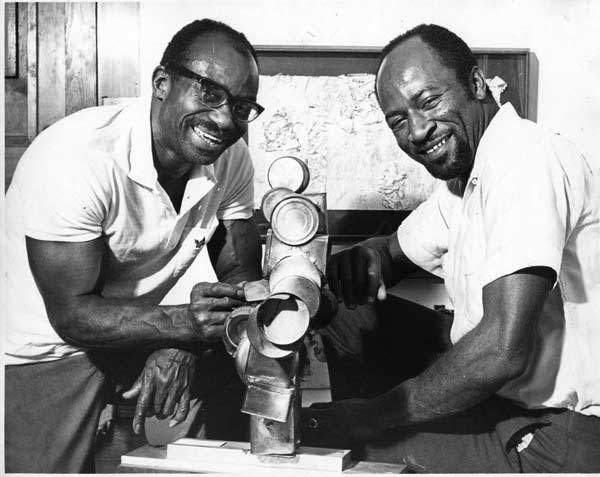

Noah Purifoy, left, with Judson Powell.

For those who missed the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada exhibit, you can still experience his extraordinary art born of the Watts riots – in fact you can see a lot more of it – at the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum, in the town of Joshua Tree, just north of the national park. A truly extraordinary menagerie of the living potential – and art – of what we call garbage, it’s nothing short of a small city perched on the edge of time. It’s also a record of what our civilization has created for its own utility — a lesson that, in the hands of an artist, is revealed as somehow alive and beautiful, not so much for its purpose, but rather for itself, for its form, color and shape.

One untitled, rollercoaster-like sculpture caterpillars over the Mojave sand (see above), made of oven trays. Another assemblage, composed of colorful stacks of cafeteria trays, spiral upward to an enclosed space’s ceiling, and resembles a classroom model of a DNA ladder — suggesting that Purifoy is commenting on how consumer culture endlessly serves up tray after tray of, well, everything.

You’ll find a lot of toilets at the museum as well, including one reminiscent of Dadaist granddaddy Marcel Duchamp’s infamous urinal sculpture, Fountain. In fact, Purifoy’s White/Colored (see below) is an almost direct reference to that work.

Like recombined DNA, Purifoy’s work is the world re-interpreted through its waste, or to make a biblical reference: “The stone rejected by the builders has become the cornerstone” of Purifoy’s vision. This is a thinking person’s museum, but you’ll do more than just think. There is plenty of whimsy here as well, like Carousel, a structure whose interior was full of desks and computer equipment, bringing a smile and a sigh to this office worker.

Such is Dada, which since its beginnings following World War I, has always been essentially intellectual, anti-bourgeois and anti-war, mixing up imagery and pointing out the absurdity and even violence of consumer culture, much of which depends on the global trade that makes it possible.

Purifoy was born in Alabama in 1917, around the same time as the Dadaist movement. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he found himself in Los Angeles, where he became the first African-American to enroll as a full-time student at the Chouinard Art Institute, which would later become CalArts. At first he worked in interior decorating and furniture design, but the 1960s – particularly the Watts riots – affected him as it did so many others, causing him to begin questioning consumer culture, among other things, before abandoning his design career to focus wholly on his art. In the process, he became a leading proponent of what was, at the time, arguably a rebirth of Dada.

After the Watts riots of the summer of 1965, Purifoy, along with fellow local artist Judson Powell, organized an art exhibition made up of 50 works created from materials salvaged from the destruction as a way to “interpret the August event.” Six artists displayed their work, which ultimately traveled to nearly a dozen California universities and to venues across the country. For the next 20 years, Purifoy dedicated himself to such salvaged art, collecting discarded materials and creating work with the goal of promoting social change. Purifoy was a cofounder of the Watts Towers Art Center, and served on the California Arts Council, creating Artists in Social Institutions, which encouraged artists to work, show and teach in the state prison system.

Ultimately, Purifoy moved to the desert, like dozens of artists before him, and lived for his last 15 years (he passed away in 2004) on this parched patch of land in a trailer at what is now his open-air museum. But lest you think Purifoy had withdrawn and wholly removed himself from what was going on back in Los Angeles, there’s Ode to Frank Gehry. For though one is struck by the man’s singular vision and the isolation in which he worked, it’s clear that everything he did remained pertinent to the society he emerged from and that continues to churn out the endless array of “stuff” that will feed infinite amounts of work like his in proceeding years, speaking through what is discarded, as if whispering Blake’s words in your ear as you stand in the empty, breezeless desert:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

Except where noted, all photos courtesy Noah Purifoy Foundation © 2016.

-

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026

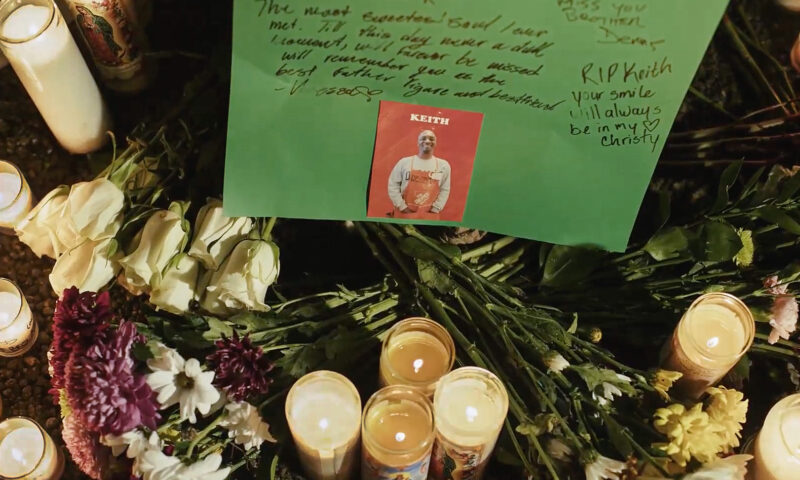

Latest NewsJanuary 8, 2026Why No Charges? Friends, Family of Man Killed by Off-Duty ICE Officer Ask After New Year’s Eve Shooting.

-

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 29, 2025Editor’s Picks: Capital & Main’s Standout Stories of 2025

-

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025

Latest NewsDecember 30, 2025From Fire to ICE: The Year in Video

-

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026

Column - State of InequalityJanuary 1, 2026Still the Golden State?

-

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026

The SlickJanuary 12, 2026Will an Old Pennsylvania Coal Town Get a Reboot From AI?

-

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 6, 2026In a Time of Extreme Peril, Burmese Journalists Tell Stories From the Shadows

-

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026

Pain & ProfitJanuary 7, 2026Trump’s Biggest Inaugural Donor Benefits from Policy Changes That Raise Worker Safety Concerns

-

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026

Latest NewsJanuary 13, 2026Straight Out of Project 2025: Trump’s Immigration Plan Was Clear