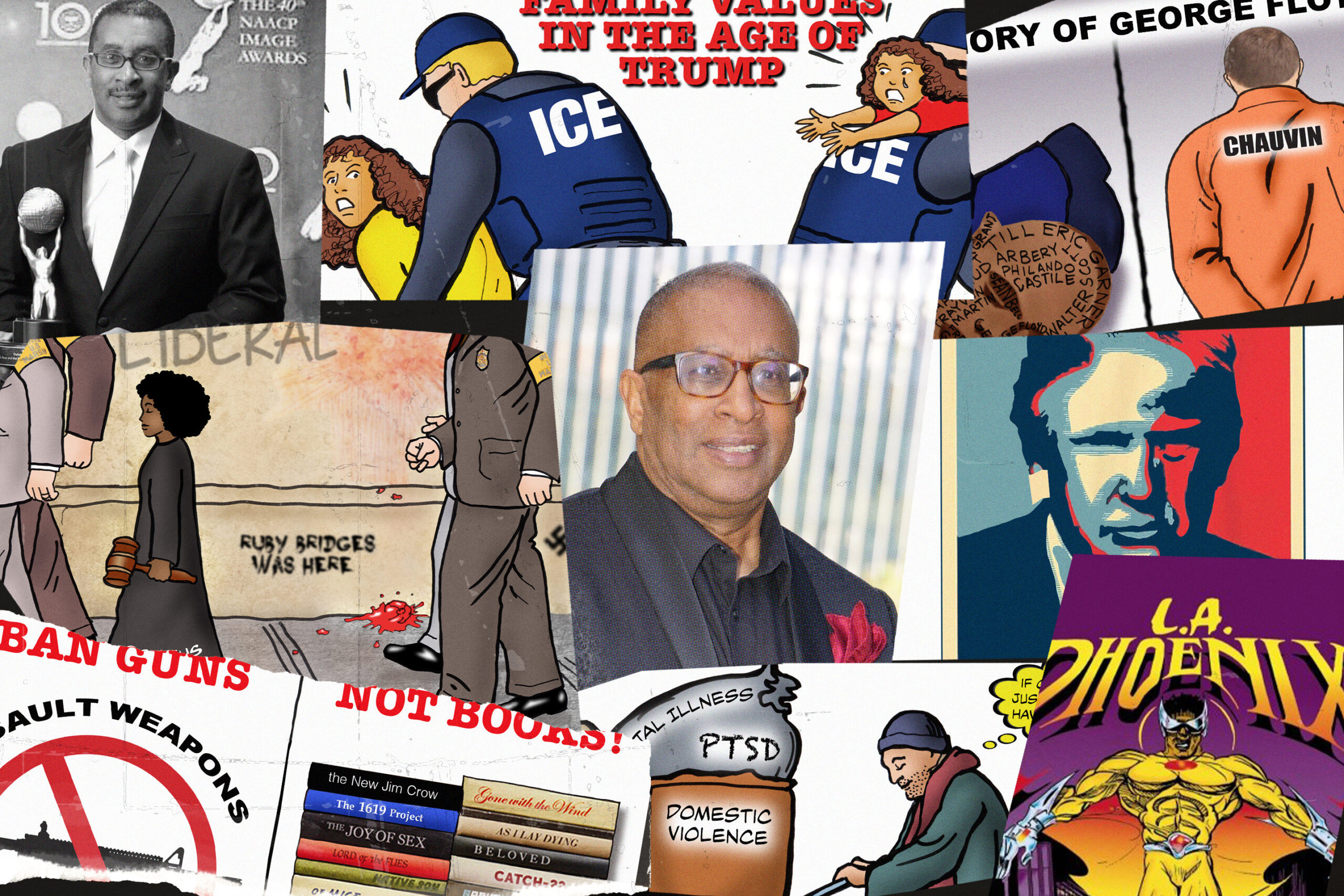

David G. Brown, political cartoonist for the Los Angeles Sentinel, the city’s oldest Black newspaper,

reflects on the art of racial dissent. An exhibit at the Watts Towers showcases his work.

By Erin Aubry Kaplan

How does a Black artist satirize a racial reality that has gone way beyond satire under President Donald Trump? It’s something David G. Brown asks himself every week.

The longtime political cartoonist for the Los Angeles Sentinel, the city’s oldest Black newspaper, says coming up with effective responses to the almost daily outrages emanating from the White House is a challenge that often leaves him at a loss for words, and for images.

But Brown is nothing if not persistent. After more than 20 years capturing the racial zeitgeist in his weekly cartoons, from the high point of Barack Obama’s election as the first Black president in 2008 to the nadir of Trump and his reelection, one thing Brown has learned is that the fight for justice will always face obstacles that need to be exposed.

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

David G. Brown.

“It’s frustrating and disappointing, where we are now, but Black people can’t give up, or shut up,” said Brown, who’s 71 but, despite his gray hair and glasses, looks much younger, with the wide-eyed energy of a high schooler to match. “I’ve become bolder. It’s not the time to be meek.”

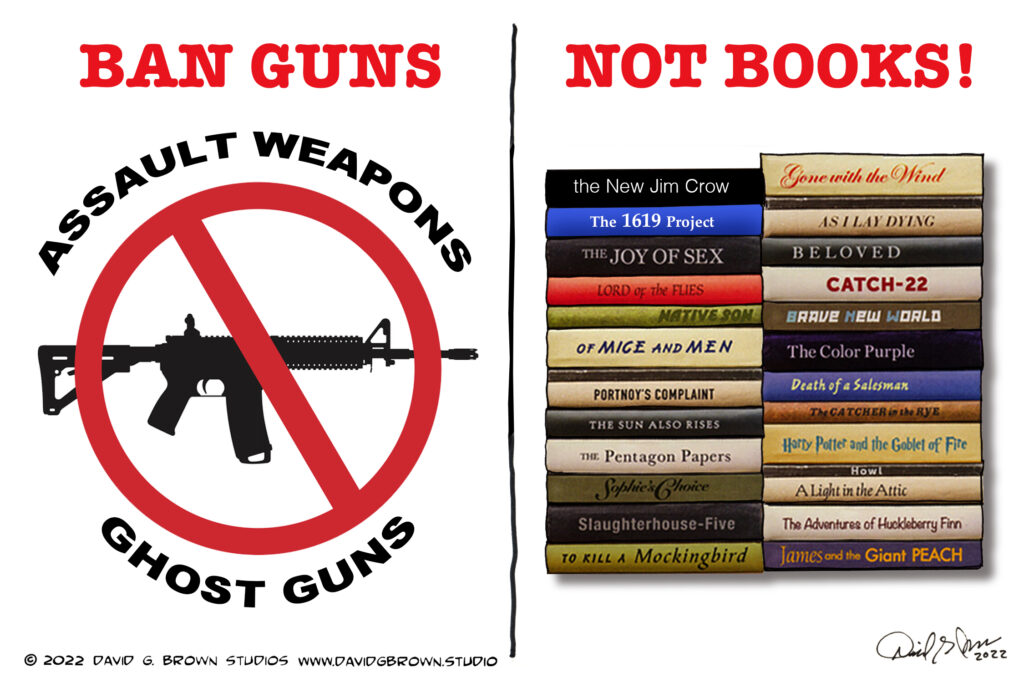

Indeed it isn’t. Among Brown’s recent Sentinel cartoons is one depicting a group of survivors of Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking admonishing Trump to be “Quiet, Piggy” (a reference to the president’s insulting admonishment to a female reporter’s questions) as he descends a not-so-golden escalator of declining poll numbers. Another recasts the traditional presidential seal with the bald eagle wearing a red MAGA hat, clutching a bag of cash in one claw, with the word “president” replaced with “felon.”

As he continues to tackle the transgressions of Trump and MAGA, Brown is also pausing to look back. A retrospective of his Sentinel cartoons, “Politics, Race and the Media: Two Decades of Drawing My Own Conclusions,” is on exhibit at the Watts Towers Arts Center Campus, along with works by the pioneering Black political cartoonist Ollie Harrington. The exhibit, which runs through Feb. 21, highlights work in Brown’s recently published book of the same name.

Brown’s cartoons are pointed but genteel, reflecting both his seriousness and a fundamental optimism. Whether they’re exalting Black History Month or exploring the hypocrisies of Trump or other figures, like former GOP stalwart Condoleezza Rice, they tend to be rendered in primary colors, and are accessible to most readers.

Watts Towers Arts Center Campus director Rosie Lee Hooks, who curated the exhibition, wrote that Brown’s “quality of stilled laughter is mild and divisive at the same time, displaying the corrupt ways of racism and injustice throughout the world.”

That enduring quality was well suited to the moment that Brown got started more than two decades ago. Back then, he was deeply critical of George W. Bush (“I thought he was the worst president ever,” Brown quipped recently) and the neoconservative movement in the country following 9/11. But then came the Great Recession that began in 2007. The downturn hit Black people especially hard, and provided an on-ramp for the election of Obama. It was a pinnacle of Black achievement, and Brown was happy to celebrate it in his many depictions of President Obama as evidence of both racial and national progress (one of his cartoons from 2008 presents Obama as an unabashed Superman). But in his cartoons he also cautioned that the election of the first Black president was not the end of history.

Still, Brown said, “I had no idea what was coming.”

* * *

Brown never planned to be a political voice. Growing up in a small town in South Jersey in the 1960s and ’70s, he aspired to be an artist. Talent ran in his family — his mother painted, and several of his siblings drew. But elevating art into a living had proven elusive, not just for his family but for Black people in general. His father, a Navy cook, encouraged Brown to get a stable job, preferably with the government. And a high school counselor discouraged him from pursuing art in college, Brown said, suggesting he would be better suited to “technical work.” That only made Brown more determined to make a living through his art.

After graduating from Stockton College (now University) in New Jersey with an art degree, he eventually worked as a graphics designer and paste-up artist for an advertising agency in Philadelphia. But he harbored a deeper ambition to express himself with art and speak to Black experiences rooted in his upbringing. He loved comic books and the exaggerated heroics in movies like Super Fly, with characters taking their cues from the Black Panther Party and the Black consciousness movement of the ’60s.

“I remember Captain America, Sgt. Fury, Wonder Woman and all those white Nazi villains,” Brown said. “My brother and I did a sci-fi comic book together, and our thing was, ‘Let’s fight for what’s right!’ That spirit was formative for me.”

Brown’s first foray into cartooning was at Stockton, where he was the first editorial cartoonist for the campus newspaper. Though the political issues he addressed at that time were limited to matters like lowering tuition, it’s there that he first felt the power in being a public voice calling for change.

He relocated from Philly to Los Angeles in 1984, drawn by opportunities for animation and film work and the mild climate. As art director at a West L.A. marketing firm, he further shored up an already impressive career; as a Black man he was a rarity in an overwhelmingly white business, and in a position of authority to boot. By any definition, he had “made it.” Then came a pivot. In 1992, following the acquittal of four police officers tried for brutally beating Black motorist Rodney King, the city erupted into five days of fires and protest.

“I could see the smoke from my apartment window in Mid-City all the way to downtown,” he recalled.

The unrest shook Brown out of his career-centered complacency and made him determined to help his adopted city by focusing on young people who, he realized, had lost hope. With a modest $2,400 grant from L.A.’s Department of Cultural Affairs, Brown began fulfilling his longtime dream by developing a comic book starring the Phoenix, a winged crimefighter and mystical figure rising from the ashes and disillusionment to show young people a new way forward (in later issues that he funded himself, it was the L.A. Phoenix). Three thousand copies of the initial black-and-white comic book, which Brown printed with his own money, were distributed to libraries across the city.

The unrest shook Brown out of his career-centered complacency and made him determined to help his adopted city by focusing on young people who, he realized, had lost hope. With a modest $2,400 grant from L.A.’s Department of Cultural Affairs, Brown began fulfilling his longtime dream by developing a comic book starring the Phoenix, a winged crimefighter and mystical figure rising from the ashes and disillusionment to show young people a new way forward (in later issues that he funded himself, it was the L.A. Phoenix). Three thousand copies of the initial black-and-white comic book, which Brown printed with his own money, were distributed to libraries across the city.

For Brown, that comic was the launchpad into a whole new work world of social justice messaging, education and community building that was powered by his art. He became a kind of one-man cottage industry, taking on graphics and educational projects for organizations such as the Automobile Club of Southern California, Los Angeles Worlds Airports, the Getty Foundation, the Cultural Affairs department and the California African American Museum. He developed a comic book workshop for young people, called Tales From the Kids, and taught art and graphics for Los Angeles Unified School District high schools. And he did it all while keeping his day job.

“I always had side hustles,” Brown said, laughing. Becoming a cartoonist in 2003 was just one of those hustles. But it had historical continuity: He took over for Clint Johnson, the veteran Sentinel cartoonist who’d spent 45 years in the chair.

Brown has been at it only half that long, though given all that’s happened on the racial front the last two decades, it often feels to him like it’s been longer. He walked away from his day job years ago, he said, because he didn’t have the time for it anymore. But the real reason was that he’d found his calling — his true career. And 22 years in, it’s something he can’t imagine ever retiring from. He said he knows he’s needed.

“It’s important for me to be there for young people, to model for them,” he said. “I’ll never stop teaching, whether it’s being in a classroom or somewhere else. It’s all about inspiring the next generation.”

Copyright 2026 Capital & Main