One-third of the region’s unhoused are Black. Funding services could be a start to investing in the equality we all need, instead of seeing it as a luxury we can’t afford — or some don’t deserve.

By Erin Aubry Kaplan

Back in August, I was invited by a friend to see a play, Shelter, written and performed by Renée Westbrook, a Black woman with a long history of homelessness. The performance was held at a church in South Central Los Angeles, which is far from a proper theater; the lighting was too dim, the acoustics nonexistent. But the show was absolutely riveting. On the pulpit that doubled that evening as a stage, Westbrook fearlessly vetted all that had led to her homelessness, including discrimination, family troubles, self-doubt, struggles with money. There were triumphs, too — along the way she had earned a master’s degree, nurtured a clear talent for writing and performance. But, ultimately, she failed to break free of a tangled web of realities that kept her on the street and on the move. Inspired as the show was, it did not have a happy ending.

Join our email list to get the stories that mainstream news is overlooking.

Sign up for Capital & Main’s newsletter.

And yet, according to Ryan J. Smith, Shelter did succeed in doing something important. “The power of story is critical — it’s what we need,” said Smith, executive director of St. Joseph Center, a grassroots homeless service and support center in Venice. “With so many Black issues, including homelessness, we all love to talk data, data, data. But data lacks context. It lacks story.”

Smith is active in the campaign to pass Measure A, the Nov. 5 county initiative to fund housing and services such as mental health treatment. (Smith knows of what he speaks; as a teen, he and his mother got a 10-hour eviction notice from their Culver City home and were forced to live in their car before finding shelter with friends.)

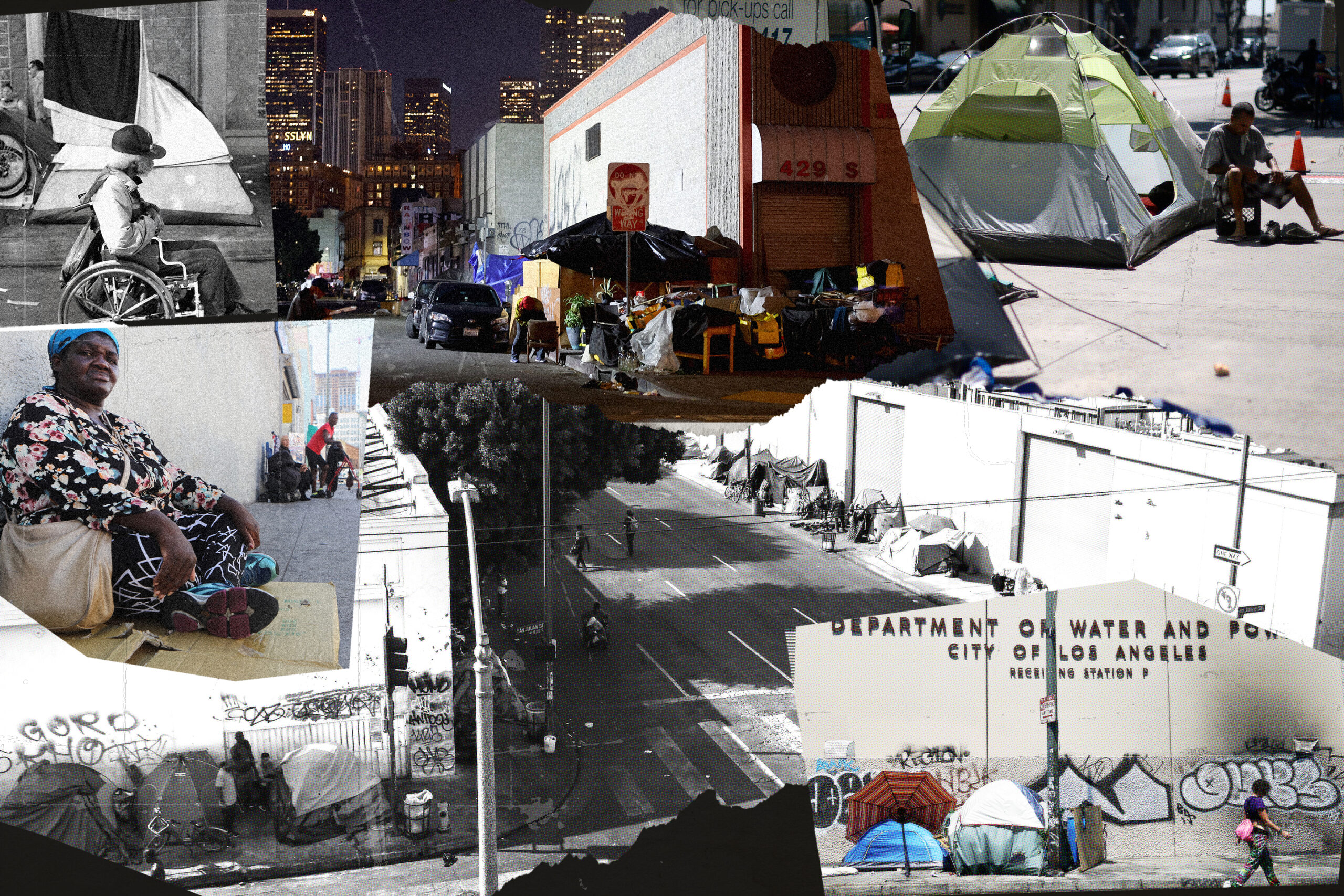

That homelessness is indeed a Black issue has been routinely missing from endless discussions about what’s become the defining urban crisis in the era of inequality. California has a third of the nation’s unhoused, roughly 181,000 people. About 75,000 are in Los Angeles County, and of those, about 25,500 are Black.

Encampments are now everywhere, in every neighborhood in L.A. The new ubiquity of homelessness has made the Black component very clear: African Americans comprise about 34% of the homeless, even though they represent only 9% of the population of Los Angeles County and shrinking. Smith said the overrepresentation goes back to the early ’80s, when homelessness started becoming a phenomenon as Reagan-era conservatism began whittling away civil rights initiatives and shredding social safety nets. Now, like so many other crises, homelessness is at an inflection point.

The needle finally seems to be moving — slightly — in the right direction. The Los Angeles Housing Services Authority reported that the number of people experiencing homelessness in the city of Los Angeles this year has dropped 2.2%, while homelessness in L.A. County overall fell by 0.27%. That’s basically unchanged, but the first time since 2018 the total did not go up.

The modest improvements could be credited to Mayor Karen Bass’ intense focus on the issue, and to the cumulative effects of Measure H, the county’s one-quarter-cent homeless services sales tax approved by voters in 2017 but set to expire in 2027. Measure A seeks to double that tax and to keep it until or unless voters decide to end it. While the initiative is expected to pass, polled voters have expressed a wariness about paying but not seeing enough results. It’s understandable: Despite this year’s good news, homelessness since 2017 — since Measure H was passed — has increased in L.A. County by an alarming 37%.

The slow and somewhat unpredictable pace of change is not surprising. Smith admitted that because the root causes of homelessness are multiple and have evolved over decades, the fix will be expensive and long term, two things voters don’t like to hear. On the other hand, the willingness of voters to invest in solutions is a sea change.

As a cause, eradicating homelessness is a hard sell. It’s telling that neither presidential candidate has talked openly or empathetically about poor people, much less about poor Black people; for too long the latter group has been the most invisible of the invisible, the “caste of our caste,” as Smith put it.

But the homelessness crisis has us in a bind. We all desperately want it to go away, to get it out of sight, but Smith said that street-level change can happen only if we go deep and seriously address the wealth gap, high cost of housing, addiction, mental health, lack of decent jobs — and, of course, the systemic racism that has made all of these things, which are destabilizing for anyone, absolutely catastrophic for Black folks.

The upcoming election will not likely rebuke that racism. The willingness to take up the cause of homelessness is countered by other ballot measures that, in the longer term, could drive more homelessness by sending more people to prison.

It is yet another tough-on-crime moment in California: George Gascon, the Los Angeles district attorney elected four years ago on the strength of his reputation as a criminal justice reformer, is on the verge of being voted out for the same reason, a fate that has already befallen former San Francisco D.A. Chesa Boudin, who was recalled by voters in 2022. Proposition 36 is a state measure that would restore some of the tough sentencing for drug and property-theft crimes voters overturned 10 years ago with Proposition 47.

These moves could ultimately increase mass incarceration and lead to more formerly incarcerated people struggling to find employment — a leading driver of Black homelessness. This retrenchment is happening at the same moment that proponents of Black reparations are beginning the historic process of trying to turn two years’ worth of research and recommendations (including recommendations around housing justice) into California law.

Yet all the political noise can obscure the need for another revolution that needs to happen, an internal one that’s more essential than any laws. Smith is convinced that Black people have to recast homelessness as their crisis, to truly embrace the least fortunate among them as fellow travelers. “This is our story,” he said, one that goes well beyond services like providing food or even temporary shelter.

It’s a shift in perspective aimed at bridging the divide between the Black middle class and working class, a subset of the larger wealth gap that isn’t just about a disparity of wealth, but a rift in community and a shared sense of destiny. Housing — homefulness, if you will — was always a big part of that. Black people have lost the housing capacity of generations past; homes that were once relatively abundant and affordable to Black people of moderate incomes, even in the midst of segregation and redlining, feel out of reach today. Nor has the middle class recovered from the 2008-09 economic crash, when Black people nationwide lost more housing-related wealth than any other group.

All of it contributes to Black anxiety about their tenuous hold on the American dream, anxiety that can be triggered by the seemingly intractable plight of the unhoused.

Smith said the anxiety is misplaced. “It almost feels like Black people are ashamed, but it’s not our shame to bear,” he said. “We talk about slavery as Black history when it’s really white history. It’s the same with homelessness. Systems are created and designed this way. It’s not our fault.”

Smith says the hope is that Measure A will move things upstream, to prevention as opposed to dealing with the existing crisis. He noted that the vast majority of Measure H funds go to simply getting people off the streets, with only a small percentage used for rental assistance and other services aimed at preventing homelessness. Measure A, he said, will help change that equation at precisely the right moment. Though the real shift isn’t monetary, it’s in how we see the unhoused, particularly the Black unhoused, not as problems to erase or even to solve, but as people to nurture. It means seeing them as fellow Americans who’ve borne the brunt of our deep-seated unwillingness to actually practice equality instead of seeing it as a luxury we can’t afford.

It means seeing. Shelter made Renée Westbrook brilliantly visible in a way that touched everyone sitting in the pews that night, including me. Afterwards she was showered with accolades. But when it was all over, she had to figure out where she was going to spend the night.

Copyright 2024 Capital & Main