Latest News

What Does the End of Forbearance Mean for California’s Homeowners?

Not all homeowners will be able to benefit from $1 billion relief program.

A program that allowed some 7.6 million homeowners across the country to press pause on their monthly mortgage payment during the COVID pandemic came to an end in late September. The wave of foreclosures that some initially feared has not materialized, but thousands of California homeowners are nonetheless contending with the debt that piled up as they dealt with unemployment or ill health. They also must grapple with their mortgage servicers, the financial middlemen charged with collecting that debt on behalf of the banks and investors that own the loans.

Connie Der Torossian, executive director of Homeownership OC, is an Orange County-based housing counselor who helps homeowners figure out ways to stay in their homes and safeguard their credit.

“We had lots of people who had been on forbearance for over a year, and we can’t make the numbers work,” said Der Torossian. The holidays provided some reprieve from foreclosures, but she expects that to change.

One-third of those who applied for forbearance are Black or Latino, yet they make up less than one-fifth of mortgage borrowers.

Now, help for Californians has arrived in the form of a $1 billion federally funded program that will allow homeowners to write down principal on their loan. But will it be enough?

During a virtual press conference held in early January to tout the launch of the California Mortgage Relief Program, Congresswoman Maxine Waters said she was concerned from the very outset that “the devil was going to come due” when the loan forbearance wound down. Last March, Congress allocated $10 billion to states to help homeowners avoid foreclosure. The newly rolled out California mortgage relief initiative, the third in the country to launch, is expected to help 20,000 to 40,000 borrowers pay off mortgage debt. It provides as much as $80,000 per household on mortgages that meet certain income and eligibility thresholds.

Waters’ South L.A. district was ravaged by the 2008-2009 foreclosure crisis, and many Black and Latino families were stripped of generational wealth. Those populations have remained vulnerable during this period. One-third of those who applied for forbearance are Black or Latino, yet they make up less than one-fifth of mortgage borrowers, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

But not all homeowners will be able to benefit from the program. State officials expect to receive two applications for the California Mortgage Relief Program for every one award.

“That program doesn’t cover all different types of foreclosures. It doesn’t deal with all the different debts that can cause foreclosure. It doesn’t cover all homeowners who are facing foreclosure. It doesn’t completely fix the problem. So I do think we’re going to see an increase in sales,” says Gina Di Giusto, a senior attorney at Housing and Economic Rights Advocates, a nonprofit legal services and advocacy organization in Oakland.

“Without access to direct aid, these homeowners are at risk of mortgage delinquency and default, foreclosure and displacement.”

~ California Attorney General Rob Bonta

And that’s not the only challenge facing homeowners. Just 25% of the state’s 361 licensed mortgage servicers are participating in the program to date. And some of the largest mortgage servicers in the country have joined only in the last two-and-a-half weeks, including New York-based JPMorgan Chase, Pennsylvania-based NewRez LLC and New Jersey-based PHH Mortgage Corporation, a subsidiary of Ocwen Financial Corporation.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta sent a letter to mortgage servicers early this month urging them to hurry up and participate in the California Mortgage Relief Program. “Without access to direct aid, these homeowners are at risk of mortgage delinquency and default, foreclosure and displacement,” he wrote.

Indeed, some homeowners were not able to hold out for the federal assistance to be made available, said Der Torossian. “We did have a couple of them that couldn’t wait, and they just ended up selling their properties.”

Estimates of homeowner hardship vary. The portion of California mortgage holders who were delinquent or in foreclosure in late December was 3%, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association, or about 150,000 homeowners. More than 500,000 California homeowners were behind on their mortgage payments in the early fall, according to a monthly survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. California has the second-lowest homeownership rate among U.S. states, just behind New York.

Conditions in California are nothing like what they were at the height of the foreclosure crisis, when as many as 15.7% of California homeowners were behind on their mortgage payments. After the housing market collapsed in 2008, many homeowners, particularly those who had received predatory loans, owed more to their lender than their house was worth.

“Business-wise, it makes sense to foreclose on people right now, when the home values are high.”

~ Julie Villalobos, bankruptcy attorney

Now the vast majority of homeowners have equity in their homes. “This means that most borrowers will have an opportunity to sell their house at a profit rather than lose everything to a foreclosure auction,” Richard Sharga, executive vice president of RealtyTrac, told Attom, a real estate industry publication.

Having equity is good for preserving wealth. But it could make it harder to hold onto a home in California’s high-priced real estate market than it did during the foreclosure crisis, notes Julie Villalobos, a bankruptcy attorney with Oak Tree Law in Los Angeles.

Absent federal assistance, there may be less incentive for the investors who own the loans to work out a loan modification. “Business-wise, it makes sense to foreclose on people right now, when the home values are high,” Villalobos said. “The bank knows in a heartbeat in this climate in this market, they can sell that house and could have every penny owed to them.”

The message she is hearing from mortgage servicers, which represent those investors, is either that the equity in her client’s home is too high for a loan modification — or that they cannot lower the payments because their interest rates are already “super-low,” based on a prior loan modification.

In the interview held in mid-January, Villalobos said she had about 10 foreclosure dates scheduled for clients in her office in the previous eight weeks compared to one or two during the entire period of the forbearance. Some clients are moving out of California.

“I’ve had about five clients in the last year sell their home during the pandemic and they moved out of state. One went to Florida. One went to Arizona. Another one went to Texas. Another one was Idaho,” she said.

“It’s not fun living paycheck to paycheck. We’re tired of being house broke.”

~ Robert Salazar

Robert Salazar is one who is leaving the state. His wife, Elena, was off her job staffing a hospital weight loss surgery unit for six to eight months during the pandemic. The couple received six months of forbearance from their mortgage servicer before filing for bankruptcy. In December, they decided to sell the house they purchased together three years ago and move to Arizona, where the cost of living is lower and they have family. A truck driver for In-N-Out Burger, Salazar, who is 50, was able to secure a transfer from his employer.

The couple received seven offers on their house in Beaumont in mid-January and accepted one that was $25,000 above their asking price. He’s looking forward to the move, which comes at a good time. His stepson just graduated from high school. “It’s not fun living paycheck to paycheck,” Salazar said. “We’re tired of being house broke.”

But Di Giusto said that many of her Bay Area clients, who are seniors and have disabilities, lack the resources to move out of state. They may have purchased their homes in the 1970s, and they would now face rents that often exceed what they were paying on their mortgage. “Their network is here,” said Di Giusto. “The No. 1 thing they’ll ask is, ‘Where are we supposed to go?’”

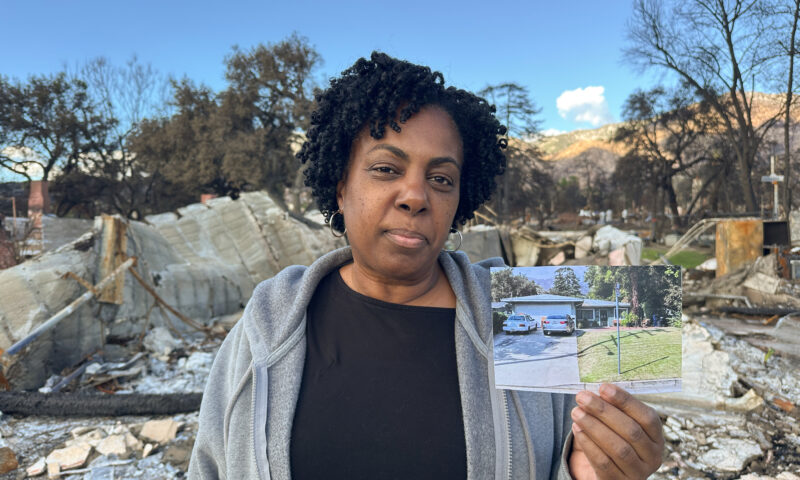

Santa Monica resident Guy Hart is battling his mortgage servicer in court in an effort to keep his home of 23 years. Photo: Jessica Goodheart.

The borrowers who are hardest to help, say advocates, are those whose loans are not backed by the federal government. Private loans account for 30% of mortgages. They typically go to borrowers with higher credit scores and incomes who have sought loans considered too large to be sold to federally chartered Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They also include those with “dings in their credit history,” according to Laurie Goodman, a fellow with the Urban Institute. Di Giusto says the borrowers she sees are economically diverse, and they are all struggling.

“All sorts of things happen. Loans get pooled and sold,” Di Giusto said. Sometimes a borrower will take out a private mortgage on a house that’s been in the family for generations.

If loans are backed by Freddie Mac or Fannie Mae or by the federal government, borrowers cannot be required to repay their debt as a lump sum when forbearance ends. They may be able to defer the missed payment(s) until they pay off their loan when they sell or refinance their mortgage or modify the terms of their loans.

“But for anybody who doesn’t have a government-backed or government-insured loan, it’s been a real struggle,” said Di Giusto.

Those private loans are part of bank portfolios, and those banks will often determine what type of relief they can offer. Private loans are sometimes owned by smaller investors or are packaged into private-label securities, and the mortgage agreements dictate the loan terms, MarketWatch reported last year. Of course, all mortgage servicers must abide by federal and state consumer protection laws no matter what kind of loan they are servicing.

Guy Hart, who lives in a condo in Santa Monica, does not have a federally backed loan. His income dipped during the pandemic when the tenants in the duplex he owns as an investment property fell behind on their rent. He complied with the eviction moratorium and kept his tenants housed. Meanwhile, his servicer, Irvine-based Rushmore Loan Management Services, gave him only three months of forbearance on a condo that he bought for $330,000 in 1998. Rushmore began foreclosure proceedings against him last April, according to legal filings.

Rushmore denied Hart’s request to extend his forbearance without providing a reason, an alleged violation of a recently enacted California law that also applies to privately owned home loans, according to a lawsuit Hart filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court.

Hart said he filled out paperwork in order to secure a loan modification, only to be told by Rushmore that the company had never received it. “I sent it to them. And they kept calling me saying, Oh, we never got it,” said Hart. His lawsuit also accuses Rushmore of violating consumer protection laws by illegally attempting to foreclose on him while his loan modification application was pending.

A spokesman for Rushmore declined to comment on Hart’s case, citing privacy laws.

Hart is not alone in finding fault with his mortgage servicer over the past two years. Complaints against mortgage companies jumped more than 60% during the pandemic compared to 2019, according to data from the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation. A spokesman for the department said via email that most of the 2,169 mortgage-related complaints in 2020 and 2021 were connected to companies’ loan servicing activity.

Hart is in arrears by approximately $40,000 on the condo, said Sarah Shapero, his attorney. After he took Rushmore to court in October, the company offered him a modification that involves increasing his monthly mortgage payment by $700 for 33 years. “They are seeing an opportunity to take much more money from him through a modification or they will simply foreclose on him because he has equity in the property,” Shapero said. He rejected the offer.

He fought off foreclosure years ago but was current on his mortgage before COVID struck. “I love the place and have worked really hard to get it and to maintain it,” says Hart, who is 55. “I don’t think because of the pandemic and everything that transpired that I should be punished for that.”

Yet he knows that he has more resources than most. Not only has he been able to hire a lawyer, he helped found a nonprofit that fights to protect seniors from financial predators. “A regular citizen or an elder — there’s no way their home would not have been sold,” he said.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

-

Pain & ProfitNovember 3, 2025

Pain & ProfitNovember 3, 2025Despite Vow to Protect Health Care for Veterans, VA Losing Doctors and Nurses

-

Column - State of InequalityNovember 6, 2025

Column - State of InequalityNovember 6, 2025Congress Could Get Millions of People Off of SNAP by Raising the Minimum Wage, but It Hasn’t — for 16 Years

-

Latest NewsOctober 31, 2025

Latest NewsOctober 31, 2025Pennsylvania Gas Producer Sues Capital & Main Over Its Reporting on Health Risks

-

The SlickNovember 5, 2025

The SlickNovember 5, 2025The David vs. Goliath Story of a Ranching Family and an Oil Giant

-

Latest NewsOctober 31, 2025

Latest NewsOctober 31, 2025People With Disabilities Struggle to Secure Accessible Housing After Disasters Like the L.A. Fires

-

Column - State of InequalityOctober 30, 2025

Column - State of InequalityOctober 30, 2025Desperate Times: ‘If We Do Not Do This … There Will Be Tragedy After Tragedy.’

-

StrandedNovember 7, 2025

StrandedNovember 7, 2025U.S. Deports Asylum Seekers to Southern Mexico Without Their Phones

-

The SlickNovember 14, 2025

The SlickNovember 14, 2025Can an Imperiled Frog Stop Oil Drilling Near Denver Suburbs? Residents Hope So.