Culture & Media

Redemption In a Bleak Universe: ‘Bars and Measures’ Reviewed

Bars and Measures, Idris Goodwin’s moving drama, directed with a sure hand by Weyni Mengesha, can be appreciated on several levels. To begin with, it’s a political work, a disturbing tale involving the questionable prosecution of an American Muslim for abetting a terrorist organization.

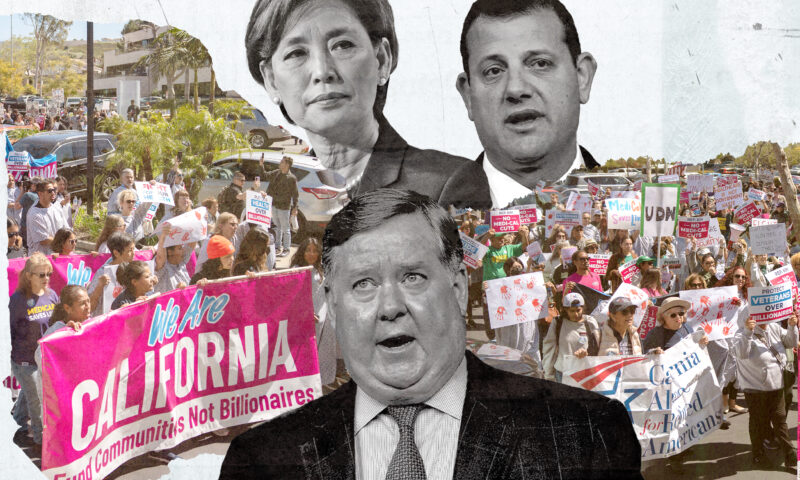

Matt Orduña, left, and Donathan Walters. (Photo: Ed Krieger)

Bars and Measures, Idris Goodwin’s moving drama, directed with a sure hand by Weyni Mengesha, can be appreciated on several levels. To begin with, it’s a political work, a disturbing tale involving the questionable prosecution of an American Muslim for abetting a terrorist organization. Second, this is a story about family, and centers on the relationship between two brothers, whose bonds of affection hold strong despite their differences in personality and outlook — that is, until the harsh judgment of the outside world compels otherwise. Last, Goodwin presents us with a portrait of musicians and their art, and offers a paean to both as a redemptive gift in a bleak and desolate universe.

The brothers in question are Bilal (Matt Orduña), a brooding jazz musician, and Eric (Donathan Walters), his younger brother and a much sunnier individual who’s been to Julliard and is now building a career as a classical pianist. The play opens in the visiting chamber of a prison, where Bilal is being held prior to his trial for aiding a terrorist group with a large sum of cash donated through his mosque. The brothers are passing their time together practicing a riff which Bilal has been teaching to Eric, to be performed at a fundraiser for Bilal’s defense.

During their interchange, and supplemented by narration from Eric, who is Christian, we learn something of their background, including details about their deceased father, a steady and dutiful provider, along with Bilal’s religious conversion and transformation from a pugnacious brawler into a devout individual, struggling to submit, as enjoined by his religion, to God’s will.

As a prisoner, Bilal gets a lot of practice in the latter, continually having to withstand the taunts of a spiteful guard (Brian Abraham), and to endure the pain of an isolation cell, to which he’s been consigned. To weaken him, he’s served non-Halal foods that he will not eat, so that’s he’s forced into a fast not of his choosing.

But for a while the harshness of his environment is mediated by music, and by Bilal’s opportunity to share with his brother — and the audience — the fruits of his talent.

Much of this work’s power reflects off the intensity of Orduña’s performance. It draws you in from the start, and transports you with him to the end. Walters, whom I favorably reviewed twice last year in cheerier roles and sillier plays, here displays real depth as a dramatic performer. Like jazzmen attuned to each other’s rhythm, these two performers interact with kinetic grace as the piece builds to its powerful catharsis.

Perhaps what’s most notable about the play itself is how well the writer has intermingled the disparate threads of his story. In this production, the musical elements of Goodwin’s tale are subtly but splendidly underscored in the bar-shaped video projections on the back wall that seem to pulse like chords, or call to mind the sharp keys on a piano. No videographer is mentioned, so I’ll credit scenic designer Francois–Pierre Couture for this, as well as lighting designer Tom Ontiveros. Throughout, John Nobori’s sound is aerial and haunting.

The Theatre@Boston Court, 70 N. Mentor Ave., Pasadena; Thurs.-Sat., 8 p.m.; Sun., 2 p.m.; through Oct. 23. (626) 683-6883 or www.bostoncourt.com

-

Striking BackApril 10, 2025

Striking BackApril 10, 2025USC Follows Amazon and Musk’s SpaceX in Calling Labor Board Unconstitutional

-

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025

Latest NewsApril 9, 2025Democratic and Republican Lawmakers Work to Undermine Voter-Backed Wage and Sick Leave Laws

-

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025

Latest NewsApril 28, 2025A Majority of Californians Support Affordable Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants, Polls Show

-

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025

Latest NewsApril 11, 2025California Showdown Over Medicaid as GOP Approves Massive Cuts

-

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025

Column - California UncoveredMay 5, 2025How Did Farmers Respond When the Trump Administration Suddenly Stopped Paying Them to Help Feed Needy Californians?

-

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025

Column - State of InequalityApril 11, 2025California State University’s Financial Aid Students Learn Chaos 101

-

The SlickApril 30, 2025

The SlickApril 30, 2025Fracking-Powered Crypto Mine in Pennsylvania Shuts Down Without Word to Regulators

-

The SlickApril 16, 2025

The SlickApril 16, 2025In Colorado, Gas for Cars Could Soon Come With a Warning Label