Labor & Economy

Daring to Dream: Portrait of a Port Driver

It’s 5:45 a.m. on Wednesday morning and it’s been a long night for Dennis Martinez and his fellow port truck drivers.

Martinez is nearing the end of a 48-hour strike against Total Transportation Services, Inc. (TTSI), the logistics company for which he has worked for two and a half years. The drivers are about to go through the toughest part of the two-day action – asking the company they have been striking against if they can return to work.

The fatigue shows on Martinez’s face. He hasn’t gotten much sleep but he expected that. He knew taking on a wealthy company wasn’t going to be easy.

A slender man dressed in a gray Aero sweatshirt, jeans and tennis shoes, Martinez is 29 but can pass for a teenager. He keeps headphones in his right ear just in case he needs a pick-me-up from Daddy Yankee and Pit Bull, two of reggaeton’s biggest artists. He’s not smiling. Smiles, at least lately, are mainly reserved for his wife and children. Instead, he wears a determined expression.

Martinez and several co-workers walk over to TTSI’s dispatch office at the company’s headquarters, a large and shiny modern white building located in an industrial strip of Rancho Dominguez. They face the dispatch manager, who just days earlier was photographing the men picketing in front of the building.

The manager responds to their request to go back to work with a sarcastic, “Oh, now you want to work?”

He tells the drivers that if there is work, they will work. If there isn’t work . . .

The manager turns to Martinez.

“You’re a night driver,” the manager says. “Come back at four this afternoon to check if there’s work.”

The men leave but are quickly surrounded by a crowd of their allies who have gathered from around the region and the country for the largest port truck driver strike to date. There is a lot of handshaking.

Port Truck Driver interview by Ana Beatriz Cholo from LAANE on Vimeo.

Fredrick P. Potter Jr., who flew in from New Jersey, profusely thanks the group. He is a vice president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and director of its port division. Standing next to him is Eric Tate, the secretary-treasurer of L.A.’s Teamsters Local 848, which is backing the strike.

“They’re standing up for their rights this week,” Potter said, holding a cigar in his hand. “It takes a lot of courage. These guys put their livelihood on the line. They just want what’s fair.”

Minutes later, someone shouts: “We got a container! They gave them a load. They’re going to give them some loads.”

It’s progress. A few of the morning port truck drivers are going to get some work.

More than 100 truck drivers from three different trucking companies took part in the action earlier this week. (Besides TTSI, drivers struck Pacific 9 Transportation and Green Fleet Systems.) The employees say they have been misclassified by the companies as “independent contractors” — a classification that results in drivers getting lower pay and no workplace protections. They have filed claims against all three companies with the state for wage theft.

There are a total of 44 pending California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE) claims against TTSI, a logistics company owned by Vic La Rosa. It is one of the top 10 trucking companies serving the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach; the firm’s key customers are Target, J. Crew, Polo, Ralph Lauren and Home Depot.

On Sunday, the day before the strike, Martinez was at home in a sunny, two-bedroom apartment that he shares with his wife and two kids in a quiet, working-class Watts neighborhood. The apartment is sparsely furnished and decorated with family photos.

Francis, Dennis and Dominick Martinez

His wife, Francis, was going to a baby shower in the afternoon. She was cradling the couple’s youngest child, nine-month-old Dominick. Their nine-year-old son Christian sat close by. Martinez has two other children who live with their mother in Corona.

“We have been waiting for this to happen for a long time,” Martinez said in his halting English.

His story in the United States began a decade ago when he moved from Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, and joined his mother who was already living here. He took ESL classes at a community college, worked at a Target warehouse for a couple of years, went to work for a Toyota car dealership as a parts salesman but got laid off in 2009. He didn’t have a job for six months and had to move back in with his mother. His stepfather encouraged him to get a commercial driver’s license. Martinez learned to drive a big rig, spent two years on the road and has driven through 48 states.

He never had an accident and only got one ticket the entire time.

Short-haul driving began well for him at TTSI, which gave him a truck the company claimed was new — despite the 140,000 miles on its odometer. Like other so-called independent contractors, Martinez was responsible for the truck’s lease payments, insurance, parking, diesel fuel and repairs. His routes took him from Long Beach to Fontana or San Bernardino, and sometimes he made longer trips to Nevada, San Francisco or Bakersfield.

But Martinez started noticing irregularities in his pay and began asking questions. He wasn’t alone. When he, along with about 40 other drivers, filed wage-theft claims with the DLSE, the agency charged with enforcing California labor laws, the group made the case that its members were actually TTSI employees who had been misclassified as independent contractors.

Martinez is quiet and shy, but not afraid to speak up. He said the company began to retaliate against him and other drivers by piling on excessive deductions and giving drivers fewer containers to haul. Even after working a full week, Martinez has ended up owing the company money. Other truck drivers say they have encountered the same situation.

Last November, a truck driver from a different company ran into Martinez’s chassis while Martinez was waiting to unload at the Port of L.A. His truck then hit the one in front of him. Martinez ended up having to take five weeks off while his truck was being repaired. During that time he borrowed money, took out a bank loan and tried to keep up with bills.

He said when a fellow driver’s truck broke down with a repair bill of $11,000, the company tried to make the driver pay for it. The driver quit instead.

Some truck drivers have backed off from their DLSE claims after being bribed by the company with more pay, nicer trucks and better hauls, Martinez said. He doesn’t blame them.

“It’s hard,” Martinez said sitting in his living room with Francis beside him. “There are bills to pay and we’re struggling. They are doing it for their families to be okay, but they’re giving the companies the power to not respect you.”

Despite his hardships, he wants to dare to dream again, to have dreams big and small: Taking a vacation with his family to their home country. Getting health insurance. Supporting his wife, who already has a college degree from Honduras, to go back to school in the U.S.

His voice sounded shy and hesitant. He would like to go back to school, too, to study architecture and maybe to even become an architect someday. “I would have to start from the beginning,” he said hesitantly. His voice trailed off. “But I would love to.”

Martinez first approached La Rosa, TTSI’s owner, last November with a petition for drivers to be properly recognized as company employees. More than 25 drivers, a priest and a Teamsters representative joined him.

La Rosa, according to Martinez, gave his word that he would not retaliate against the drivers. But on that same day, they were put on hold for an hour when they called in to dispatch for assignments. Then, they were told to go to the port — where there would be a four-hour wait. That meant wasted time since the drivers don’t get paid by the hour, but rather, per container. If they are stuck at the port, they are not earning money, Martinez said.

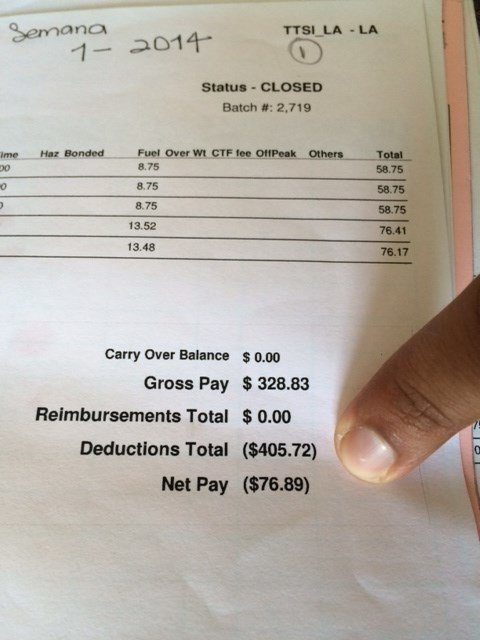

To prove his points, Martinez produced a binder full of pay records and receipts. He flipped through its pages and pointed to TTSI’s endless deductions and charges. He then pointed to the bottom line of one paycheck and questioned how a family could survive on $134.64 a week. Monthly rent is $1,200; his child support is $300 and his car payment is $600. The latter is high due to bad credit, Martinez added.

To prove his points, Martinez produced a binder full of pay records and receipts. He flipped through its pages and pointed to TTSI’s endless deductions and charges. He then pointed to the bottom line of one paycheck and questioned how a family could survive on $134.64 a week. Monthly rent is $1,200; his child support is $300 and his car payment is $600. The latter is high due to bad credit, Martinez added.

“I see this company just getting richer and taking money from their drivers,” he said.

Francis nodded in agreement and beamed at him with pride. Christian watched and listened to everything being said. He is also proud of his father and wrote a school report on their plight. He didn’t get a good grade but that’s all right, his mother said. He is very smart and his English is getting better. After all, he has only been in the U.S. for a little under two years.

“He wants to grow up and become a lawyer,” she said.

And as for her husband?

“All that he is asking is that they respect their rights and respect them as people,” she said in Spanish. “This is a country made up of laws. We, as a family, want them to stop these actions. We are very proud of him because he is acting as an example for his kids. On top of everything, he is saying that our voices count. We are asking for justice and dignity.”

But why not just quit and find another job?

“It’s not a question of economics anymore,” Francis answered. “It’s a question of morality.”

On Monday morning at 6 a.m. about a dozen workers start picketing in front of TTSI’s company headquarters. The rest are at the truck yard, another TTSI property. Dozens of other drivers are scattered in the area at various locations. Their signs are reminiscent of the “I Am a Man” placards seen during Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 labor march in Memphis. The port drivers’ signs say, “I Am an Employee.”

When a company janitor tries to get into TTSI’s parking lot, the picketers block his access. He protests and tells them he’s a contractor trying to get to work. Ten minutes later they let him in.

At 11:30 a.m., some strikers, including Martinez, head over to Wilmington Waterfront Park for a press conference.

When Martinez gets there, he walks over to a picnic table and practices what he is going to say – he has been tapped as the emcee. Martinez is nervous but his outward expression is calm. His wife, holding their daughter, comes over and sits next to him. She starts coaching him in Spanish and reminds him of why they are there.

Then Martinez confidently walks to the podium and faces television cameras, reporters, photographers, union coordinators, activists and his fellow drivers. His backdrop, looming behind him, is the Port of Los Angeles and its towering cranes.

“We are fighting these companies because we want a better future for our families and for other employees,” he says, his voice getting stronger and more confident with every word.

After it ends, he does a lengthy television interview with a Spanish-language reporter from Channel 22. A communications organizer for Change to Win, a natonal labor group that is involved in the effort, approaches him. Is he willing to be in Burbank early the next morning for a studio interview with the popular Spanish radio host El Cucuy de la Mañana?

The interview will cut into his sleep time but Martinez doesn’t hesitate. He knows many of the Spanish-speaking truck drivers listen to the popular radio show on AM 690. It’s an opportunity for him to spread their message to a wider audience. Besides, his mother is a big fan and El Cucuy hails from Honduras. It’s a win-win.

During the show, El Cucuy graciously gives Norma Castillo in Moreno Valley a “shout-out” on behalf of her son. Martinez later learns that his mother was pleased.

That Tuesday night Martinez goes back on the picket line one last time and wonders what will happen after the strike.

Will there be more retaliation? Will he get even less work?

In his mind, those questions get answered after the Wednesday morning confrontation with the dispatch manager at TTSI. Martinez is feeling somewhat pessimistic.

“Right now,” he says, “I’m thinking that they will take more retaliations against us, but I know we sent the message we wanted to send.” Martinez is standing across the street from TTSI’s company headquarters. Labor representatives and other drivers have been slowly getting into their cars and driving away.

Despite his apprehensions about the eventual outcome, he harbors no regrets.

“It’s worth it to speak about this,” he said. “It’s either I do it or I stay quiet. You saw the support of my wife and my children. That gives me the strength because, really, I’m doing it for them.”

At that moment, a fellow truck driver in a big rig slowly drives by. The two men acknowledge each other. Martinez says that this particular driver was originally a part of the claim against the company.

“But they bought him,” he says. “I believe they offered him better work in exchange for dropping his claim. He was one of the first to make the claim, but he was also one of the first to drop it.”

He goes home and gets some much-needed rest. At 4 p.m., he calls the company dispatch and receives good news. He’s got work – two containers.

“It’s a good start,” he says. And, he adds, they didn’t give him any trouble. It was all business. He starts feeling hopeful. Maybe things will start looking up.

All photos by Ana Beatriz Cholo

-

The Heat 2024April 1, 2024

The Heat 2024April 1, 2024The Way-Down-the-Ballot Races That Could Transform Energy Policy for Millions

-

The SlickApril 16, 2024

The SlickApril 16, 2024On the Chopping Block: California’s Climate Program for Low-Income Housing

-

California UncoveredMarch 18, 2024

California UncoveredMarch 18, 2024A California Program to Get Produce to Low-Income Families Is a Hit. Now It Is Running Out of Money.

-

Extreme WealthApril 2, 2024

Extreme WealthApril 2, 2024Extreme Wealth Is on the Ballot This Year — Will Americans Vote to Tax the Rich?

-

The Heat 2024March 19, 2024

The Heat 2024March 19, 2024In Deep Red Utah, Climate Concerns Are Now Motivating Candidates

-

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024Tried as an Adult at 16: California’s Laws Have Changed but Angelo Vasquez’s Sentence Has Not

-

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024‘Every Day the Ocean Is Eating Away at the Land’

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy