Education

Trouble in Eden: A Divided Marin County Community Gets a New Charter School

A new charter school in affluent Ross Valley marks the latest chapter in California’s education wars.

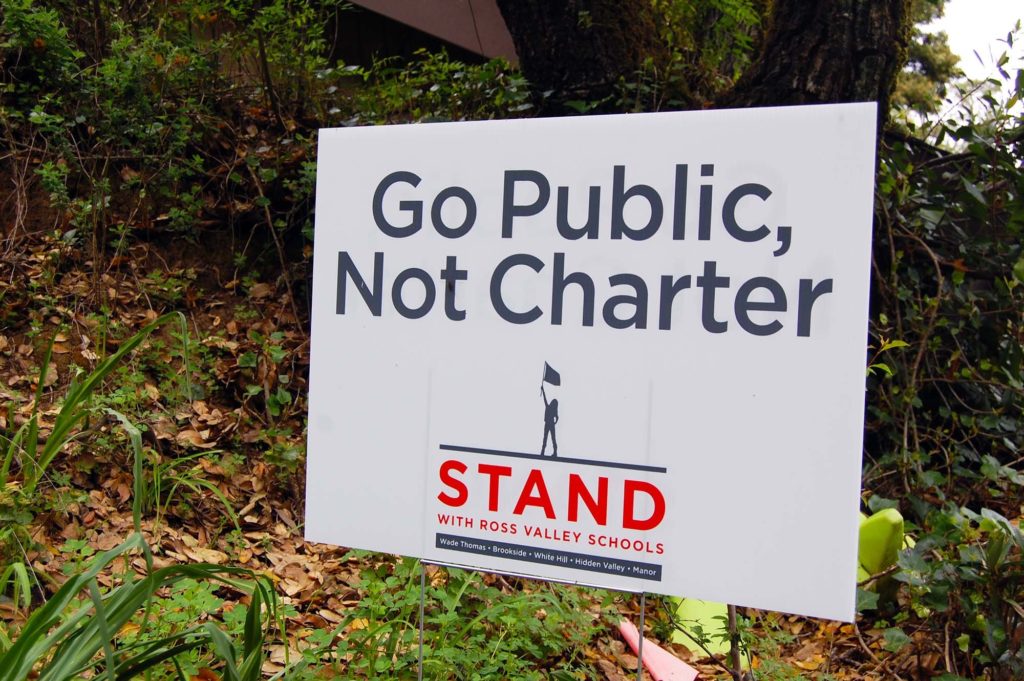

Ross Valley School District Parents. (All photos by Bill Raden)

On a recent idyllic Marin County afternoon, Manor Elementary School PTA President Heather Bennett sat on her outdoor deck and related the newest incident to inflame the Ross Valley public school community. “Crazy stuff is going on,” she said, referring to what could be the longest-running conflict in California’s education wars. The ugly and divisive fight pits STAND With Ross Valley Schools — a group of parents who favor traditional public schools — against a breakaway alternative education program soon to become the Ross Valley Charter School (RVC).

“It’s a solution to a problem that didn’t exist, and it actually creates a problem that need not exist,” Bennett said of the charter school.

The dispute, she claimed, which had until recently played out in emotional Ross Valley Elementary School District (RVSD) board meetings, contentious lawsuits and chilly encounters in local supermarkets, had escalated into heated accusations of vandalism on the neighborhood-focused social network, Nextdoor, where many of the daily salvos between the warring sides are hurled.

STAND was formed last December after the not-yet-opened charter school, which was eventually co-located at the district’s lone middle school, filed a facilities request under the aegis of Proposition 39, a 2000 law passed by California voters that compels school districts to house charters on their campuses.

California’s 1992 charter school law waived much of the state’s education code for charters, under the theory that they would be dynamic classroom laboratories capable of closing the state’s education gap for children traumatized by the poverty and social stressors of their neighborhoods. What the law doesn’t do is limit charter schools to low-performing communities, and for small, highly rated districts like Ross Valley, charter schools carry substantial costs that STAND parents maintain have already negatively impacted classrooms.

“What concerns me is that [Ross Valley Charter] is going to eventually take over one of our neighborhood public schools,” said Eileen Brown, who is a STAND member but also a former parent of RVC’s predecessor, a district-run Alternative Schools program called MAP. “They will grow and they will get enough parents to buy in, so that one of our neighborhood public schools that serves all the children is not going to have enough numbers to justify staying open.”

Besides being California’s wealthiest county, Marin is one of its best educated. The high value its residents place on a quality education has given Marin County some of California’s highest-performing and most competitive schools — including the four top-rated elementary schools and one middle school that serve the RVSD towns of Fairfax and San Anselmo.

It has also given Ross Valley a blistering charter fight, in a Bay Area community long renowned for its laidback lifestyle and 1960s counterculture past.

What has turned parent against parent, neighbor against neighbor, and even split up children’s friendships is MAP (Multi-Age Program), which was installed at Fairfax’s sole neighborhood school, Manor Elementary, in 1996. In August, the program will reopen its doors as the Ross Valley Charter School to 130 students, or six percent of RVSD’s 2,300 enrollment — becoming only the fourth charter in Marin county — in a co-location at White Hill, the district’s lone middle school.

But many Fairfax parents already had their fill of MAP when the program was allowed to operate for 18 years under its own board as, essentially, an elite private academy within the district — much like a charter school. But because MAP was co-located at Manor Elementary, which includes the bulk of the district’s English Language Learners (ELL) and Free and Reduced Price Lunch populations, it was Fairfax’s traditional K-5 students who paid a disproportionate price in resources, enrollment and especially, said the Manor parents, the program’s rigid culture of keeping the two programs socially segregated.

“We’d say, ‘Hey, you’re going to go to a solstice celebration? We wanna come,’” Bennett remembered. “And they’re, ‘Well, no, it’s just a MAP thing.’ ‘But isn’t it a school thing?’ ‘No, it’s a MAP thing.’ ‘Oh, okay.’”

Former MAP parent and RVC co-petitioner Andrea Sumits defended the separatism as what she called MAP’s “close-knit community” design. “Many families were attracted to MAP, and are attracted to RVC, because it provides that ‘small school’ environment in a public school setting,” she said by email. “For some students, the safety and comfort of a smaller school environment is crucial to their learning experience. MAP classrooms planned their own field trips, just as any classroom does.”

Long-simmering tensions came to a full boil in 2014, when formal discrimination charges by a Manor parent prompted a new school board leadership and new superintendent to rein in the program under direct district governance. Rather than cede control, the parents, teachers and ex-board trustees who comprise MAP’s leadership petitioned the State Board of Education to take the program charter.

In many ways the story of Ross Valley, located a half hour across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, is one of an affluent, liberal community belatedly waking up to the sobering realities of the “school choice” movement and a neoliberal ideology that sees marketplace competition as a cure-all, and redefines citizens as consumers even as it “hollows out” California’s most cherished of democratic institutions.

Studies continue to show that most charters don’t produce better academic results than traditional public schools, but charters do compete for the same Average Daily Attendance (ADA) dollars that fund public schools. Every new charter seat siphons off ADA revenues from the charters’ host districts, as well as burdening those districts with higher per-pupil costs incurred by the district’s fixed operating expenses.

STAND claims the cost of 152 students leaving the district for RVC to be over $1.1 million —resulting in a net decrease of over $500,000 after offsetting teacher reductions. Unlike a large district like Los Angeles, STAND parents argue, a small, budget-constrained district like RVSD will simply not be able absorb the loss without feeling pain.

Co-founded by a group that included former RVSD board trustee Sharon Sagar and parent Julie Quater, who now runs the district’s arts-enrichment foundation, MAP was modeled after Ohlone Elementary School, a multi-age alternative school in Silicon Valley. Like Ohlone, MAP was based on the Reggio Emilia project-based approach, a form of self-directed learning.

MAP’s unstructured, child-centric learning philosophy and its heavy emphasis on parent classroom involvement seemed to resonate with a minority of families that have aggressively embraced the area’s nonconformist, New Age roots. As articulated by MAP kindergarten teacher Tim Heth in an RVC promotional video, “We’re trying to create thinkers, not just traditional smart kids”

Conn Hickey, RVC’s chief financial officer who, with fellow ex-school board trustee Sagar, has been most criticized for shielding MAP from district oversight, defended MAP/RVC in an email to Capital & Main.

“Many in this affluent Ross Valley community appear to believe that if your child has difficulty in the District schools, that your only option should be private school,” Hickey wrote. “The fact that many parents in our community believe they can invent their own definition of what is a public school to fit their anti-charter narrative, is a reflection of the more troubling ‘alternate facts’ era we find ourselves in.”

One particular sore point for both Manor parents and teachers was the classroom enrollment disparities, which were partly due to MAP’s practice of what it called “gender-balancing” — insisting that each MAP classroom be evenly split between 10 girls and 10 boys.

“Some years it was pretty significant,” a Manor teacher recalled. “Seventeen girls, eight boys for me. Another year, I had 15 boys and six girls. Huge fluctuations. … At that time, we had a big bubble of population. We had kids within our boundaries that couldn’t go to our school. There wasn’t room. And it felt weird to have [MAP] have that status of being a district program when there were kids close by that couldn’t fit in our school.”

A 2013 legal review of MAP, ordered by board trustees after Hickey and Sagar stepped down, found that the gender balancing violated federal sex discrimination rules, and that the policymaking authority of the program’s governance board, in which the Manor principal could be overruled by the MAP teachers and parents, was shortchanging the school’s K-5 program.

The following year, after the formal discrimination complaint had been filed against the program, RSVD’s new superintendent, Rick Bagley, commissioned an investigation by attorney Chris Reynolds, a private investigator specializing in education cases. Reynolds found that MAP’s Advisory Board had been sequestered for years from district oversight and authority at a time that Sagar and Hickey, who would later turn up as co-petitioners for RVC, were both RSVD board trustees and deeply involved in MAP governance.

During much of its existence, the Reynolds Report said, MAP was allowed its own PTA fundraising without reporting to the district, it had a mandatory parent “volunteer” work quota policy in violation of the state’s constitutional guarantee of free public schools, and it could unilaterally change its enrollment priorities. The report found that these and other enrollment provisions, such as a required parent interview with MAP teachers prior to acceptance, or the lack of Spanish-language registration forms, created a “negative perception” of the program in the Manor community.

It also produced a student body that mirrored enrollment stratifications that have plagued other charter schools: The MAP population was whiter, wealthier and had fewer learning disabilities than that of Manor School’s general K-5 population, and by significant margins.

Though Reynolds was unable to prove selective screening or intentional discrimination, his report made it clear that responsibility lay with the practices and policies of MAP. It’s a rap that the MAP/RVC leaders have refused to accept, and Hickey was quick to insist that “the Reynolds report found the district at fault, not MAP.”

Rather than agree to governance reforms, MAP’s leadership petitioned to take the program charter.

“It’s not viable, in my opinion,” said RVSD board president Anne Capron of the new charter. Capron led the trustees in rejecting RVC’s authorization, arguing, “They didn’t budget in health and welfare coverage for the current teachers who said that they didn’t need it. That’s all fine and well until those teachers leave and you have new ones [who] need health and welfare. … They didn’t budget for any special ed private placements or additional supports or one-on-one aids or any of that. They budgeted $6 per student for supplies and books. They didn’t budget anything.”

However, the California State Board of Education brushed aside local concerns and granted RVC authorization in January of last year. The SBE seemed satisfied with Hickey’s promise that RVC would undertake what it had long resisted initiating while at Manor School — outreach to the valley’s underserved communities through ambitious recruitment targets. SBE member Trish Williams explained that California’s charter law doesn’t allow the board to consider community harmony or a program’s past record in its evaluations of viability.

“Even within a totally fabulous school district,” Williams said, “there can be a case where parents feel like they want a different kind of instructional methodology and environment for their children. … And that is also a legitimate reason for why charter schools get started.”

“I sort of understand that thinking,” Bagley countered, before asking, “What is really the benefit of this – not just to these people, but to the whole community?”

If there is a positive side to the bitter divide, it may be STAND itself, which has galvanized Ross Valley’s parents around its own schools, while raising their awareness about the vulnerability of all of California’s public schools.

“We’ve got a local nut to crack right now,” reflected San Anselmo STAND parent Kelly Murphy, “but if the Ross Valley Charter folds for whatever reason, we’re not going to stop standing. We are committed to helping other communities that are facing this challenge. We want to work together to see if we can tackle this at the state level. We’re not going anywhere.”

-

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024The Transatlantic Battle to Stop Methane Gas Exports From South Texas

-

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024A Whole-Person Approach to Combating Homelessness

-

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024Street Artists Say Graffiti on Abandoned L.A. High-Rises Is Disruptive, Divisive Art

-

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024Dispelling the Stereotypes About California’s Low-Wage Workers

-

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024An Author Reflects on the Effort to Rebuild L.A. After the ‘Violent Spring’ of 1992

-

State of InequalityMarch 28, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 28, 2024Los Angeles Hotel Workers Could Use the 2028 Olympics to Their Advantage

-

Striking BackApril 12, 2024

Striking BackApril 12, 2024Organizing the Slopes

-

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024

State of InequalityApril 25, 2024California Often Leads Change, but Not for Single-Payer Health Care