Labor & Economy

California’s Affordable Housing Crisis: Warnings and Solutions

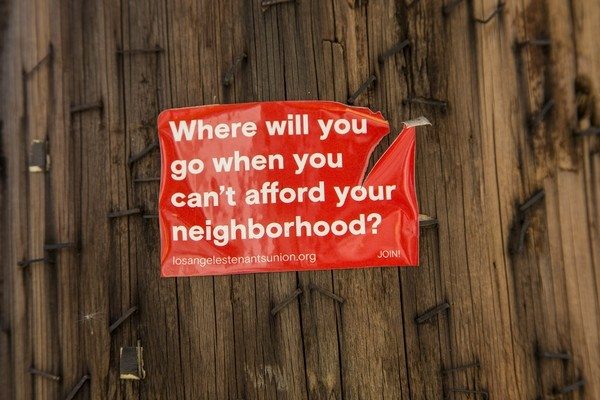

California leads the nation in having the most severely rent-burdened households, as well as having the largest shortage of affordable rental homes. (The U.S. Department Housing and Urban Development and other agencies consider families that spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent as rent-burdened.)

California leads the nation in having the most severely rent-burdened households, as well as having the largest shortage of affordable rental homes. (The U.S. Department Housing and Urban Development and other agencies consider families that spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent as rent-burdened.)

Buying a house within a reasonable commuting distance in the Golden State – even for stable, employed middle-class families – is fast becoming out of reach.

The reality is even worse for renters: From San Francisco and Silicon Valley, to San Diego and the coastal cities in between, California’s 2.2 million low-income households compete for only 664,000 affordable rental homes. This leaves more than 1.5 million of California’s poorest without access to affordable housing in a state with 21 of the 30 most expensive rental housing markets in the country, according to a recent report from the private, nonprofit California Housing Partnership Corporation.

“We were already in a hole — now it’s exacerbated, particularly in the coastal areas,” Carol Galante told Capital & Main in an interview.

A former assistant secretary in President Obama’s Department of Housing and Urban Development, Galante now directs the newly-formed Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley. There, she seeks viable options for low- and medium-income workers who are looking for a reasonably priced place to call home.

“We have a long-term history in the state of not keeping up with our growing economy,” she said, pointing out that half a million post-recession jobs created in the Bay Area have been met with a mere 50,000 new housing units that have been built or permitted.

Housing advocates say their most daunting challenge is creating a permanent funding source. Before 2011, when Governor Jerry Brown and the state legislature disbanded them, community redevelopment agencies were the main source for funding affordable housing. The agencies allowed cities and counties to devote more tax revenue to development. Advocates have yet to discover ways to make up for the estimated $1.5 billion loss. (There’s no talk of reviving the agencies.)

Assembly Bill 1335, introduced last year by Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), would have established a permanent source of funding for affordable housing by placing a $75 fee on real estate transaction documents, excluding home sales. It never made it out of the Assembly.

Another measure, AB 35, proposed to increase the state’s annual low-income housing tax credit by $100 million each year for five years, and would have aided in the creation of affordable housing for low- and very low-income renters. Authored by Atkins and Assemblymember David Chiu (D-San Francisco), the bill managed to do the almost unthinkable in this polarized political climate — it garnered the support of a broad coalition that included numerous government and nonprofit organizations. The California Chamber of Commerce even named it a “jobs creator bill.”

But Brown vetoed it.

Atkins, considered to be affordable housing’s loudest voice in the state legislature, is not easily dissuaded, however, and vows to press for a permanent source of funding. She asserts that housing affordability is at the heart of all of California’s most important issues: the economy, business attraction and retention, poverty, education, transportation, climate change.

“The economy is rebounding nicely,” Atkins said, “but the recovery hasn’t reached many middle- and working-class residents, and especially the poor. Housing instability hits low-income residents the hardest, but rising housing costs affect everyone. Without plentiful and affordable homes near jobs, it’s harder for companies to attract and retain employees.”

Toyota’s decision to move its North American headquarters from Torrance, located in Los Angeles County’s South Bay region, to Plano, Texas perfectly illustrates Atkins’ point. Business journals recently reported that housing costs played a role in the automaker’s decision. In Torrance, the median home costs $508,000, with the median income at $76,000. In the Dallas-Fort Worth area near Plano, the median income is $58,000, but the median house cost is $210,000.

One of the oldest organizations studying the housing crisis is the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, a public policy business trade organization created in 1978 by Hewlett-Packard co-founder David Packard. Today it represents nearly 400 companies in the region. The group founded a private fundraising effort called the Housing Trust Silicon Valley. Amanda Montez, the leadership group’s senior director for housing and community development, argues that solutions exist but that many of them depend on the will of the legislature and the governor. The state could do much more, she said.

When Governor Brown vetoed what she called modest attempts to alleviate the housing crunch, “he missed a huge opportunity.”

“It’s going to require some deft political maneuvering to make enough affordable housing a reality,” said Montez. “It takes local, state and federal resources, banks, private money, public money. What’s often lost in that conversation are the human beings who don’t have a place to live.”

But money is not enough, Carol Galante said. Projects must get approved and politically motivated local zoning boards often get in the way. If a resident already has a nice home with off-street parking, they may not feel particularly inclined to have their city council or local planning agency build affordable homes across the street.

When some people think of affordable housing, they envision barracks-style apartment complexes, rampant crime and drug deals taking place on stairwells and street corners. The reality is that your son’s college professor or the barista who served up your coffee this morning may well live in affordable housing units, which often blend in seamlessly with other homes.

In the last decade, rents have risen dramatically while wages have been stagnant or lost ground. Many lower to middle class families are unable to afford what the housing market is currently providing.

Jermaine Jackson lucked out last year when he landed one of the 88 units set aside as affordable housing at One Santa Fe, the massive new apartment complex located in Los Angeles’ hip Arts District. The actor, whose resume is filled with TV and commercial gigs, has a day job working at the Los Angeles Region American Red Cross certifying people in CPR.

His modern, one-bedroom apartment features hardwood floors, stainless steel appliances and a balcony view of downtown – all for $765 a month. For tenants paying the market rate, the rent is nearly triple what he’s paying.

When he walked into his unit for the first time right before Christmas in 2014, he broke down. “I really started crying. Picture a grown man crying and wondering, “Is anyone looking?”

But it took Jackson close to two years to get the coveted apartment. He had called the 134-year-old Actors Fund, and asked for assistance in finding a safe place to live. Rent was going up on his North Hollywood studio and the routine gunshots and rampant prostitution in the area made it an undesirable place to live.

“They said there might be some opportunities for affordable housing,” the Georgia native said. “I didn’t know anything about it. I had only heard of Section 8.”

First, he entered the lottery to get into a building close enough to catch the ocean breeze in Santa Monica. He didn’t get it. Then he went through the tedious process again with another building in an up and coming area off Western Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard. He received a move-in date but a glitch in paperwork made him ineligible.

Jackson’s third attempt was the charm that got him into his current, shiny new unit.

But homeowners can be finicky about the individual moving into the affordable housing unit next door and how it will affect their day-to-day lives.

“There’s this fear that affordable housing will affect your property values,” Galante said. “How do we get people who aren’t engaged to recognize that affordable housing matters to everyone? That is why in my view, you need to get above the fray. It is way too easy for these local NIMBYs to delay, add costs and shut down new developments.”

Ask affordable housing advocates for one silver-bullet solution and you’ll soon hear many possible solutions — and none of them simple. Ideas range from the practical to the very ambitious:

- With community redevelopment agencies abolished, create a permanent source of funding for housing.

- Build inexpensive, “tiny houses” and redefine the notion of how much space one actually needs to live comfortably.

- Increase state tax credits.

- Incentivize large corporations or school districts to build employee housing, as did Santa Clara’s, which in 2002 built Casa del Maestro (House of the Teacher), a small apartment complex for teachers in this pricey community. It only made a dent in the overall housing needs for educators in the region.

- Cut overly burdensome city regulations that often hamper housing developers from producing affordable housing.

The list goes on, but what’s holding up any progress, many housing advocates claim, is a lack of political will that extends from the statehouse to the local level. In the meantime, some cities are adopting housing impact fees.

Last November San Francisco voters passed Proposition A, a $350 million bond measure, with about $60 million of it allocated to provide middle-income housing – “to not only help people on the lowest band of the income spectrum but also setting some money aside for middle-income housing,” said Galante.

One very different model that Galante and others find promising is Massachusetts’ Comprehensive Permit Law, Chapter 40B, which was enacted to address the shortage of affordable housing statewide. Overlook the unwieldy title and you’ll find a fairly simple mandate: reduce unnecessary barriers created by local approval processes, local zoning and other restrictions to encourage the production of affordable housing throughout the Commonwealth.

The Bay State statute enables local zoning boards to approve affordable housing developments under flexible rules if at least at least 20 percent of the units are considered affordable for rental, or 25 percent are affordable for home ownership.

When a developer puts forth a proposal, he or she can potentially bypass much of the normal local governmental approval process. The project’s application goes into a streamlined approval process with fewer requirements and the developer has the right to appeal an adverse local decision to the state in communities with little affordable housing (less than 10 percent of their year-round housing).

Since 1969, Chapter 40B has been responsible for the production of affordable housing developments that in most cases could not have been built under traditional zoning approaches. As one report notes, these include “church-sponsored housing for the elderly, single-family subdivisions that include affordable units for town residents, multifamily rental housing developments and mixed-income condominium or townhouse developments.”

According to Galante, California’s local governments currently hold neither a carrot nor a stick to build such housing. Although she thinks some form of the Massachusetts law would help many Californians find affordable homes, she understands the barriers.

“That’s politically a very hard sell for California to come in and, legislatively, do that,” she said. “It’s not an easy political thing.” City governments, legislators, homeowners and market-rate housing developers would likely come out howling in objection over a similar proposed law.

Educating California residents and convincing them that housing is a problem is the first step to solving this crisis and getting more homes built, said Cathy Creswell, the former acting director of the California Department of Housing and Community Development. She is currently the Housing Action Team Co-Lead for the California Economic Summit, a multiyear partnership between the politically powerful California Forward and the California Stewardship Network.

At their annual meeting held late last year, about 400 civic and business leaders from across the state came together to discuss a vision for California’s future. A main focus was housing and the group came up with a goal for 2016: to support policies that will help build one million more homes over the next decade.

“In terms of the volume of need, if anything, it may be a little low just because we have this pent-up demand which hasn’t been met in the last decade,” said Creswell. “The idea was that building these new homes not be so far out of reach that it couldn’t happen.”

She said the state needs to get serious about providing the financing that is necessary and addressing the market, and believes every resident, even those who live in comfortable homes in nice communities, have a vested interest in addressing the complex problem.

“I think we need to be so out of the box that we should be willing to look at anything,” said Creswell, who wonders if the tiny house movement can become another vehicle to provide more housing. After all, building second units on one lot or adding granny units to homes is not a new concept.

“Right now [tiny houses] seem to be very hip,” Creswell said. “The perception is that [they’re] for the new young professional urban dwellers.”

Many of them are very expensive but built as a kit, meaning they can be much cheaper than a conventional single family home and could potentially provide an option for people who want home ownership without the hefty price tag.

But Creswell knows that finding communities willing to accept zoning changes to allow neighborhoods of tiny homes would be a hurdle. This is housing that doesn’t sit with existing development standards, Creswell said. And people typically don’t like things that are different.

“People shouldn’t be afraid of having an affordable home next to them,” Creswell said. “After all, that could be housing for their kid’s teacher.

Matt Schwartz, president and chief executive officer of the California Housing Partnership, is another advocate who was disappointed in Governor Brown’s veto of raising the annual low-income housing tax credit – as well as by inaction on the affordable housing issue.

He believes Brown has been a barrier to progress on this issue and says the governor seems to care about only three things: high-speed rail, the drought and climate change. Brown, who otherwise has a good record on progressive issues, has been lax in doling out more state funds for affordable housing, Schwartz and others complain.

“The state can’t afford any more investments, they say,” according to Schwartz. “Or they will bring up how they passed the earned income credit for poor people, which puts a few more hundred dollars in their pockets every year – but that’s not even close enough to help them afford housing. Study after study shows that the number one factor [in] addressing persistent poverty is access to stable, affordable housing.”

Schwartz is also a big fan of the Massachusetts mandate and wonders if something similar can be fashioned in this state.

“This program has been deemed a success nationally, so why can’t California do it?”

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy

-

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024Critical Audit of California’s Efforts to Reduce Homelessness Has Silver Linings

-

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024Nurses Union Says State Watchdog Does Not Adequately Investigate Staffing Crisis

-

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024Economist Michael Reich on Why California Fast-Food Wages Can Rise Without Job Losses and Higher Prices

-

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024

California UncoveredApril 19, 2024Los Angeles’ Black Churches Join National Effort to Support Dementia Patients and Their Families

-

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024In Georgia, a Basic Income Program’s Success With Black Women Adds to Growing National Interest

-

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024Report: Banks Should Set Stricter Climate Goals for Agriculture Clients

-

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024Unionizing Planned Parenthood