Culture & Media

Interview With the Director of ‘Following the Ninth’

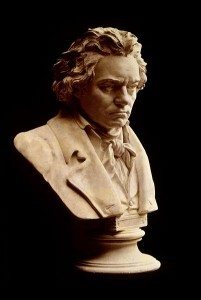

Author and documentary film co-producer (Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price, Iraq for Sale) Kerry Candaele’s newest work records the transformative power that Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony has had upon the lives of four people. These stories took him to a dozen countries on five continents, part of a journey of discovery about one of music’s greatest achievements. In Candaele’s new documentary, Following the Ninth: In the Footsteps of Beethoven’s Final Symphony, the Ninth’s “Ode to Joy” choral finale emerges as a soundtrack for social justice and world brotherhood.

In this film, which Bill Moyers calls “beautiful and powerful,” Candaele recounts the struggles of rebellious students like Feng Congde at Tiananmen Square, who played the “Ode to Joy” over loudspeakers as they faced the tanks, and women activists like Isabel Lipthay, who sang it outside the torture prisons in Pinochet’s Chile. Candaele highlights the jubilation as the Berlin Wall came down through the poignant story of Lene Ford, who joined the festivities as Leonard Bernstein conducted the Ninth at the Brandenburg Gate. Finally, he visits Japan where he meets Akira Takauchi, who sings as part of a chorus that takes the Ninth to Fukushima after its devastation by the earthquake and tsunami. I caught up with Candaele as he arrived in town for the film’s Friday Los Angeles premiere.

Frying Pan News: What was the impetus for your pursuing this project?

Kerry Candaele: It was the Ninth itself. I was raised on rock, the standard fare — the Beatles, Dylan, the Stones — so I can say [Beethoven’s] music truly changed my life. And once I’d discovered it, I kept coming across the Ninth. Like Billy Bragg rewriting the libretto for the symphony.

FPN: Interestingly, the Beatles used a part of the Ninth in their film Help! And it’s the European Union’s anthem.

Candaele: Exactly, it’s everywhere and all around us, for better and for worse sometimes. “Ode to Joy” is used in Die Hard 3, I believe.

FPN: Do you think that its status as the first choral symphony ever written is one reason it resonates with so many popular movements? All those voices in unison, which perhaps suggests Beethoven’s own longings for universal brotherhood?

Candaele: Yes, it’s about people singing together, working together and often that musical connection is transcendent, in the best of ways. I think it’s a symphony of great hope. And what else is there? You have to err on the side of hope. Beethoven’s politics were complicated and I think he struggled in writing the symphony with his youthful radicalism, his support of the French Revolution at a time when, as William Wordsworth put it, “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven.” The Ninth is taking another look, another pass, at [Beethoven’s] youthful radicalism. And of course he lived under a repressive Austrian regime at the time. On his best days Beethoven believed in mankind, but he believed in himself and his art even more.

FPN: How did you find the four subjects for your film?

Candaele: I was reading an article by Ariel Dorfman about Chile during the Pinochet years and the repression there. I contacted him and that led me eventually to Isabel and her incredibly inspiring story. Feng was working in New York City for a human rights organization and I found Lene Ford through Craigslist. Her story was so compelling—her spirit and joy, how she had lost someone who’d tried to escape across the wall just months before the wall came down. I got connected to Akira through someone I met in Santa Barbara and was amazed to see the conductor of his orchestra turn to conduct the audience in singing the “Ode to Joy.” I’d never seen that before, that kind of inclusion. Very Japanese. Dudamel has that inclusiveness, but I’ve never seen him turn and actually conduct the audience!

The episodes in the film are utopian moments – not blueprints – for a good society and these utopian moments live on in people and in movements. They sometimes change over time, speak in a different voice, but they almost always return. This is why I was interested in the four stories I chose from Japan, East Germany, Chile and China.

FPN: And the Japanese story is different in that it is not about a social or political struggle, but rather about a society’s response to a natural disaster.

Candaele: Yes, it’s very personal, about the song’s power to heal people, to repair them and help them rebuild society together. Akira and others talk about the Ninth living within their bodies. Music changes lives. Many believe the Ninth is the greatest symphony ever written and it’s certainly one of the most popular. These facts made it hugely challenging to work with. I didn’t want to make it too polemical, overtly political or agitprop. I wanted to make a human film that most people could identify with.

FPN: And music is the universal language. What is it about the Ninth symphony that affects people in such a powerful and unique way?

Candaele: The great English socialist writer, William Morris, talked about teaching “desire to desire, to desire better.” In other words, we often don’t really know what we want, we don’t know how to desire a more brotherly/sisterly existence until we find it, where we are then confronted with our limitations. Feng discovered this when he went to Tiananmen Square because his computer was broken. He was actually planning on going overseas to study at that time. But once he got to Tiananmen, he never left once he connected to what was happening there. If you listen to the Ninth symphony all the way through and experience the struggle, the longing, the moments of melancholy and then finally reach the “Ode to Joy,” something happens that happened to Feng—that is what William Morris perhaps was talking about. You have to experience the pain, the melancholy, the longing in order to get to the joy and freedom. They are all linked and inseparable.

FPN: What is your greatest hope for this film?

Candaele: People came out of the theater in New York crying – I want everyone to have that kind of profound experience. Music knows no boundaries. As Feng described the students who gathered at Tiananmen Square, they all spoke the same language, but before they met on the square no one could hear each other. In the Ninth, humanity speaks as one.

(Opens Friday, November 22. Laemmle’s Music Hall, 9036 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills (310) 478-3836.)

See also: Bill Moyers interviews Kerry Candaele.

-

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024Tried as an Adult at 16: California’s Laws Have Changed but Angelo Vasquez’s Sentence Has Not

-

Latest NewsApril 17, 2024

Latest NewsApril 17, 2024Despite Promises of Transparency, California Justice Department Keeps Probe into L.A. County Sheriff’s Department Under Wraps

-

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024‘Every Day the Ocean Is Eating Away at the Land’

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy

-

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024Critical Audit of California’s Efforts to Reduce Homelessness Has Silver Linings

-

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024Nurses Union Says State Watchdog Does Not Adequately Investigate Staffing Crisis

-

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024Economist Michael Reich on Why California Fast-Food Wages Can Rise Without Job Losses and Higher Prices

-

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024In Georgia, a Basic Income Program’s Success With Black Women Adds to Growing National Interest