Culture & Media

Ava DuVernay’s “13th” Amendment Documentary Packs a Wallop

After Ava DuVernay burst into the mainstream as director of the acclaimed 2014 film Selma, she did not earn an Academy Award nomination for Direction, despite the film earning a Best Picture nod. Whatever doubts anybody might have had about her skill as a director should now be put to rest after her stunning new documentary 13th, now streaming on Netflix.

After Ava DuVernay burst into the mainstream as director of the acclaimed 2014 film Selma, she did not earn an Academy Award nomination for Direction, despite the film earning a Best Picture nod. And while she is hardly the first filmmaker to endure such an oversight, some made the case that she was a victim of Hollywood profiling. After all, it’s doubly hard to be a black woman in Tinseltown, or in many places in this country, for that matter. Whatever doubts anybody might have had about her skill as a director should now be put to rest after her stunning new documentary 13th (now streaming on Netflix).

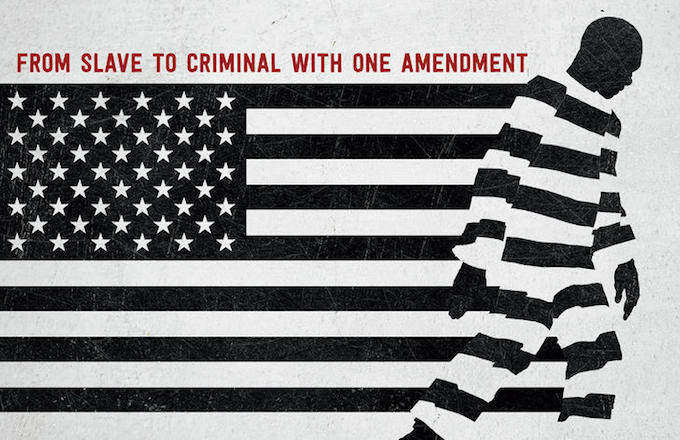

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The premise that this one line in the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution has sanctioned systemic racism in this country doesn’t seem like a riveting proposition for a feature documentary. The scourge of discrimination is not a new subject, and recent events have made it a hot topic explored in just about every medium. But that makes DuVernay’s achievement that much more impressive. From its first moments, 13th grabs the viewer by the jugular and doesn’t let go – and by the final credits it’s hard to not be awestruck by DuVernay’s supreme talent.

The film’s core message is a simple yet disarming one: That ever since Africans were brought over as slaves they have, in effect, remained slaves to this day. The abolition of slavery was merely replaced by other systems that have kept a whole population enslaved (lynching, Jim Crow laws, the War on Drugs, Bill Clinton’s Violent Crime Control Act and its three-strikes provisions) — culminating with the modern for-profit prisons that perpetuate it by adding a profit motive to mass incarceration.

The film uses customary documentary elements: graphics to illustrate the increasing population of our prisons over the decades, music to provide pop-culture commentary from the street, and talking heads to discuss the reasons behind the obscene percentage of African Americans behind bars. But what DuVernay and editor Spencer Averick (who co-wrote the film with the director) do with this material is anything but ordinary. The film quickly accelerates to a breakneck pace, but still manages to keep the storytelling robust and revelatory. The staccato bursts of fresh and enlightening information make it seem as if the filmmakers have invented a different filmic language entirely.

Across generations, everyone from scholars to social commentators to activists offer opinions on the subject, and while there is certainly a grab bag of go-to liberals (Henry Louis Gates, Angela Davis, Van Jones), there are a few voices from the other side (such as Newt Gingrich) presented in an attempt to lend some balance. The best of them might be attorney/author Bryan Stevenson, who sums up the film by noting, “People say all the time, ‘I don’t understand how people could have tolerated slavery.’ ‘How could people have gone to a lynching and participated in that?’ ‘How did people make sense of segregation?’…’That’s so crazy! If I were living at that time I would never have tolerated anything like that.’ And the truth is, we are living at this time and we are tolerating it.” Observations like that, or a new filmic juxtaposition, happen every few moments, and they nearly take one’s breath away.

After a 90-minute onslaught to the senses and synapses, DuVernay brings the film to a stunning climax. She crafts a montage of footage of recent police-on-black shootings, much of which recently has been seared into our nation’s consciousness. The images, strung out collectively, stun in a way that is unexpectedly potent and heartbreaking. DuVernay punctuates each of these clips with a graphic that says that it is being shown with the permission of the victim’s family. By employing this seemingly unnecessary addition in this way, DuVernay makes it suddenly appear completely necessary — as a graceful way for these victims and their loved ones to reclaim some of their dignity that was so publicly stripped from them. It is an elegant ending to an elegiac and essential film. Made, most assuredly, by a masterful director.

-

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024700,000 Undocumented Californians Recently Became Eligible for Medi-Cal. Many May Be Afraid to Sign Up.

-

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024Regional U.S. Banks Sharply Expand Lending to Oil and Gas Projects

-

Class WarMarch 26, 2024

Class WarMarch 26, 2024‘They Don’t Want to Teach Black History’

-

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024The Transatlantic Battle to Stop Methane Gas Exports From South Texas

-

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024A Whole-Person Approach to Combating Homelessness

-

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 27, 2024Street Artists Say Graffiti on Abandoned L.A. High-Rises Is Disruptive, Divisive Art

-

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024

State of InequalityApril 11, 2024Dispelling the Stereotypes About California’s Low-Wage Workers

-

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024

Latest NewsApril 24, 2024An Author Reflects on the Effort to Rebuild L.A. After the ‘Violent Spring’ of 1992