Labor & Economy

A Plague of Profits?

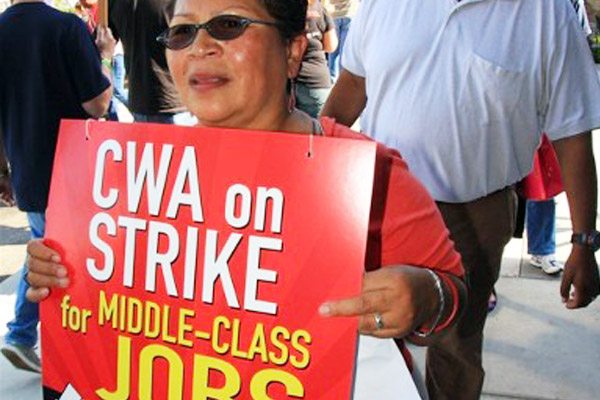

Photo: Slobodan Dimitrov

A few years ago the nonprofit, nonpartisan Los Angeles Economic Roundtable released a study that got too little attention. It found that union workers in the county earn 27 percent more than nonunion workers in the same jobs. These extra wages for the 800,000 union workers—17 percent of the labor force—added $7.2 billion a year in pay. As union workers spent their wages on food, clothing and other items, their additional buying power created 64,800 jobs and $11 billion in economic output. Let me repeat: $11 billion.

Clearly unions are good for the economy. But to hear business propaganda tell it, that 11 billion is the 11th Plague, because anything that moves the country away from an imaginary, 19th-century Utopia where business held all the cards, is to be avoided — like the plague.

This winner-take-all crowd should be happy because, in many ways, America today does resemble its Gilded Age of the late 1800s — an era of rampant, unregulated capitalism, merger mania and the rise of the Robber Barons. During that period new technologies made possible new industries, which generated great riches for the fortunate few, but at the expense of workers, consumers, and the environment. The gap between the rich and other Americans yawned chasm-like.

Jump to 2010, when the CEOs of America’s biggest corporations got a cool 23 percent raise and corporate profits surfed at record highs. In its July 11 “Eye on the Market” newspaper, JPMorgan bloodlessly described how this was possible during a deep recession:

“Reductions in wages and benefits explain the majority of the net improvement in [profit] margins . . . U.S. labor compensation is now at a 50-year low relative to both company sales and U.S. GDP.”

That’s one way of putting it. Another, in plain English, is that most Americans have too little money to spend. Businesses are making money, but they aren’t hiring, because consumer demand is as anemic as JPMorgan’s prose – thanks to 15 million people being out of work. The share of unemployed workers who had been jobless for more than six months has shot up to over 45 percent, an all-time record. About another 9 million Americans want full-time jobs but have had to settle for part-time work. And, as the JPMorgan report indicated, those who are working are earning less than they did before the recession.

The current gap between the rich and everyone else stretches wider now than at any time since the stock market crash of 1929. The way to bridge this distance is to put more money in the pockets of ordinary American workers and their families. The breathtaking prosperity of the post-World War II era was largely due to increased wages and resulting consumer demand. From the late 1940s through the early 1970s, U.S. incomes at the bottom two-thirds of the class structure rose faster than those at the top – pulling up the Gross National Product and the standard of living with them.

This didn’t happen by accident. Government initiatives (a massive national highway-building program, huge subsidies and financial aid to expand the college and university system, federal insurance to increase home ownership) and a large defense budget boosted employment and stimulated consumer demand – all of which just also happened to provide America’s businesses with record profits.

A key ingredient in this post-war prosperity was the growing influence of labor unions — by the late 1950s one-third of America’s workforce belonged to one. The labor movement didn’t just lift some Americans into the middle class – it practically created the modern middle class. According to the Economic Policy Institute, union workers earn 14.1 percent more in wages than nonunion workers in the same occupations and with the same level of experience and education. This “union premium” is considerably higher when total compensation is included, because unionized workers are much more likely to get health insurance and pension benefits.

Compare two newly hired, similarly educated security guards who work in large downtown Los Angeles buildings for Securitas, the nation’s largest security company, with $8.7 billion in revenues last year. Jose’s starting pay is $11.50 an hour with paid health insurance, as well as two sick days, five paid holidays, five vacation days (increasing to 10 days after five years), three paid bereavement days, and a daily uniform maintenance allowance of $2. Bill, on the other hand, starts at $8 an hour (the state minimum wage) and gets no health insurance or any other benefits.

Why the difference? Jose is a member of the Service Employees International Union, which has a collective-bargaining agreement with Securitas, while Bill is on his own, with no union contract.

This raises another point: Unions not only lift wages; they also reduce workplace inequalities based on race. The union wage premium is especially high for black employees (18.3 percent), Hispanic employees (21.9 percent), and Asian employees (17.4 percent). (The union wage premium is 12.4 percent for white employees.) Unions help to close racial wage gaps by making it tougher for employers to discriminate.

Likewise, unions reduce workplace inequalities based on gender. The union wage premium is 14.5 percent for black women, 18.7 percent for Hispanic women, 12.6 percent for Asian women, and 9.1 percent for white women. Unions also reduce overall wage inequalities, because they raise wages more at the bottom and middle than at the top.

Unions put money in the pockets of average Americans. When they spend it, businesses expand, invest, and hire more people, and the overall economy improves. Forget the scare talk of plagues. Stronger unions make a stronger economy and a stronger America.

-

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024

Latest NewsApril 3, 2024Tried as an Adult at 16: California’s Laws Have Changed but Angelo Vasquez’s Sentence Has Not

-

Latest NewsApril 17, 2024

Latest NewsApril 17, 2024Despite Promises of Transparency, California Justice Department Keeps Probe into L.A. County Sheriff’s Department Under Wraps

-

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 20, 2024‘Every Day the Ocean Is Eating Away at the Land’

-

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024

State of InequalityApril 4, 2024No, the New Minimum Wage Won’t Wreck the Fast Food Industry or the Economy

-

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024

State of InequalityApril 18, 2024Critical Audit of California’s Efforts to Reduce Homelessness Has Silver Linings

-

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024

State of InequalityMarch 21, 2024Nurses Union Says State Watchdog Does Not Adequately Investigate Staffing Crisis

-

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024

Latest NewsApril 5, 2024Economist Michael Reich on Why California Fast-Food Wages Can Rise Without Job Losses and Higher Prices

-

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024

Latest NewsMarch 22, 2024In Georgia, a Basic Income Program’s Success With Black Women Adds to Growing National Interest