Culture & Media

A March Into History

Fifty years ago, just a year out of high school, I sat in my parents’ small living room engrossed by images on the flickering black and white TV screen. Something called the March on Washington was running live — the whole event, as I recall, which network television did in those days. I’m not sure why I was not at work or why I was alone in the house, but I remember that tears came to my eyes, just as they do now as I think back on that day.

My parents were originally from the South, but both grew up in Southern California. My mother had been born in Mississippi, moved to Texas and then Inglewood. My father came from Texas to La Crescenta. After they married and my father became a minister, Northern California was home, but the ethos of white superiority and other ethnic and class inferiorities were engrained. Not in so many words, but in “looks” and sometimes in references. No one used the N-word in our household, but then, no one used any four-letter slang words either. It wasn’t allowed.

Occasionally I would ask about things I found in my high school history textbook: about the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, or why Negro people couldn’t vote in the South. Once, my mother gave me her high school history book, which carried a white, Southern narrative about the post-Civil War era, and since this version of history came from my mother and in a book, I thought it must be true. These were rare interactions in my family, because mostly the subject of race was never mentioned. Much more than verbalized, our racial attitudes were modeled.

So I was not consciously taught to be a racist, but I am white and was raised on the white side of a small agricultural town in the Central Valley, at the lower edge of middle class. The black high school was across town. The poor whites and people of other ethnicities – in those days mainly Mexican, Filipino, Chinese – went to yet another school on the east side. Occasionally we had some minimal interaction — a debate tournament or a football game, not much.

There were areas of the city we did not visit. When we did, the poverty and the living conditions were subtly disdained by my parents, as if these older areas of town had something to do with the moral temperament of the people who lived in them. My father knew people in some of those neighborhoods, but we seldom went there. The official “ministerial association” included only white, middle class clergy, although there were ministers and churches in the city that served those other communities.

Then, too, there were the usual slurs and references – embarrassing to think about today – that occasionally passed through our conversations as white kids in high school. Not pervasive, just regular demeaning phrases, and no one thought twice about it. A common and relatively benign one was, “I’m free, white and 21” – which of course, as teenagers locked into a school system and dependent on our parents, we were not. Yet it characterizes an arrogance that was opaque to us and to which most majority Americans are blind even now.

No, we weren’t trained to be racists. We inhaled prejudice like the air we breathed. It was invisible. It was inscribed. It was embedded. It was unconscious.

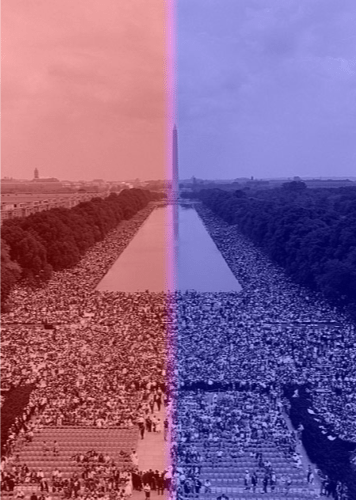

Except on that day 50 Augusts ago, as I sat before a television watching the National Mall fill with people, both black and white. I saw that event from beginning to end and, hearing those words call out for us to be better as a people than we were, something new came into my heart. People spoke, some whose names were slightly familiar, others who were not. Then Martin Luther King Jr. came to the microphone. As he delivered his cadenced poem of a dream, my eyes spilled over and the tears ran down my cheeks. To the organizers of the March on Washington, it was a call for legislation that roused the nation to adopt the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. For me – and I think for many of my generation – that day was a march into my soul. King’s dream became my imperative.

-

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024

Latest NewsApril 8, 2024Report: Banks Should Set Stricter Climate Goals for Agriculture Clients

-

Latest NewsApril 22, 2024

Latest NewsApril 22, 2024Oil Companies Must Set Aside More Money to Plug Wells, a New Rule Says. But It Won’t Be Enough.

-

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024

Striking BackMarch 25, 2024Unionizing Planned Parenthood

-

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024

California UncoveredApril 9, 2024700,000 Undocumented Californians Recently Became Eligible for Medi-Cal. Many May Be Afraid to Sign Up.

-

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024

Feet to the FireApril 22, 2024Regional U.S. Banks Sharply Expand Lending to Oil and Gas Projects

-

Class WarMarch 26, 2024

Class WarMarch 26, 2024‘They Don’t Want to Teach Black History’

-

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024

Latest NewsApril 10, 2024The Transatlantic Battle to Stop Methane Gas Exports From South Texas

-

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024

Latest NewsApril 23, 2024A Whole-Person Approach to Combating Homelessness